Determine the location of the fistula in relation to the vaginal apex and bladder trigone and assess the quality of surrounding tissue (eg, presence of inflammation, edema, or infection). Fistulas near the vaginal apex may require a more complicated abdominal approach, and those close to the trigone may be associated with increased risk of ureteral injury during repair.

If the fistula is particularly small, no tract may be apparent. In such cases, bimanual exam with careful palpation of the anterior wall may help isolate the fistula (eg, when there is a surrounding zone of induration).

Office tests. If no fistula is noted despite highly suspicious signs and symptoms and careful examination, a simple office test can be performed. Using a catheter, fill the bladder with a dyed solution such as normal saline with indigo carmine and repeat the pelvic exam with a half-speculum to visualize the anterior wall. Ask the patient to cough and bear down, and identify the fistula by visualizing urine leakage.

If this test fails to locate the fistula, insert a tampon and ask the patient to perform 10 to 15 minutes of exertional maneuvers, including stair climbing and jumping in place. Then remove the tampon. Visualization of dye beyond the most distal edge of the tampon confirms the presence of a fistula.

A variation of this technique is the double-dye test: Give the patient oral phenazopyridine (Pyridium), fill the bladder with the blue-tinted solution, and insert a tampon. The presence of blue staining suggests vesicovaginal or urethrovaginal fistula, while red staining (Pyridium) suggests ureterovaginal fistula.

Other testing. Further assessment is recommended to rule out concurrent pathology and formulate an appropriate treatment plan. Routine testing should include a urinalysis and culture to exclude coexisting urinary tract infection, an electrolyte panel to evaluate renal function, and a complete blood cell count to rule out systemic infection.

Cystoscopy should be performed to visualize the fistulous tract, assess its location in relation to the ureters and trigone, assure bilateral ureteral patency, and exclude the presence of a foreign body or suture in the bladder.

In patients with a history of urogenital malignancy, biopsy of the fistula tract and urine cytology is warranted.

Comparable success rates have been reported for early and late repair of surgery-induced fistulae.

Radiologic studies are recommended prior to surgical repair of a vesicovaginal fistula to fully assess the defect and exclude the presence of multiple fistulae. An intravenous pyelogram is helpful to exclude concurrent ureterovaginal fistulae or ureteral obstruction. A targeted fistulogram may be indicated if conservative therapy is planned, including expectant management, continuous bladder drainage, fulguration, or fibrin occlusion.

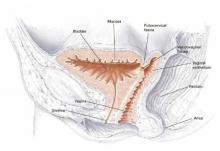

FIGURE 1 Vesicovaginal fistula

Pelvic cross section depicting high vesicovaginal fistula.TABLE

Classification of vesicovaginal fistulae17

| CLASSIFICATION | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Simple |

|

| Complicated |

|

Indications for conservative management

Because spontaneous closure is uncommon, symptomatic VVF merits treatment. Appropriate therapy depends on various factors, including fistula size and location, timing from the antecedent event, severity of symptoms, quality of surrounding tissue, and clinician experience and surgical skills.

Occasionally, a fistula heals following prolonged bladder drainage through a transurethral or suprapubic catheter—provided it is diagnosed within a few days of surgery. Zimmern5 recommends a conservative approach to small fistulae if the patient’s complaints of urinary incontinence are resolved with insertion of a Foley catheter. In this case, bladder drainage should be continued for 3 weeks, followed by reevaluation of the fistula. If the fistula has diminished in size, an additional 3 weeks of catheter drainage is associated with a high rate of spontaneous closure; if there is no change, the fistula is unlikely to resolve spontaneously.5

Varying success rates have been reported for conservative management, ranging from 2% to 80%.4,6 The chances of success are apparently greater if the fistula is:

- diagnosed within 7 days of the index surgery,

- less than 1 cm in size,

- simple, without associated carcinoma or radiation, and

- subject to at least 4 weeks of constant bladder drainage.

Persistent, large, or complex fistulae are best treated surgically.

Indications for surgical management

The basic principles of fistula closure apply. They are:

- adequate exposure,

- good hemostasis,

- wide mobilization of the bladder and vagina,

- resection of devascularized tissue,

- removal of any foreign bodies,

- tension-free closure,

- nonopposition of suture lines,

- confirmation of a water-tight seal on bladder closure, and

- bladder drainage for 10 to 14 days following the repair.