I strongly believe that identifying the ureter during any dissection that endangers it is the best way to avoid injury. Even after these precautions, I frequently perform cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine to confirm ureteral patency. This is my standard approach with all vaginal procedures, as I am not confident that I can palpate the course of the ureter.

Postoperative cystoscopy is virtually without morbidity and adds no more than 3 minutes to the procedure when properly planned. It also affords an excellent opportunity to train residents in cystoscopy.

How to assess patency after selected procedures

BENT: Ureteral patency should be assured after any repair of the pelvic floor.

After abdominal hysterectomy, if there is blood in the catheter bag or any difficulty has been encountered during surgery, I perform cystoscopy after injecting indigo carmine dye, to observe ureteral function.

At abdominal or laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, I follow the path of the ureters over the pelvic brim and inferiorly to the adnexal area by direct inspection.

During abdominal or laparoscopic paravaginal repair, the Burch procedure, or uterosacral ligament suspension, I perform cystoscopy after tying sutures and injecting indigo carmine to ensure ureteral function.

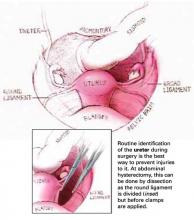

To safeguard the ureter, follow its course

Vaginal hysterectomy is not usually associated with ureteral injury, and very uncommonly with bladder injury. However, if bladder injury is observed or the procedure has been difficult, it is wise to perform cystoscopy with dye injection. This also extends to traditional cystocele repair.

I also recommend cystoscopy with dye injection any time there is a vaginal approach to paravaginal defect repair, vault suspension, or colpocleisis.

Cystoscopy—safe, simple, and efficient

KARRAM: For vaginal surgery, I think cystoscopy is the simplest way to assess the lower urinary tract. I routinely use it after any procedures involving the posterior cul-de-sac such as McCall culdoplasty or vaginal vault suspension from the uterosacral ligaments. I also use it routinely after advanced prolapse repairs involving anterior colporrhaphy, as well as paravaginal defect repairs, and I certainly use it routinely after any lower urinary tract reconstructive procedures such as fistula repairs.

As for laparoscopic surgery, I think cystoscopy is again the most efficient way to assess the lower urinary tract. I do so after any retropubic suspension, be it a Burch colposuspension or a paravaginal repair, any type of vault suspension or sacrocolpopexy, and any type of hysterectomy or adnexectomy that involves dissection of the retroperitoneal space. I also do so if an energy source was used extensively in the vicinity of the retroperitoneal space on either side.

After abdominal surgery, it is probably more efficient (assuming the patient is not in stirrups) to perform a high extraperitoneal cystotomy or suprapubic telescopy. The indications are any difficult dissection in which I have concerns about ureteral patency, as well as any abdominal prolapse or anti-incontinence procedures.

Ureteral stenting

Is ureteral stenting ever indicated preoperatively? If so, when?

BARBER: I do not think ureteral stenting is indicated routinely for any procedure. There may be individual cases where a stent may help the surgeon avoid ureteral injury, but I can’t think of a procedure in which it should be routinely used.

CUNDIFF: I agree. Although ureteral stenting is an important tool for the pelvic floor surgeon to investigate potential ureteral obstruction, I think it has very limited value as a preoperative maneuver to avoid injury. My opinion is based on the following observations:

The surgeon cannot really assess the potential difficulty of identifying the course of the ureter until the peritoneal cavity is entered.

For the truly hostile pelvis, in which pelvic sidewall pathology prevents identification of the course of the ureter, I do not find that a stent facilitates dissection of the pararectal space and ureterolysis. In fact, it could increase the chance of ureteral injury by creating a backboard against which to cut it during dissection.

Any potential benefit of ureteral stents—which I believe is minimal—must be balanced against the potential risks, which include 20 to 30 minutes of added OR time and the risk of ureteral spasm or perforation.

BENT: I also agree that ureteral stenting is seldom helpful during gynecologic surgery. At laparotomy, direct dissection of the structures and exposure of the ureter are best; there is no need to feel for a ureter.

At laparoscopy, however, if there are large fibroids, scarring from endometriomas, or adnexal masses, then preoperative placement of lighted stents can help the surgeon identify the ureters during dissection. The case would still require dissection of the ureter away from the operative field, but the lighted path provides a starting point in this procedure.