Vaginal techniques

Proponents of the vaginal approach argue that, by avoiding the need for laparotomy, it results in fewer complications, less blood loss and postoperative discomfort, a shorter hospital stay, and less expense.5

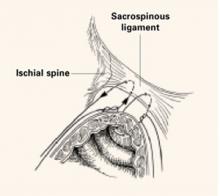

Sacrospinous ligament fixation

The sacrospinous ligaments extend from the ischial spines on either side to the lower portion of the sacrum and coccyx. Fixation of the vaginal apex to 1 or both of the sacrospinous ligaments is an option for posthysterectomy vault prolapse.

Technique. Nichols6 described the need to penetrate the right rectal pillar into the pararectal space near the ischial spine. The next step is grasping the ligament and muscle with a long Babcock clamp. Place two #2 polyglycolic sutures through the sacrospinous ligament, 1.5 to 2 fingerbreadths medial to the ischial spine. Attach 1 end of the suture to the undersurface of the posterior vaginal wall at the apical area. When the posterior colporrhaphy reaches the midportion of the vagina, tie the sacrospinous suspension sutures, firmly attaching the vaginal apex to the surface of the coccygeal-sacrospinous ligament complex with no intervening suture bridge (FIGURE 1).

Modifications. The most notable modification is the Miyazaki technique, which substitutes the Miya hook for the DesChamps ligature carrier. The Miya hook is reportedly safer for the pudendal complex, which may lie up to 5.5 cm medial to the ischial spine.7 The path of the Miya hook avoids Alcock’s canal and its neurovascular pudendal bundle.

The Caprio ligature carrier (Boston Scientific, Boston, Mass) is also useful for the placement of sacrospinous sutures; unlike the Miya hook, however, the Caprio ligature carrier is a disposable instrument and thus is not reusable.

Potential complications of sacrospinous ligament fixation include hemorrhage, pudendal nerve injury, rectal or bladder injury, and recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

Outcomes. Follow-up studies in women undergoing this procedure report a roughly 20% incidence of recurrent or persistent anterior vaginal wall relaxation, or symptomatic cystocele, within 1 year after the surgery. Alteration of the vaginal axis in an exaggerated posterolateral direction after this procedure is thought to place undue tension on the anterior segment of the vaginal wall and predispose women to prolapse at a site opposite the repair.8,9

FIGURE 1 2 “pulley stitches” secure the apex

Place 2 nonabsorbable monofilament “pulley stitches” to secure the vaginal apex to the ligament.

Iliococcygeal fixation

Inmon10 was the first to describe a technique in which the everted vaginal apex is secured to the iliococcygeal fascia bilaterally, just below the ischial spine. He performed this technique successfully in 3 women with atrophied uterosacral ligaments.

Technique. Open the posterior vaginal wall in the midline, as if preparing to perform a posterior colporrhaphy. Develop the rectovaginal spaces bluntly and bilaterally—laterally toward the levator muscles and posteriorally toward the ischial spines. Use the nondominant hand to depress the rectum downward and medially, and place a single #0 polyglycolic suture deep into the iliococcygeus muscle and fascia at a point 1 to 2 cm caudad and posterior to the ischial spine. Then pass both ends of the suture through the ipsilateral posterior vaginal apex and hold them with a hemostat. Repeat the procedure contralaterally.

Usually no vaginal epithelium needs excision because the upper vagina is attached bilaterally, resulting in good vaginal length and circumference. When posterior colporrhaphy is completed and the posterior vaginal wall is closed, tie both iliococcygeal-fixation sutures in place.

Complications. Shull and colleagues11 studied 42 women who underwent suspension of the vaginal cuff to iliococcygeus fascia and repair of coexisting pelvic support defects. Of these women, 2 (5%) had recurrence of their cuff prolapse during follow-up, one of whom required further surgery (she also had recurrence of an inguinal hernia that had been repaired at the original surgery). The other patient, who had undergone 5 previous pelvic procedures, developed asymptomatic prolapse of the cuff halfway to the hymen. Six additional patients had loss of support at other sites in the follow-up period, one of whom required repeat surgery. Ninety-five percent of women experienced no persistence or recurrence of cuff prolapse 6 weeks to 5 years after the procedure.

Meeks and colleagues12 also applied the Inmon technique in 110 women with posthysterectomy vault prolapse or total uterine procidentia. In both studies, the most commonly reported complications included hemorrhage (1.2%), bladder/rectal perforation (1.2%), and recurrent vault prolapse (8%).

Benefits. In comparison with sacrospinous ligament fixation, iliococcygeus fixation is technically easier and places less tension on the anterior vaginal wall.

Modified McCall culdoplasty

Symmonds and colleagues13 described this approach to symptomatic vaginal vault prolapse.

Technique. Excise an elliptical wedge of mucosa from the anterior and posterior walls of the prolapsed vagina to narrow the vault and allow access to the lateral fascial supports of the vagina and rectum. The width and length of the excised wedges are determined by the desired dimensions of the reconstructed vagina.