How pregnancy affects asthma

Pre-pregnancy severity is key

Asthma improves in approximately one third of women, remains the same in one third, and worsens in one third. The severity of asthma prior to pregnancy correlates with the response of asthma to the pregnancy. The more severe the asthma before pregnancy, the more likely severity will increase during pregnancy.3

In rare cases, asthma presents for the first time during pregnancy.

Subsequent pregnancies are similarly affected. The changes in severity that occur in 1 pregnancy tend to recur in subsequent pregnancies.4

Some gestational ages are more problematic. The first trimester is generally well tolerated by women with asthma, with rare exacerbations. When symptoms increase, it tends to be near the start of the second trimester until about 36 weeks. Acute exacerbations are most frequent at 26 weeks.

Asthma problems are fewer and less severe during the last 4 weeks of pregnancy, even among women whose disease has worsened over the pregnancy.

Symptoms during labor and delivery are usually mild and easily controlled

Only 10% of women with well-controlled asthma experience increased symptoms during labor and delivery, and these symptoms are usually mild and easily managed. In a study of 360 patients,4 37 women were symptomatic during labor and delivery. Of these, 54% required no treatment, 15% used inhaled bronchodilators, and 5% were given intravenous (IV) aminophylline.

An 18-fold increased risk of asthma exacerbation during delivery by cesarean section was reported in another study, compared with vaginal delivery.5

Quick return to pre-pregnancy function. After delivery, most women promptly return to pre-pregnancy pulmonary function.

How asthma affects pregnancy

Prospective and retrospective studies confirm that severe or uncontrolled disease during pregnancy may result in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Maternal complications include preeclampsia (risk increases 2- to 3-fold6), gestational diabetes, preterm labor, vaginal hemorrhage, placenta previa, toxemia, and cesarean delivery.7-9 A study of 24,115 women with no history of chronic hypertension found a significant association between asthma (needing treatment) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (P<.001).7 A direct correlation was noted between severity of asthma during pregnancy and severity of maternal hypertension.

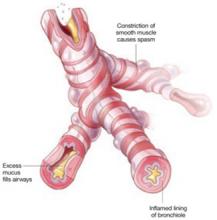

3 elements of an asthma attack

Asthma is characterized by airway obstruction and epithelial remodeling, caused by airway muscular spasm, excess mucus production, and inflammation. Bronchospasm is the hallmark of acute exacerbations, which manifest clinically as wheezing, shortness of breath, and nonproductive cough.

Greater risk of hemorrhage, drugs or no drugs

The risk of antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage increases in women with uncontrolled asthma, independent of drug usage.8 In fact, the increase in postpartum hemorrhage was most pronounced in women who did not take medication. The increased risk of hemorrhage may be related to hemostatic alterations in atopic patients, including deficient platelet aggregation, decreased platelet life span, and altered arachidonic acid metabolism.

Asthma drugs are well tolerated, but save oral steroids for acute disease

In a cohort of 817 women with asthma and 13,709 without, the only significant difference in neonatal outcome was an increased risk of hyperbilirubinemia in the infants of women taking oral steroids.10

A large multicenter study9 of perinatal outcomes in 2,123 women with asthma showed no adverse outcomes related to the use of inhaled beta-agonists, inhaled steroids, or theophylline. However, oral corticosteroid use was significantly associated with an increase in preterm births (<37 weeks) (P=.010) caused by premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, or for indicated reasons such as fetal distress, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), or preeclampsia.9 Oral corticosteroid use also was associated with low birth weight (<2,500 g) (P=.008). In addition, there was an increased cesarean delivery rate in the moderate-to-severe asthmatic group.11

No increase in congenital malformations was seen in gravidas with asthma taking a variety of medications, according to a 20-year study in Sweden.10,12 Recently, using data from the Swedish national birth registry, researchers conducted a subgroup analysis of 2,534 gravidas with first-trimester exposure to the inhaled corticosteroid budesonide, and found no increase in the rate of congenital anomalies.10,12 Based on this finding, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) changed budesonide from pregnancy category C to category B. Although other inhaled corticosteroids may be as safe, they are still classified as category C owing to a lack of clinical data. The FDA classification of several other frequently used asthma drugs is shown in TABLE 2.

Because of the increased risk of prematurity associated with oral steroids, asthma should be carefully controlled to avoid their use if at all possible. However, for severe exacerbations triggered by viral infection or other factors, oral steroids are indicated to reduce the likelihood of other, more significant risks, including death.