Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, et al. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2161–2170.

This interim analysis of a phase-3 double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the bivalent HPV vaccine (Cervarix), which targets HPV types 16 and 18, also was published last year. It enrolled more than 18,000 women 15 to 25 years old who had a mean length of follow-up of 15 months. The vaccine was 90.4% effective against CIN 2,3 associated with the targeted strains (types 16 and 18), the primary endpoint of the trial (TABLE). There was no significant difference in safety outcome between vaccine and placebo recipients.

This trial is ongoing, with final results expected in approximately 2 years. Based on interim findings, the vaccine has been approved for use in a number of countries, including all 27 European Union nations, and the manufacturer of the vaccine has filed an application for approval with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Screening is more effective when HPV testing is included—or used alone

Bulkmans NW, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764–1772.

Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589–1597.

Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579–1588.

These major studies compared cytology alone with HPV DNA testing for high-risk strains (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) and found HPV testing—with or without cytology—to be superior to cytology alone.

In a trial from the Netherlands, Bulkmans and colleagues randomly assigned more than 17,000 women 29 years and older to cytologic screening only or a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing. After 5 years of follow-up, all women were rescreened using both tests. The baseline screen including a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing identified 70% more CIN 3 lesions and cancers than did cytology alone. More important, during the subsequent round of screening, CIN 3 lesions and cancers decreased by 55% in the group initially screened with both tests.

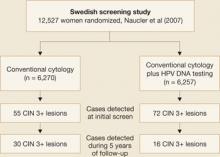

Naucler and associates had similar results in a prospective Swedish trial that randomized women to screening by cytology alone or a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing. During the initial round of screening, 31% more CIN 3 lesions and cancers were detected in the group screened with both tests (FIGURE 2). In subsequent rounds of screening, 47% fewer CIN 3 lesions or cancers were identified in this group.

Figure 2 Screening protocol that includes HPV DNA testing is superior, large trial confirmsTaken together, these two prospective studies clearly demonstrate that the addition of HPV DNA testing to cytology increases detection of high-grade lesions and reduces the incidence of high-grade neoplasia and cancers detected subsequently.

HPV testing is more sensitive, only slightly less specific, than cytology

In a cross-sectional study from Canada, Mayrand and colleagues compared HPV DNA testing and cytology during a single round of screening in more than 10,000 women. The findings were consistent with those of previous studies showing HPV DNA testing to be significantly more sensitive but somewhat less specific than cytology.3

The sensitivity of HPV testing for CIN 2,3 was 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 84–100), compared with 55% (95% CI, 34–77) for cytology. Specificity of HPV DNA testing and cytology was 94% and 97%, respectively. When the two tests were used together, sensitivity was 100% and specificity was 93%.

New consensus guidelines clarify screening in special populations

Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346–355.

Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:340–345.

The 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests clarify management of special populations such as adolescents, postmenopausal women, and patients with cervical adenocarcinoma in situ. Although the 2001 guidelines were widely adopted in the United States as the standard for managing women with abnormal screening tests—more than 500,000 copies were downloaded from Web site of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)4—it became apparent after their implementation in a variety of clinical settings that some clarification of the guidelines was needed.