The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Thrombosis is hypothesized to be the more common mechanism underlying cerebral palsy in many cases of maternal or fetal thrombophilia; for that reason, understanding the impact of maternal and fetal thrombophilia on pregnancy outcome is of paramount importance when counseling patients.

Is a maternal and fetal thrombophilia work-up needed in women who give birth to a term infant with cerebral palsy? Prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether that is the case. In this article, we review the literature on fetal thrombophilia and its role in explaining some cases of perinatal stroke that lead, ultimately, to cerebral palsy.

The several causes of cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy is the most common chronic motor disability of childhood. Approximately 2 to 2.5 of every 1,000 children are given a diagnosis of this disorder every year.1,2 The condition appears early in life; it is not the result of recognized progressive disease.1 Risk factors for cerebral palsy are multiple and heterogenous1,3,4-6:

- Prematurity. The risk of developing cerebral palsy correlates inversely with gestational age.7,8 A premature infant who weighs less than 1,500 g at birth has a risk of cerebral palsy that is 20 to 30 times greater than that of a full-term, normal-weight newborn.3,4

- Hypoxia and ischemia. These are the conditions most often implicated as the cause of cerebral palsy. Fetal heart-rate monitoring was introduced in the 1960s in the hope that interventions to prevent hypoxia and ischemia would reduce the incidence of cerebral palsy. But monitoring has not had that effect—most likely, because some cases of cerebral palsy are caused by perinatal stroke.9 In fact, a large, population-based study has demonstrated that potentially asphyxiating obstetrical conditions account for only about 6% of cases of cerebral palsy.6

- Thrombophilia. Several recent studies report an association between fetal thrombophilia and both neonatal stroke and cerebral palsy.10-14 That association provides a possible explanation for adverse pregnancy outcomes that have otherwise been ascribed to events during delivery.15-23 Although thrombophilia is a recognized risk factor for cerebral palsy, the strength of the association has still not been fully investigated. TABLE 1 and TABLE 2 summarize studies that have examined this association. Given the rarity of both inherited thrombophilias and cerebral palsy, however, an enormous number of cases would be required to fully establish a causal relationship.

TABLE 1

Case reports reveal an association

between fetal thrombophilias and cerebral palsy

| Thrombophilias present | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study (type) | Cases of CP | Number | Type |

| Harum et al36 (case report) | 1 | 1 | Factor V Leiden |

| Thorarensen et al37 (case report) | 3 | 3 | Factor V Leiden |

| Lynch et al2 (case series) | 8 | 8 | Factor V Leiden |

| Halliday et al38 (case series) | 55 | 5 | Factor V Leiden; prothrombin mutation |

| Smith et al39 (case series) | 38 | 7 | Factor VIIIc |

| Nelson et al40 (case series) | 31 | 20 | Factor V Leiden; protein C deficiency |

TABLE 2

How often is a fetal thrombophilia

the likely underlying cause of cerebral palsy?

| Thrombophilia* | Prevalence of CP† | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Factor V Leiden | 6.3% | 0.62 (0.37–1.05) |

| Prothrombin gene | 5.2% | 1.11 (0.59–2.06) |

| MTHFR 677 | 54.1% | 1.27 (0.97–1.66) |

| MTHFR 1298 | 39.4% | 1.08 (0.69–1.19) |

| MTHFR 677/1298 | 15.1% | 1.18 (0.82–1.69) |

| * Heterozygous or homozygous | ||

| † Among 354 subjects with thrombophilia studied41 | ||

| Key: MTHFR, methyltetrahydrofolate reductase | ||

“Thrombophilia” describes a spectrum of congenital or acquired coagulation disorders associated with venous and arterial thrombosis.24 These disorders can occur in the mother or in the fetus, or in both concomitantly.

Fetal thrombophilia has a reported incidence of 2.4 to 5.1 cases for every 100,000 births.25 Whereas maternal thrombophilia has a substantially higher incidence, both maternal and fetal thrombophilia can lead to adverse maternal and fetal events.

The incidence of specific inherited fetal thrombophilias is summarized in TABLE 3. Maternal thrombophilia is generally associated with various adverse pregnancy outcomes, particularly cerebral palsy and perinatal stroke.9,26

TABLE 3

Inherited thrombophilias among the general population

| Study | Number | Factor V Leiden | Protein gene mutation | MTHFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibson et al41 (2003) | 708 | 9.8% | 4.7% | 15.1%* |

| Dizon-Townson et al42 (2005) | 4,033 | 3.0% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Infante-Rivard et al43 (2002) | 472 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 43% to 49% |

| Stanley-Christian et al44 (2005) | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Currie et al45 (2002) | 46 | 13.0% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Livingston et al46 (2001) | 92 | 0 | 2% | 4% |

| Schlembach et al47 (2003) | 28 | 4.0% | 2% | Not reported |

| Dizon-Townson et al48 (1997) | 130 | 8.6% | Not reported | Not reported |

| * Heterozygous and homozygous carriers of MTHFR C677T and A1298C | ||||

| Key: MTHFR, methyltetrahydrofolate reductase | ||||

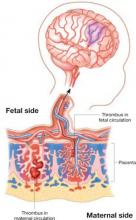

Thrombophilia leads to thrombosis at the maternal or fetal interface (FIGURE):

- When thrombosis occurs on the maternal side, the consequence may be severe preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, abruptio placenta, or fetal loss.27-29

- Thrombosis on the fetal side can be a source of emboli that bypass hepatic and pulmonary circulation and travel to the fetal brain.30 As a result, the newborn can sustain a catastrophic event such as perinatal arterial stroke via arterial thrombosis, cerebral sinus venous thrombosis, or renal vein thrombosis.25