The author reports no financial disclosure relevant to this article.

- Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) abscesses are best managed surgically; postprocedure antibiotics do not substantially improve outcome. The cure rate with incision and drainage alone is at least 90%.

- If incision and drainage fail to promote healing within 7 days, oral antibiotics of choice are trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and tetracycline

- Eradication of nasal carriage of CA-MRSA generally does not help prevent spread of clinical MRSA infection in communities.

CASE: Tender suprapubic lesion

A previously healthy, 22-year-old law school student arrives at your office complaining of “abdominal pain.” She is previously healthy; temperature is normal.

You discover on examination that she has an erythematous, indurated, and tender 3-cm lesion on the suprapubic region. The lesion has no point, but its center is boggy.

Should you prescribe an antibiotic? And should you cover immediately for CA-MRSA? What other factors might influence your decision about treatment?

The incidence of MRSA is increasing in communities across the United States, challenging assumptions about the evaluation and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. In this article, I outline a rational approach to managing patients who have a lesion likely to be caused by CA-MRSA ( TABLE 1 ).

TABLE

Suspect CA-MRSA infection? Consider this treatment scheme

| When a patient meets these criteria… | Provide this management… | And select from these antibiotics |

|---|---|---|

| Lesion nonfluctuant; patient afebrile, healthy (Class 1 infection) | If no drainable abscess, give a common first-line antibiotic for skin and soft-tissue infection; reassess for response | —Semisynthetic penicillin —Oral first- or second-generation cephalosporin —Macrolide —Clindamycin |

| Lesion, fluctuant or pustular, <5 cm in diameter; fever or no fever (Class 2) | Drain abscess surgically if possible; use incision and drainage presumptively for MRSA and monitor closely for response; inpatient management may be indicated | —Trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole —Tetracycline —Clindamycin |

| Lesion, >5 cm in diameter, toxic appearance or at least one unstable comorbidity or a limb-threatening infection (Class 3) | Admit; consider infectious disease consult | Broad-spectrum agent, including vancomycin, for MRSA coverage |

| Sepsis syndrome or life-threatening infection (necrotizing fasciitis)(Class 4) | Admit; institute aggressive surgical debridement; request infectious disease consult | Broad-spectrum agent, including vancomycin, for MRSA coverage |

| Source: Eron et al6 and CDC7 . | ||

When to suspect MRSA skin infection

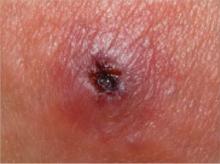

Patients who have a CA-MRSA skin infection often report a “spider bite” because the lesion appears suddenly and unexpectedly in an area where there is no history of trauma.1 Lesions often are pustular with central necrosis; there may be purulent drainage, redness, tenderness, and palpable fluctuance ( FIGURE ).

CA-MRSA skin lesions can occur anywhere on the body, though they appear most often in the axillae or the groin and buttocks. Patients may or may not have a fever.

Persons at increased risk of CA-MRSA disease include users of health clubs, participants in contact sports, men who have sex with men, children younger than 2 years, users of intravenous drugs, military personnel, and prisoners.2,3 Absence of these risk factors in a patient with a skin or soft-tissue infection does not, however, rule out MRSA.4

Regardless of the lesion’s appearance or the patient’s epidemiologic history, consider CA-MRSA if its prevalence in your community has reached 10% to 15%.

CA-MRSA can cause impetigo, but the often-benign nature of this clinical infection makes management decisions less crucial. However, do hospitalize any patient who has a MRSA infection who also exhibits fever or hypothermia, tachycardia >100 bpm, or hypotension with a systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or 20 mm Hg below baseline. A skin lesion >5 cm in diameter also likely requires hospitalization and a parenteral antibiotic.5

FIGURE Class-2 CA-MRSA lesion

This raised, red lesion contains a central eschar with dried pus. Such lesions are generally very tender and often fluctuant when palpated.

Incision and drainage are most important

Several management schemes have been proposed to guide the appropriate level of therapy based on presenting characteristics.6,7 If a lesion is clearly fluctuant, incise it and drain the fluid, or refer the patient for surgical consultation. If the lesion is not clearly fluctuant, needle aspiration may help to determine the need for more extensive incision and drainage or to collect a specimen for culture. Although culture of a skin lesion may not have been routine in the past, the advent of CA-MRSA has made it so—particularly given that MRSA lesions may not be clinically distinguishable from those caused by nonresistant S aureus.