Another important and often overlooked limitation on this type of discussion is the time constraints that busy clinicians face, especially with the low reimbursement offered by managed care. Sexual problems can hardly be adequately discussed in 7 to 10 minutes.

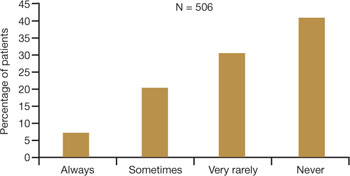

FIGURE 2 Do physicians ask about dyspareunia? Most women surveyed said “rarely” or “never”

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

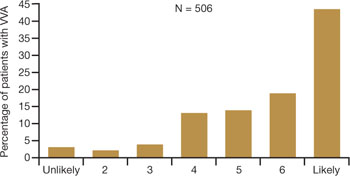

FIGURE 3 Are these women likely to seek treatment?

Simon JA, Komi J. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) negatively impacts sexual function, psychosocial well-being, and partner relationships. Poster presented at North American Menopause Association Annual Meeting; October 3-6, 2007; Dallas, Texas.

Women have performance anxiety, too

It is well known that men with even a mild degree of erectile dysfunction can suffer from performance anxiety, but the fact that women can also suffer from this phenomenon is not given as much attention. Such anxiety can be a factor in relationship difficulties. With both partners perhaps feeling anxious about sexual performance, a couple may avoid even simple acts of affection, such as holding hands, to avoid raising the other’s expectations.

Exacerbating the situation is the fact that many men use widely prescribed phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, whereas women are contending with barriers to continued sexual activity as they age. It does not take a psychologist to understand that this imbalance often adds to emotional strain and tension between partners.

Popular media address the issue

Look beyond what our postmenopausal patients tell us directly—to the popular media and online forums—to appreciate the scope of sexual pain as a major issue among postmenopausal women. Evidence of psychosocial effects is found on numerous Web sites—some from organizations, others designed by women seeking help from each other.

Red Hot Mamas

This organization aims to empower women through menopause education. Highlighted in the Winter 2007/2008 Red Hot Mamas Report is a survey done in conjunction with Harris Interactive exploring the impact of menopausal symptoms on a woman’s sex life, which found that 47% of women who have VVA have avoided or stopped sex completely because it was uncomfortable, compared with 23% of normal women.

Power Surge

This Web site offers a list of strategies for dealing with sexual pain, including an overview of hormone-based prescription and nonprescription products, along with a variety of over-the-counter, natural, holistic, and herbal therapies for treating dyspareunia.

What is the physician’s role?

Given the epidemic of sexual pain, it is crucial that physicians and others who care for postmenopausal women increase their awareness of this issue and pay special attention to its psychosocial parameters.

Ask patients about sexual function in general and dyspareunia in particular as part of the routine annual visit. A simple opening “Yes/No” question, such as “Are you sexually active?” can lead to further questions appropriate to the patient. For example, if the answer is “No,” the follow-up question might be, “Does that bother you or your partner?” Further discussion may uncover whether the lack of sexual activity is a cause of distress and identify which variables are involved.

If, instead, the answer is “Yes,” follow-up questions can identify the presence of common postmenopausal physical issues, such as vaginal dryness and difficulty with lubrication. The visit then can turn to strategies to ameliorate those conditions.

When a patient reports dyspareunia, further diagnostic information such as precise location, degree of arousal, and reaction to pain can help determine the appropriate course of treatment. For an approach to this aspect of ascertaining patient history, see the list of sample questions above.12

During the physical, pay particular attention to any physical abnormalities or organic causes of sexual pain. Questions designed to characterize the location and nature of the pain can pinpoint the cause. Sexual pain arising from VVA is likely to 1) be localized at the introitus and 2) occur with penile entry.

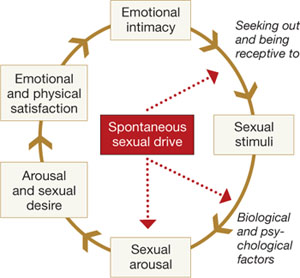

Since the mid-1990s, the availability of validated scales to measure female sexual function has increased rapidly and enabled researchers to better identify, quantify, and evaluate treatments for female sexual dysfunction.7 Over time, we have moved away from the somewhat mechanical sequence inherent in the linear progression of desire leading to genital stimulation followed by arousal and orgasm toward an appreciation of the multiple physical, emotional, and subjective factors that are at play in women’s sexual function.

By 1998, a classification scheme was developed to further the means to study and discuss disorders of desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual pain.8 Further contextual definitions of sexual dysfunction are under consideration.13

Basson proposed one new model of female sexual function (see the diagram), and observed that

"…women identify many reasons they are sexual over and beyond inherent sexual drive or “hunger.” Women tell of wanting to increase emotional closeness, commitment, sharing, tenderness, and tolerance, and to show the partner that he or she has been missed (emotionally or physically). Such intimacy-based reasons motivate the woman to find a way to become sexually aroused. This arousal is not spontaneous but triggered by deliberately sought sexual stimuli."13

Intimacy-based model of female sexual response cycle

In this flow of physical and emotional variables involved in female sexual function, categories interact. For example, low desire can be and is frequently secondary to the anticipation of pain during sexual intercourse. Arousal can be hampered by lack of vaginal lubrication—perhaps inhibited by the anticipation of pain. Secondary orgasmic disorders can result from low desire, difficulty of arousal, and sexual pain.14 Sexual pain can affect sexual function at any point on this continuum.