Take a history and examine the patient. Before scanning your own patient, take a short history and perform a bimanual, palpatory pelvic exam. You may need to examine her again after the scan to verify a sonographic finding.

It is doubly important to take a history if you are scanning a referred patient. Omitting this element is no excuse for overlooking a disease or pathology.

A bimanual, palpatory pelvic exam may also be recommended for some referred patients.

A transvaginal scan is not always possible. There are a number of reasons why the transvaginal approach may not be advisable for some patients, including virginal status, atrophic postmenopausal vagina, agenesis of the vagina, and transverse vaginal septae. In such cases, the best alternative is a transrectal scan, which makes it possible to image the pelvic organs from almost exactly the same vantage point as transvaginal US.2 With proper explanation (particularly with virginal patients), the initial reluctance and apprehension can usually be assuaged.

Don’t trust the referral slip. We recommend that you read, but do not overly trust, the referral slip. It often offers little useful information.

Helpful scanning techniques

Consider applying these maneuvers:

- place your non-scanning hand on the patient’s abdomen to help mobilize the pelvic contents as the transvaginal probe slides across the organs

- use the probe as an “eye” while your palpating finger touches the cervix, uterus, ovaries, and any adnexal mass. Observe the mobility of these structures in relation to each other and the pelvic wall. This technique yields what is often referred to as the “sliding organs” sign. It is possible to identify pelvic adhesions (if the structures do not slide freely) or rule them out (if they do)

- pinpoint the origin of any pain the patient may have by touching the ovary, cervix, and any adnexal mass. This technique is important in cases of ectopic pregnancy, adnexal torsion, or inflammatory disease of the pelvis or adnexae.

Start with a basic scan of key structures

On the way “in” toward the adnexae, take the time to look at the bladder and urethra (FIGURE 1). Some common pathologies of the bladder are diverticulae; calculi; and a thick and vascular bladder wall suggestive of cancer or endometrioma. Ask the patient whether she has experienced any hematuria if any of these pathologies are detected.

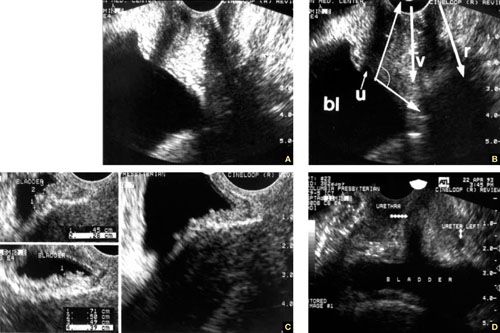

FIGURE 1 Imaging the bladder

(A, B) The bladder (bl), urethra (u), vagina (v), and rectum (r) appear in their proper relation in this sagittal view. The posterior angle of the bladder is also apparent (arrow closing an angle of about 110°). (C) Excessive thickness of the bladder wall suggests that this patient has cystitis. (D) Coronal view of the bladder and urethra (solid arrows).

Also take a look at the cervix, searching for Nabothian cysts, endocervical polyps, extreme vascularization (a possible indicator of cervical cancer), and prolapsing submucous myomas (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2 Uncommon pathology

A submucous myoma prolapses into the cervical canal in a 13-week intrauterine pregnancy. (A) Grayscale sagittal image and (B) outline view of the same image. (C,D) Color and power Doppler images show the blood supply to the myoma from the uterine cavity.

While you are looking, attempt to scan both kidneys and Morrison’s pouch. Large adnexal masses or fibroids of the uterus may put pressure on the ureter, causing various degrees of hydronephrosis.

Sometimes, when the right kidney is correctly imaged below the liver, you may detect fluid in the space between them (called Morrison’s space). This information has clear value that may aid in diagnosing the main pathology (i.e., ruptured tubal pregnancy, ascites, etc.).

Imaging of the ovaries

The best way to scan the ovaries is to use a high-frequency (4–9 MHz) transvaginal probe. In general, as the frequency of the probe increases, so does resolution of the image—but the ability to penetrate tissue diminishes. For this reason, for abdominal imaging, a 3-MHz probe is often used. For a transvaginal scan, in which the probe can be placed near an ovary, a 5-MHz probe is common. And for a scan of, say, the parathyroid gland, a 12-MHz probe is utilized.

During the reproductive years, the ovaries can be localized by their sonographic markers—the follicles (FIGURE 3A). The ovaries usually lie near the large hypogastric blood vessels (FIGURE 3B). During the secretory phase of the cycle, look for the corpus luteum, switching on the color or power Doppler mode to help locate it (FIGURES 3C, 3D).

The ovaries usually can be distinguished by their relative anechoic sono-texture in juxtaposition to the surrounding, constantly peristalsing small bowel. This strategy is the only help for spotting the ovaries in menopause, when they lose their follicles.