Part 1: A Starting Point (September 2010)

Part 3: Ovarian neoplasms (November 2010)

Part 4: The fallopian tubes (December 2010)

Scanning the ovaries is no simple task. As we mentioned in Part 1 of this four-part series, the practitioner must use the right equipment, take basic preparatory steps, be watchful for clues in the history, and reach a conclusion about what he or she sees. Not only that: The ultrasonographer must be extraordinarily vigilant, paying close attention to multiple characteristics of any mass, from thickness of the wall to the presence of papillations or a blood supply—signs of potential malignancy.

In this article, we detail the traits of various types of non-neoplastic ovarian masses, including:

- functional cysts—follicles, the corpus luteum, and theca lutein cysts

- nonfunctional cysts—serous masses and endometriomas

- cystadenofibromas. Although these masses are usually categorized histo-logically as neoplasms, we include them here due to their almost daily appearance in a busy gynecologic ultrasonographic (US) facility.

In Part 3, we will cover ovarian neoplasms, and in Part 4, our focus will be tubal entities such as ectopic pregnancy and torsion.

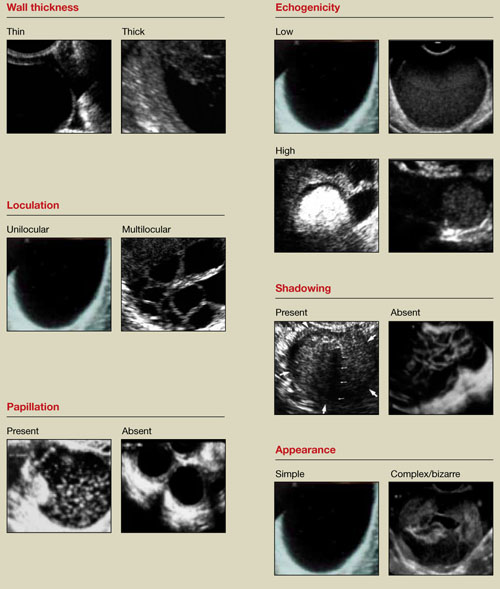

FIGURE 1 What is a mass made of? 6 morphologic building blocks

Take an inventory of the mass

Any adnexal mass should be assessed in light of its essential characteristics (Figure 1).

Wall structure. Pay attention to thickness. We use an arbitrary cutoff of 4 mm, giving extra scrutiny to thicknesses exceeding that measurement. In our experience, the thicker the wall, the more likely the mass is to be malignant.

Septation and loculation. A mass is typically unilocular or multilocular. Multilocularity is more common in tumors of low malignant potential and malignant neoplasms.

Papillation. Any internal or external papillae or excrescences should draw your attention. Papillarity in an ovarian mass renders that mass suspicious for malignancy.

Measure (height and width) any papillae that are identified, and document them. Because papillae are associated with ovarian malignancy, further assessment is warranted immediately. The first step is determining whether the papillations contain blood vessels—a task for which color and power Doppler are helpful. We prefer power Doppler because it is more sensitive, detecting blood-flow velocity in the lowest detectable range of 2 cm/s, and because it is not directionally influenced.

Papillae that contain blood vessels with detectable flow are suspicious for malignancy.

Exacoustos and colleagues found that papillae as large as 15 mm in height and 10 mm in width (base) were present in 48% of borderline ovarian tumors but in only 4% of benign and 4% of malignant tumors. However, when the intracystic solid tissue exceeded those dimensions, the lesions were present in 48% of invasive ovarian tumors, 18% of borderline ovarian tumors, and 7% of benign masses.1

Internal echo-structure. A mass can be anechoic, a finding that usually indicates the presence of clear fluid. Mostly solid masses are echogenic. And masses that contain particulate matter, such as blood, cellular matter, or even mucous material, usually have echogenicity of a low level, often described as a “ground-glass” appearance. A mass can also have mixed echo-genicity, a finding usually found in cases involving teratoma or malignancy.

Shadowing. If it is present, it may signify the presence of an extremely dense, solid tissue, such as bone or calcification. The diagnosis of a benign teratoma (i.e., dermoid cyst) should be entertained if shadowing is present in a hyperechoic nodule or mass. Malignant masses very rarely, if ever, display frank shadowing.

Overall appearance. On rare occasions, a bizarre shape or “complex” appearance (as it is termed in most radiology reports) may indicate a malignant mass. More likely it indicates the presence of a teratoma, cystadenoma, or even an atypical corpus luteum. In some reports generated by US laboratories, the term “complex” is applied to all structures other than simple cysts.

Size. The size of a mass can be misleading, as small ovarian lesions with the appropriate sonographic characteristics may be malignant and some larger ones without those characteristics may not be. However, it is understood that the larger an ovarian lesion, the more likely it is a tumor. One important distinction: The amount of fluid in a cystic structure or the amount of old blood in an endometrioma is not the disease process…it is the byproduct of the process. So an 8-cm endometrioma may create fewer pain or fertility issues than a 2- or 3-cm endometrioma. Similarly, the amount of “chocolate” fluid is not automatically indicative of the amount of active endometriotic glands or their sequelae!2

Ascites. If it is present, it should be recorded and investigated further because it may be caused by a malignant intra-abdominal tumor.