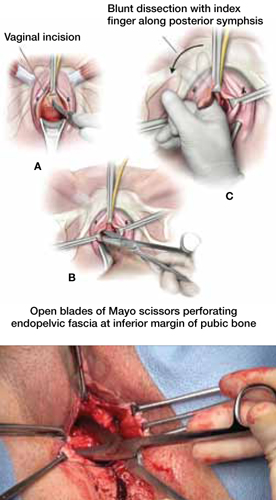

Create vaginal flaps that have sufficient mobility to ensure tension-free closure over the sling. Carry out dissection laterally and anteriorly until you encounter the endopelvic fascia, then incise the endopelvic fascia and dissect it from the posterior surface of the pubis to enter the retropubic space.

Although blunt dissection sometimes can be performed, sharp dissection with Mayo scissors is often required, especially in cases that involve recurrent stress incontinence (FIGURE 4).

FIGURE 4 Dissect the vagina

A. Use an inverted “U” or vertical incision on the vaginal mucosa overlying the midurethra and bladder. B. Carefully dissect the tissue to the pubic rami bilaterally until the urogenital diaphragm is identified, then sharply penetrate it using Mayo scissors. C. Enlarge the opening by repeating the procedure on the opposite side.

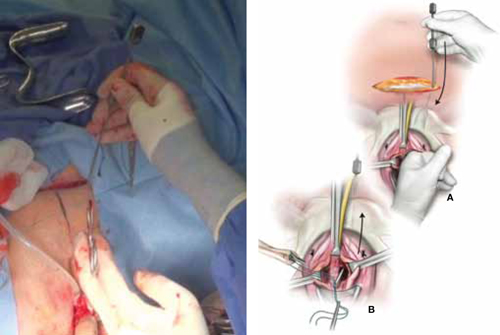

8. Pass retropubic needles

Pass Stamey needles or long clamps through the retropubic space from the open abdominal wound immediately posterior to the pubic bone, approximately 4 cm apart. You can maintain distal control of the needles by direct finger guidance through the vaginal incision. Be careful to advance the tip of the needle adjacent to the posterior surface of the pubic bone to avoid inadvertent bladder injury (FIGURE 5). Proper bladder drainage also helps to minimize injury to the bladder, which may be closely adherent to the pubis, especially if a prior retropubic procedure has been performed, as in Case 1.

FIGURE 5 Place the sling

A. Insert the Stamey needle through the rectus fascia and guide it into the vagina with the index finger placed against the tip of the needle. B. Thread both ends of the polyester suture into the eye of the Stamey needle and then retract the needle carefully until the suture ends are delivered abdominally at the level of the fascia.

9. Rule out bladder injury

Careful cystoscopic examination of the bladder is mandatory after passing the needles to rule out inadvertent injury. Injuries to the bladder typically occur at the 1 o’clock and 11 o’clock positions, so use a 70° lens, and fill the bladder completely to expand any mucosal redundancy. Wiggle the needles or clamps to help localize their position relative to the bladder wall.

10. Deploy the sling

Thread the free ends of the sutures affixed to the sling into the ends of the Stamey needles—or grasp them with clamps—and pull each suture up to the anterior abdominal wall through the retropubic space (FIGURE 5). Keep the sling centered and flat at the area of the bladder neck.

Some surgeons fix the sling in the midline to the underlying periurethral tissue using numerous delayed absorbable sutures. We prefer to leave the sling unattached to the underlying urethra and bladder neck.

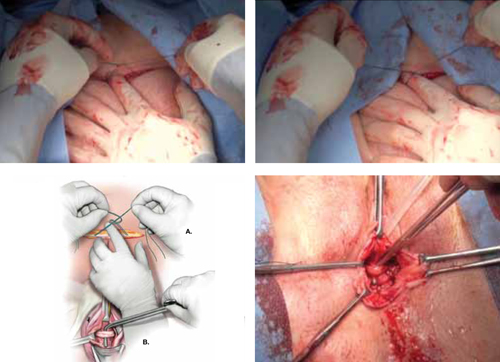

11. Tension the sling

Various techniques are applicable. To ensure adequate “looseness,” we tie the sutures across the midline while holding a right-angle clamp between the sling material and the posterior urethral surface. The goal is for the sling to prevent the descent of the proximal urethra during increases in abdominal pressure without creating any outlet obstruction to the normal flow of urine (FIGURE 6).

FIGURE 6 Tension the sling

A. Tie the suspensory sutures abdominally above the fascial closure line. Tie the sutures across the assistant’s index finger to avoid excessive tension. B. Assess the tension using a right-angle clamp placed between the pubovaginal sling and the vagina.

12. Close the incisions

Close the abdominal skin incision using 3-0 and 4-0 absorbable sutures. Use 3-0 absorbable sutures to close the vaginal mucosa. We prefer to close the vagina after completion of the tensioning procedure, but some surgeons complete this step prior to tensioning.

13. Place a catheter, packing material

Place a bladder catheter and vaginal gauze packing. Both the catheter and gauze may be removed after 24 hours. If the patient is unable to void at that time, teach her intermittent self-catheterization, or place an indwelling Foley catheter for 1 week.

Outcomes show good efficacy

Pubovaginal slings are highly effective, with success rates between 50% and 75% after follow-up as long as 10 years.1 In 2011, Blaivas and Chaikin reported 4-year follow-up data, with improvement or cure in 100% of patients with uncomplicated SUI and in as many as 93% of patients in more complicated cases.2 Most failures were due to urge incontinence and occurred within the first 6 postoperative months; 3% of these urge patients were thought to have developed de novo urge incontinence.

Other studies have found de novo urgency and storage symptoms in as many as 23% of patients, with 11% of patients reporting voiding dysfunction and as many as 7.8% requiring long-term self-catheterization.1