Any diagnosis of GDM warrants aggressive treatment

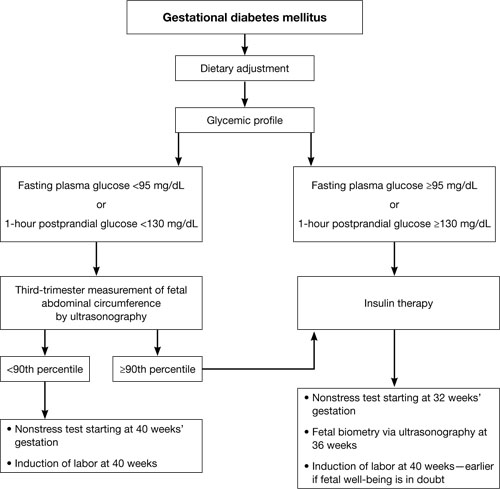

Perhaps the single greatest controversy in the field of diabetes centers on the level of hyperglycemia at which aggressive treatment of GDM should begin. Traditionally, aggressive therapy (i.e., insulin) was not initiated until the fasting plasma glucose level reached 95 mg/dL or higher or the 1-hour glucose level reached 130 mg/dL or higher (ALGORITHM). However, recent studies suggest that aggressive treatment should be administered for any diagnosis of GDM.

Typical management plan for gestational diabetesFor example, the HAPO study was designed to determine the level of glucose intolerance during pregnancy, short of diabetes, associated with adverse outcomes.16 It found that even mild hyperglycemia is associated with adverse fetal outcomes and that diagnostic criteria for GDM cannot easily be based on any particular level of hyperglycemia.

Several other studies have demonstrated that aggressive treatment of mild GDM can ameliorate many of its negative effects. In 2005, for instance, Bonomo and coworkers explored the effect on newborns of treating a very mild level of gestational glucose intolerance among 300 women.18 The randomized trial involved three groups:

- Group A – standard management, which entailed no special care, diet, or pharmacotherapy

- Group B – dietary treatment and regular monitoring

- Group C – randomly selected pregnant women who were matched by BMI and age and who had normal screening test results.

The women in Group B experienced significant improvements in fasting and 2-hour postprandial glucose levels. In addition, the fasting glucose level at delivery was significantly lower in Group B, compared with the other two groups. More important, fewer LGA infants were born to the women in Group B (6.0%) than in Group A (14.0%) and Group C (9.1%).

Landon and colleagues obtained similar findings when they randomized almost 1,000 pregnant women who had mild GDM to 1) usual prenatal care or 2) dietary intervention, self-monitoring of blood glucose, and, if necessary, insulin therapy.19

Insulin analogs have joined the treatment options

Standard treatment for GDM involves diet and nutritional therapy and, when needed, insulin. A diet that limits carbohydrate in-take can significantly reduce glycemia after meals in women who have GDM.20

For years, human insulin was the only option for treating diabetes that cannot be controlled by diet and lifestyle modifications alone. Recently, however, several insulin analogs have come on the market. Only two of them have been well studied in pregnancy:

- 28B-L-lysine-29B-L-proline insulin (lispro)

- 28B-aspartic acid insulin (aspart).

These two analogs have been tested primarily in the setting of type 1 diabetes, but both improve postprandial glucose excursions, compared with human regular insulin, and both may be associated with a lower risk of delayed postprandial hypoglycemia.21,22

Some oral agents appear to be safe

Several oral antihyperglycemic agents are available for the management of diabetes (TABLE). However, in the past, oral agents were not used in pregnant women out of concern over reports of fetal anomalies and other adverse outcomes in animal studies and some human cases. More recent evidence suggests that glyburide and metformin are safe and effective for use in GDM.23-25

Oral antihyperglycemic agents and their potential side effects

| Class | Agents | Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin secretagogue | Sulfonylureas and meglitinides such as glyburide, glipizide, glimepiride, repaglinide, nateglinide | Hypoglycemia if caloric intake is reduced Some are long-acting (increasing risk of prolonged hypoglycemia) |

| Biguanide | Metformin | Risk of lactic acidosis when used in the setting of renal dysfunction, circulatory compromise, or hypoxemia Relatively slow onset of action GI complications: nausea, diarrhea |

| Thiazoladinedione | Rosiglitazone, pioglitazone | Long delay to onset of action (2–3 weeks) Associated with fluid retention (particularly when used with insulin) and increased risk of congestive heart failure Use contraindicated in presence of liver disease or elevated transaminases |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor | Acarbose, miglitol | Prandial/meal agent (no effect in the fasting patient) Abdominal bloating and flatus Pure dextrose is required to treat hypoglycemia that occurs in the setting of these agents |

| Glucagon-like peptide–1 mimetic | Exenatide | Newer agents with limited inpatient experience Abdominal bloating and nausea secondary to delayed gastric emptying |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor | Sitagliptin | Newer agent with limited inpatient experience |

Langer and coworkers compared glyburide with insulin in the management of GDM and found the agents to be equally effective, with comparable levels of risk of large size for gestational age, macrosomia, hypoglycemia (in infants), NICU admission, and fetal anomaly.23 Subsequent studies have confirmed these findings, although at least one suggests that women who have a high fasting plasma glucose level may not respond adequately to glyburide.26 None of these studies has been large enough or long enough to truly assess whether these oral medications are equivalent to insulin in the management of GDM without posing significant long-term complications for mothers or babies, or both.