DENVER – The obesity epidemic has been a major driver of the steep rise in cesarean section rates documented nationally since the year 2000.

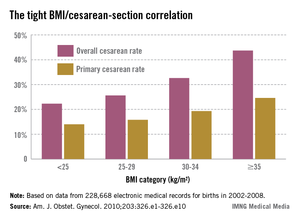

The contemporary trend is nicely captured by data on nearly 207,000 pregnancies in the mid-to-late years of the past decade collected by the Consortium on Safe Labor, a group of 19 university and community hospitals in all nine American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists districts. As prepregnancy body mass index increased, so did the cesarean section rate, Dr. Mark Alanis observed at the annual meeting of the Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists.

The Consortium used as their highest body mass index (BMI) category those women with a prepregnancy BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, who made up 21% of their study population. Nationally, 7.6% of the obstetric population is extremely obese as defined by a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more. The superobese – women with a prepregnancy BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more – make up a smaller subset, but they pose a special challenge for obstetricians. In the three studies that have examined cesarean section rates in superobese patients, one of which was conducted by Dr. Alanis, the rates were 55%, 49%, and 56%.

"It makes you wonder if it’s worth doing a randomized, controlled trial of scheduled primary cesarean section for women with a BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more. Is it more cost effective to try to do labor or just do the cesarean section? We don’t know," he said.

Why do obese women have a higher rate of cesarean section? The answer is beyond dispute, yet not widely appreciated; it’s because obese women tend to have ineffective uterine contractions in early labor, according to Dr. Alanis of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Persuasive evidence exists that greater body weight correlates with slowed cervical dilation. The first stage of labor is prolonged by about 2 hours in obese women. Dystocia occurs before 7 cm.

"You do these cesarean sections between 4 and 7 cm. You don’t do them after 7 cm very often," he noted. "The bottom line is if you can get your obese patient past 7 cm and she’s clearly in active labor, she’ll deliver just as easily as a lean patient."

Compelling data provided by the National Institutes of Health Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network show no differences in uterine forces or the length of the second stage of labor depending upon prepregnancy BMI in 5,341 nulliparous women.

"Maternal BMI in nulliparous women reaching the second stage is not associated with a higher incidence of cesarean delivery," according to the investigators (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:1309-13).

This finding confirms earlier work by Australian/New Zealand clinical trialists in a study involving 2,629 nulliparous women who went into labor after 37 weeks’ gestation. Being overweight or obese, respectively, was associated with adjusted 39% and 2.9-fold increased likelihood of cesarean delivery during the first stage of labor, compared with normal-weight women, but no increase in second-stage cesarean delivery (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:1315-22).

These findings of an overall longer duration and slower progression of the early part of the first stage of labor have led to a proposal for adoption of a separate obese labor curve (Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120:130-5).

"We probably should," according to Dr. Alanis.

The indication for cesarean section in obese patients is disproportionately failure to progress. Fetal distress as a trigger for cesarean delivery is not more common than in normal-weight women.

The explanation for the slower course of first-stage labor in obese women remains unclear, according to Dr. Alanis. Neither smooth muscle content nor contraction strength differs between obese and leaner women.

Dr. Alanis offers vaginal birth after cesarean section to obese patients he considers to have a decent chance of success. But he explains to them that they have a higher risk of uterine rupture, are more likely to develop endometritis, and are less likely to have a successful vaginal delivery than are normal-weight women, based upon data from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

"So approach TOLAC [trial of labor after cesarean] cautiously," he advised.

Dr. Alanis reported having no financial interests germane to his presentation.