Article

How can pregnant women safely relieve low-back pain?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER: ACETAMINOPHEN IS SAFE for use in pregnancy but lacks evidence of efficacy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, usual...

Jaimey M. Pauli, MD, is Assistant Professor, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Penn State University College of Medicine, and Attending Perinatologist at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

John T. Repke, MD, is University Professor and Chairman of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Penn State University College of Medicine. He is also Obstetrician-Gynecologist-in-Chief at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania. Dr. Repke serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Related Article: Noninvasive prenatal DNA testing: A survey of who is using it, and how (Audiocast, June 2013)

The problem of false positives

This issue was addressed by Mennuti and colleagues, who presented eight cases of abnormal cell-free fetal DNA results that were not confirmed by invasive testing.

There are few prospective data about the source of false-positive results; potential mechanisms include an inadequate fetal fraction of cell-free DNA, maternal or placental mosaicism, and a vanishing twin.

Mennuti and colleagues propose that a registry of false-positive and false-negative results be established to gather further data. They also note that as low-risk patients and aneuploidies of lower and lower prevalence are incorporated into noninvasive testing, the false-positive rate will rise. Their findings have implications for patient counseling, patient distress, invasive testing, and reimbursement.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Cell-free fetal DNA is a rapidly expanding screening technology, but it is not ready to replace diagnostic testing. Don’t throw away those CVS and amniocentesis kits just yet—we are a long way from a completely noninvasive world.

WHEN IT COMES TO GESTATIONAL DIABETES, LESS MAY BE MORE

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin #137: Gestational diabetes mellitus. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):406–416.

Gestational diabetes accounts for 90% of diabetic pregnancies, and its incidence has been increasing in the United States along with the obesity epidemic. In recent years, there has been some debate about the best way to screen for, diagnose, and treat gestational diabetes.

Multiple criteria exist for a positive 1-hour (130–140 mg/dL) or 3-hour glucose tolerance test (Carpenter and Coustan vs National Diabetes Data Group), without comparative trials or consensus as to which version is best. Lower cutoffs increase the rate of gestational diabetes by as much as 50%, whereas higher cutoffs lower the false-positive rate and reduce the need for additional tests.

Some groups have recommended moving away from the traditional two-step process to a one-step approach that utilizes the 2-hour, 75-g glucose tolerance test commonly used outside of pregnancy. They argue that this approach would simplify and standardize the process and could improve outcomes in “borderline” pregnancies that would have been missed by less stringent guidelines.

However, the baseline rate of gestational diabetes using this one-step approach would likely increase from 7% to 18% or higher, depending on the patient population. Such an increase would trigger a huge rise in costs and resources needed to care for these patients, without data on outcomes or appropriate therapy for this expanded group of women with gestational diabetes.

Treatment isn't clear-cut, either

Treatment of gestational diabetes centers on labor-intensive glucose monitoring, nutritional interventions, and insulin therapy.

Until recently, the use of oral hypoglycemic agents was not recommended due to limited data. Multiple studies now have been performed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of glyburide and metformin in pregnancy, demonstrating glucose control similar to that achieved with insulin without short-term adverse effects in the mother or newborn. However, as many as 20% to 40% of women using glyburide and 50% of those using metformin require the addition of insulin for adequate glucose control. The long-term effects of these medications are unknown.

Related Article: Does myo-inositol supplementation reduce the rate of gestational diabetes in pregnant women with a family history of type 2 diabetes? E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA (Examining the Evidence, June 2013)

ACOG weighs in

In an attempt to clarify optimal screening, diagnosis, and treatment, ACOG updated its practice bulletin on gestational diabetes in August 2013. Among its recommendations:

Avoid the 2-hour glucose tolerance test because there is no demonstrated benefit for the increased number of mothers (and their fetuses) that would be identified by this approach. Rather, use the two-step approach of a 1-hour 50-g glucose tolerance test followed by a 3-hour 100-g glucose tolerance test.

In regard to the 1-hour test, ACOG finds either 135 or 140 mg/dL acceptable as a cutoff but recommends that each practice choose one value as a standard and use it consistently. For the 3-hour test, ACOG recommends that each practice choose the version that best fits its population and prevalence of diabetes. At our institution, for example, we have chosen a 1-hour cutoff of 140 mg/dL and the National Diabetes Data Group criteria for the 3-hour test (105, 190, 165, and 145 mg/dL).

Oral glyburide or metformin may be used to treat gestational diabetes, but glyburide (starting at 2.5 mg/d) may be the better choice for glucose control.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER: ACETAMINOPHEN IS SAFE for use in pregnancy but lacks evidence of efficacy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, usual...

It is higher after elective primary cesarean.

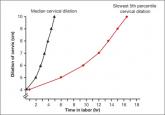

We are in a new era. Our patients, and their labors, have changed on a global scale. To optimally manage labor you need to use these new norms in...

Vaccination coverage is only around 50% for pregnant women

No. This post hoc analysis from the Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial at Term (HYPITAT) found that, contrary to widely held belief...