Expert Commentary

Does mediolateral episiotomy reduce the risk of anal sphincter injury in operative vaginal delivery?

Yes.

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, is Louis E. Phaneuf Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tufts University School of Medicine, and Chairman of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Norwitz serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Strengths of the study include the fact that it was conducted at a single center and had a large sample number. Weaknesses include its retrospective design and the fact that one major outcome (namely, failed operative vaginal delivery leading to cesarean) was not examined. This study was not designed or powered to examine neonatal outcomes.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

These data demonstrate that midwives can perform operative vaginal deliveries using either forceps or vacuum with a rate of maternal morbidity equivalent to those performed by physicians.

Are these findings truly revolutionary? Although midwives do not perform cesarean deliveries, they do perform and repair episiotomies when indicated. Restricting instrumental vaginal deliveries to physicians alone may be motivated more by tradition and logistics than concerns over patient safety. Indeed, the ability of a midwife working in a remote area to perform an instrumental vaginal delivery in an emergency situation may be highly beneficial to perinatal outcome, although it should be stressed that such an approach ought to be limited to practitioners who have undergone rigorous formal training.

Other benefits of midwives performing operative vaginal deliveries may include increased autonomy for the midwifery providers, improvements in physician-midwife interactions, and enhanced continuity of care for women.

IN THE PIPELINE: THE ODÓN DEVICE FOR OPERATIVE VAGINAL DELIVERY

World Health Organization Odón Device Research Group. Feasibility and safety study of a new device (Odón device) for assisted vaginal deliveries: Study protocol. Reprod Health. 2013;10:33.

Childbirth remains a risky venture. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 2.6 million babies are stillborn and 260,000 women die in childbirth each year, with developing countries disproportionately affected. Many of these adverse events result from complications at the time of delivery. Instrumental vaginal delivery is used to shorten the second stage of labor and improve perinatal and maternal outcomes.

Operative vaginal delivery likely does reduce the rate of stillbirth and early neonatal death and lower the cesarean delivery rate, but the instruments themselves do occasionally cause maternal and fetal injury, including cephalohematoma, retinal hemorrhage, facial nerve palsy, and skull fractures. Although numerous modifications to the design of forceps and the vacuum extractor have been made over the years, no new technology has been introduced for centuries.

In 2005, Mr. Jorge Odón, a car mechanic from Argentina with no formal training in medicine or obstetrics (aside from being the father of five), came up with an idea for a novel technique to assist in delivery. He was inspired by a simple trick he used to entertain his friends. It involved removing a loose cork from the inside of an empty bottle using a plastic bag. It occurred to him one day that this same scientific principle could be used to expedite delivery of the fetal head from the birth canal, and so he built the first prototype. The device has since been named in his honor.

Description of the Odón device

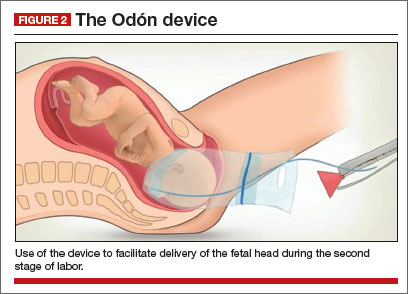

The Odón device consists of a tube containing a polyethylene bag. The tube is inserted into the birth canal and the bag is deployed and inflated to create a plastic sleeve that hugs the baby’s head. The applicator tube is then discarded and traction is applied to the plastic bag to move the head (and the entire fetus) down the birth canal (FIGURE 2).

![]()

The advantages of the Odón device are that it is:

Current stage of development

The Odón device already has been piloted in the United States and South America. The WHO plans to introduce it into the obstetric armamentarium in a three-phase clinical trial outlined in the Odón Device Research Project report. The first phase is under way and involves testing the device under normal delivery conditions in tertiary hospitals in Argentina and South Africa. The next two phases will 1) assess its efficacy in women with a prolonged second stage of labor but no “fetal distress” and 2) compare its performance head-to-head against the vacuum extractor and forceps.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Enthusiasm for the Odón device is fueled by its simplicity and the likelihood that midlevel providers working in remote obstetric units can be trained in its use, thereby increasing access to an important modality of emergency obstetric care. This is particularly important in centers that lack immediate access to cesarean delivery capabilities. Whether the device can be used in developing countries to more effectively manage the second stage of labor and thereby reduce infectious morbidity and pelvic floor injuries has yet to be confirmed but is a testable hypothesis.

Yes.

Planned home birth was associated with a significantly greater likelihood of a 5-minute Apgar score less than 4, compared with hospital birth (0....

Does your labor unit have such a list? Here, key components to get you started.

No. This retrospective cohort study found a significantly longer latent phase when labor was induced, compared with spontaneous labor. Harper LM...

A playbook on postpartum hemorrhage, from prevention to essential management

Reach for the balloon often and, for greatest benefit, apply it early in the postpartum hemorrhage treatment algorithm

Hint: Prioritize a rotational maneuver and delivery of the posterior arm and consider adding manipulation of the posterior axilla to your response...