Impact of obesity. We recently examined the influence of age and obesity on pregnancy outcomes of nulliparous women aged 40 or older at delivery.12 The study included women aged 20 to 29 years (n = 52,249) and 40 or older (n = 1,231) who delivered singleton infants. Women who reported medical disorders, tobacco use, or conception with assisted reproductive technology were excluded.

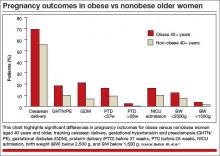

In the older age group (≥40 years), obese women had significantly higher rates of cesarean delivery, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm delivery before 37 weeks’ gestation, and preterm delivery before 28 weeks, and their infants had higher rates of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), compared with nonobese women (FIGURE).

It would appear, however, that healthy, obese women who delay pregnancy until the age of 40 or later may modify their risk for cesarean delivery, gestational diabetes mellitus, and gestational hypertension and preeclampsia by reducing their body mass index to nonobese levels prior to conception.

In addition to maternal risks for women of advanced maternal age, there are risks to the fetus and neonate, as well as a risk of placental abnormalities. These risks are summarized in TABLE 2.

Placental

- Molar or partial molar pregnancy

- Fetus or twins with a complete mole

- Placenta previa, vasa previa

Fetal/neonatal

- Aneuploidy

- Selective fetal growth restriction in twin gestation

- Twin-twin transfusion syndrome

- Preterm birth

- Perinatal death

Antepartum

- Gestational diabetes

- Insulin-dependent diabetes

- Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia

- Cholestasis of pregnancy

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

- Venous thromboembolism

- Preterm labor, preterm premature rupture

of membranes

Intrapartum

- Dysfunctional labor

- Malpresentation

- Cesarean delivery

Postpartum

- Venous thromboembolism

- Postpartum hemorrhage

Folic acid supplementation can reduce some risks

The potential benefit of folic acid supplementation to reduce the risk of fetal open neural tube defects is well documented. More recent data suggest that folic acid also is associated with a reduction in the risks of congenital heart defects, abdominal wall defects, cleft lip and palate, and spontaneous abortion. Supplementation should be initiated at least 3 months prior to conception and continued through the first trimester.

The first trimester

Early pregnancy loss is a risk

Women of advanced maternal age are more likely than younger women to experience early pregnancy loss. This risk is due to higher rates of fetal aneuploidy as well as declining ovarian and uterine function and a higher rate of ectopic pregnancy.

In the First and Second Trimester Evaluation of Risk (FASTER) trial, in which investigators reported pregnancy outcomes by maternal age for 36,056 pregnancies, the rate of spontaneous abortion after 10 weeks of gestation was 0.8% among women younger than 35 years, compared with 2.2% for women aged 40 or older.4

The likelihood of multiple gestation increases

The background risk of multiple births is higher in women of advanced maternal age, compared with younger women. This risk increases further with fertility treatment.

Multiple gestations at any age are associated with increased risks for preterm birth and very-low–birthweight infants. Potential maternal risks are listed in TABLE 3.

- Hypertension (2.5 times the risk of a singleton gestation)

- Abruption (3.0 times the risk)

- Anemia (2.5 times the risk)

- Urinary tract infection (1.5 times the risk)

- Preeclampsia (risk of 26%–75%) (occurs at earlier gestation) — HELLP syndrome (risk of 9%)

- Abruption (20%) (10 times the risk of a singleton gestation)

- Anemia (24%)

- Preterm premature rupture of membranes (24%)

- Gestational diabetes (14%)

- Acute fatty liver (4%) (1 in 10,000 singletons)

- Postpartum hemorrhage (9%)

To reduce the number of multiple gestations with assisted reproduction, consider elective single embryo transfer, especially if the mother has significant underlying medical complications.

Multiple gestations present difficult management issues in older women. Strategies shown to prevent preterm delivery in singleton gestations, including weekly 17-hydroxyprogesterone injections and cervical cerclage, are not effective in multiple gestations. Moreover, many of these therapies—including bed rest—increase the risk of thromboembolic events in multiple gestations, particularly when the mother is of advanced age.

Maternal adaptations in multiple gestations also may be poorly tolerated by older patients, particularly cardiac changes that markedly increase stroke volume, heart rate, cardiac output, and plasma volume.

The range of genetic screening and testing options has broadened

Options include first-trimester CVS, which provides information about the fetal chromosomal complement but not the presence of a fetal open neural tube defect. The procedure-related rate of fetal loss with CVS is quoted as 1%.

Options for genetic testing in the second trimester include transabdominal amniocentesis. A procedure-related fetal loss rate of 1 in 500 to 1 in 1,600 is quoted for midtrimester amniocentesis.