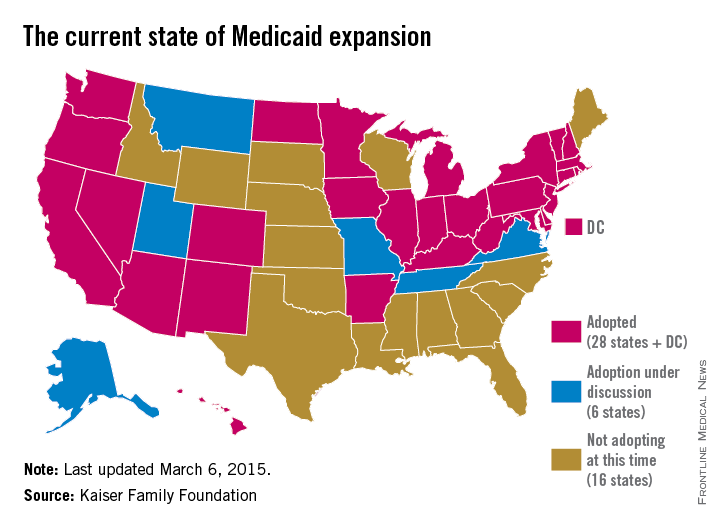

State government officials are getting creative in their efforts to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

After the 2014 election, some states sought to expand their Medicaid programs “with some kind of special arrangement in an attempt to fine tune it to their specific state needs and political objectives,” James F. Blumstein, a constitutional and health law professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, said in an interview. The Republican-controlled Congress is a key reason why, he said. “The Obama [administration] realized if they didn’t make some substantial concessions [in the form of Medicaid waivers] to various local political needs and goals, that those states would not have expanded.”

While at least 12 states chose to expand Medicaid in the 2 years immediately after ACA enactment, others held back.

Debate over the ideal expansion plan – and refusal by some states to expand – is largely based on political views, budget concerns, and resistance to federal programs, Robin Rudowitz, associate director for the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured said during a webinar.

“Some of the states that have opposed have certainly [refused to expand] on ideological grounds,” she said during the presentation. “Some states have cited concerns about cost. Some states are concerned about the federal government’s commitment to maintain the high match.”

So far, six states have earned a federal waiver to create their own brand of Medicaid reform; New Hampshire is the latest. Gov. Maggie Hassan (D) announced on March 5 that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services approved her state’s waiver to expand the New Hampshire Health Protection Program. New Hampshire’s plan implements mandatory qualified health plan (QHP) premium assistance for new patients to purchase coverage. QHPs refer to health plans that are certified by the federal health insurance marketplace, provide essential health benefits, follow established limits on cost-sharing, and meet other federal requirements. New Hampshire’s plan also includes the authority to waive retroactive coverage, a provision that has not been approved in other states.

Expansion waivers approved in Arkansas and Iowa follow similar QHP approaches. Arkansas’s expansion program, approved by CMS through December 2016, allows the state to implement Medicaid expansion through a premium assistance model that uses federal Medicaid funds to purchase coverage through QHPs. Iowa is using the same premium assistance model and also received approval for another option that provides Medicaid coverage through a medical home model for patients with incomes up to 100% of the federal poverty line (FPL) and for medically frail patients up to 138% of the FPL. Meanwhile, Michigan’s alternative program, called Healthy Michigan allows patients to participate in health savings accounts that can be used for required cost-sharing payments. Pennsylvania is transitioning from an approved alternative model to a traditional expansion approach. Former Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Corbett’s (R) Healthy PA program was undone when Gov. Tom Wolf (D) took office. Gov. Wolf plans to move the state to a traditional expansion by Sept. 1.

Indiana’s expansion approach is perhaps the most unique. Similar to other waivers, the state’s plan includes premium assistance and monthly contributions by patients to a personal health savings account. However, unlike other states, Indiana can prevent beneficiaries from reenrolling in coverage for 6 months if they are disenrolled for nonpayment of premiums. The plan also provides a less-generous benefit package to newly eligible beneficiaries at or below the federal poverty level who do not pay premiums. To receive the more generous benefit package, even patients with very little or no income must pay premiums of $1 per month, and medically frail patients above the federal poverty level who do not pay premiums must pay state plan copayments.

Indiana’s expansion encourages personal responsibility by patients, Gov. Mike Pence(R) said in a statement. “We have worked hard to ensure that low-income Hoosiers have access to a health care plan that empowers them to take charge of their health and prepares them to move to private insurance as they improve their lives.”

But constitutional and health law professor David Orentlicher of Indiana University, Indianapolis, said that he believes the expansion may backfire.

“When patients are expected to pay more for their health care, whether through increases in premiums, deductibles, or copayments, they are less able to afford health care,” Mr. Orentlicher said in an interview. “For low-income persons, that can mean not filling prescriptions or seeing a physician when sick. As a result, the health of poor patients may suffer.”

Indiana’s expansion could encourage more states to adopt similar approaches. “It’s important to understand what CMS has approved and what they have said they would deny because these actions set the guideposts and parameters for other states that are considering waiver approaches to implement the expansion,” Ms. Rudowitz said during the webinar.