The introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines 7 (PCV7) and 13 (PCV13) has significantly reduced pneumococcal colonization of the serotypes targeted by the vaccines, but serotypes not covered by these vaccines have picked up the slack, according to an analysis of more than 6,000 young Massachusetts children tested at well child or acute care visits over 15 years.

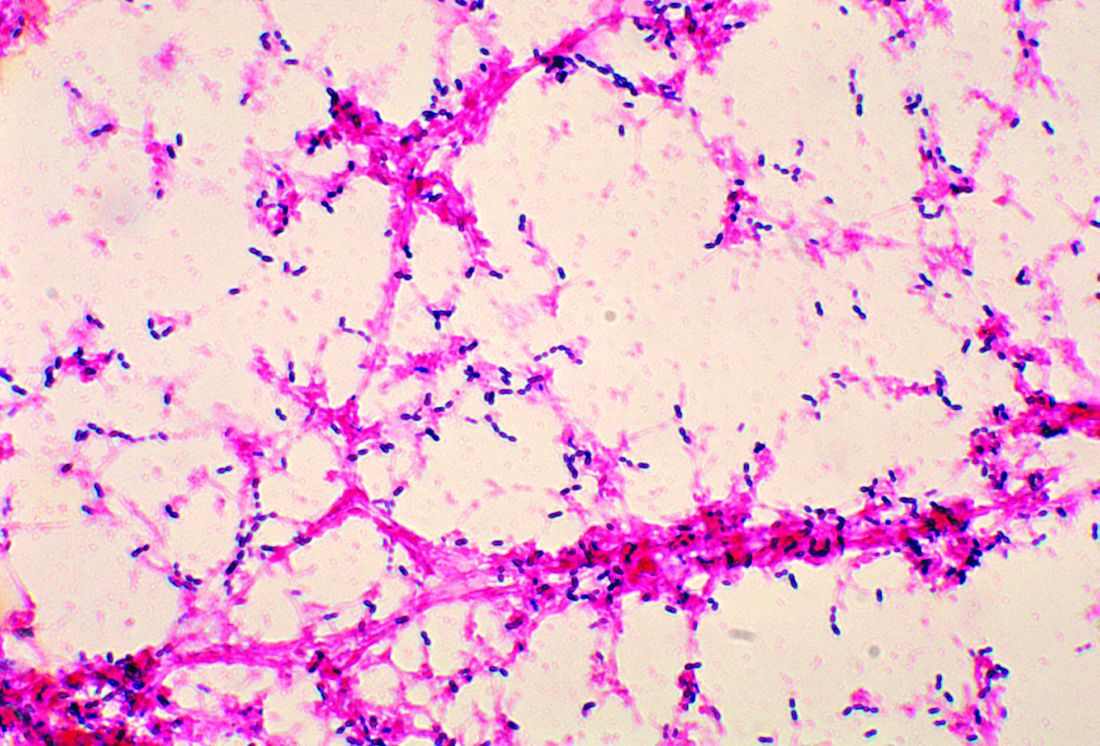

In the past 15 years, use of pneumococcal vaccines in the United States has led to dramatic declines in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in young children, reductions in pneumonia hospitalizations, and herd protection in older adults against disease that otherwise would be caused by the vaccinated serotypes, studies have found. But not all serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae are covered by the vaccines.

The data used in the Massachusetts study included results from nasopharyngeal swabs taken from 6,537 children younger than 7 years of age in various Massachusetts communities during six respiratory illness seasons during 2000-2001, 2003-2004, 2006-2007, 2008-2009, 2010-2011, and 2013-2014. The highest rate of pneumococcal colonization was in 2011 at 32%, and the lowest was in 2004 at 23%, Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, of the Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, both in Boston, and her associates reported (Pediatrics. 2017;140[3]:e20170001).

In 2001, PCV7 serotypes were the most common, but after the rapid introduction of the vaccine, infection rates for those serotypes quickly declined, nearly disappearing by 2007. Serotype 19A became the most common serotype in 2004, but after the introduction of PCV13 in 2010, it and other serotypes targeted by PCV13 also began to decline. In 2014, the most common serotypes were 15B/C, 35B, 23B, 11A, and 23A.

Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for about a third of observed Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizations in 2001, but by 2014 they accounted for nearly all colonizations. In addition, the overall rate of infection did not decrease over the study period. While a reduction was seen from 2011 to 2014, it remains to be seen whether this drop is transient.

“Replacement with nonincluded serotypes remains a risk with vaccines that do not cover the full range of serotype diversity. As new selective pressures are applied, such as the introduction of a vaccine into a community, the void may be filled by nontargeted serotypes,” as was observed after PCV7, Dr. Lee and her fellow researchers noted.

Nonsusceptibility to erythromycin was most common in 2014, with 35% of pneumococcal isolates displaying either moderate susceptibility or resistance. Nonsusceptibility to ceftriaxone (12%), clindamycin (9%), and penicillin (6%) was significantly less common, and no isolates were found to have vancomycin resistance.

“First-line penicillins continue to be the most frequently prescribed antibiotic across all age groups among young children in Massachusetts, which may result in the continued success of 19A associated with penicillin resistance,” the researchers said.

Risk factors associated with colonization by either PCV13 serotypes or non-PCV13 serotypes include younger age, more hours of child care exposure, and having a respiratory tract infection on the day of sampling. The presence of a smoker in the house and recent usage of antibiotics was associated with colonization by PCV13 serotypes but not by non-PCV13 serotypes.

“As newer pneumococcal vaccines are developed, there will continue to be a need for monitoring both the intended and unintended consequences of altering the nasopharyngeal niche through immunization,” Dr. Lee and her associates concluded.

This work was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and the National Institutes of Health. Marc Lipsitch, PhD; William P. Hanage, PhD; Ken Kleinman; Stephen Pelton, MD; and Susan S. Huang, MD, MPH, reported various conflicts of interest. Dr. Lee and the remaining investigators indicated that they had no potential conflicts of interest.