a personal finance website.

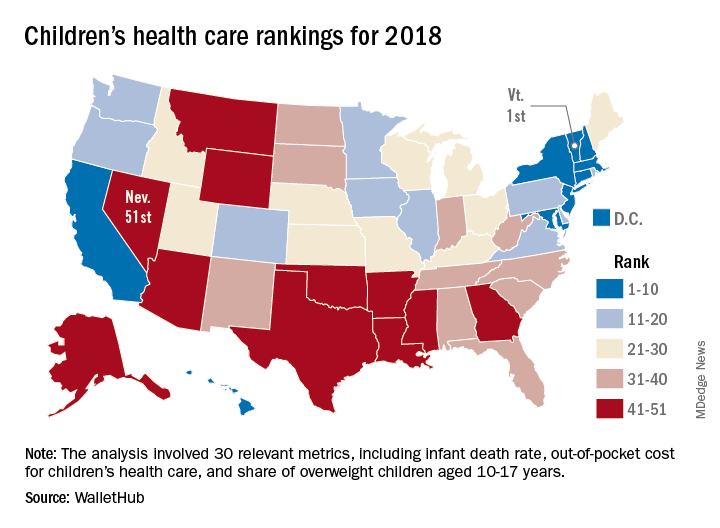

The District of Columbia joined the party and finished second to Vermont, which pushed Nevada down to 51st place, according to WalletHub’s “Best & Worst States for Children’s Health Care” for 2018.

Louisiana’s 50th-ranked health system was just ahead of Nevada’s, and those two were below Texas in 49th, Mississippi in 48th, Arkansas in 47th, and Montana in 46th. The top five had a strong New England flavor (think maple syrup and cranberries), with Vermont joined by Massachusetts in third and Connecticut in fourth, followed by New England’s neighbor New York in fifth, the report showed.

The analysis involved a 100-point system covering three broad areas of health care: health and access to health care (55 points); nutrition, physical activity, and obesity (40 points); and oral health (5 points). Those categories were divided into a total of 30 relevant metrics, including the share of children aged 0-17 years who were in excellent to very good health, pediatricians and family physicians per capita, share of obese children aged 10-17 years, and share of children aged 1-17 years with excellent or very good teeth.

Vermont’s strong showing in WalletHub’s metric system was driven by first-place finishes in lowest infant death rate, pediatricians and family physicians per capita, and percentage of children with recent medical and dental checkups, along with being in third place for percentage of uninsured children and for percentage of overweight children. D.C. had the lowest percentage of children with unaffordable medical bills, and Massachusetts had the lowest percentage of uninsured children, according to data collected by WalletHub from such sources as the U.S. Census Bureau, the Council for Community and Economic research, and the Trust for America’s Health.

“Parents should be supported to learn about and be active in [their] children’s development. … Since our safety net is anemic and our idea of health is about lack of symptoms, this answer challenges us to think more critically about our living conditions and those of our children,” Michael Montoya, PhD, associate professor emeritus in the departments of anthropology, public health, and the program in medical education for the Latino community at the University of California, Irvine, said in the report.

Another respondent to the report, Christina M. Dalton, PhD, of the department of economics at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., said, “Children’s health coverage has important potential to improve health and economic outcomes in the future since early good health enables children to learn better in school. However, any expansion of public options needs to take into account the idea that public insurance can end up taking enrollees away from the private market. … It’s always a trade-off of increasing coverage while not attracting too many of the enrollees that would have already bought insurance without government funding.”