published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

“Although many children with asthma achieve symptom control with appropriate management, a substantial subset does not,” Bradley E. Chipps, MD, from the Capital Allergy & Respiratory Disease Center in Sacramento, Calif., and his colleagues wrote in the recommendations sponsored by the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. “These children should undergo a step-up in care, but when and how to do that is not always straightforward. The Pediatric Asthma Yardstick is a practical resource for starting or adjusting controller therapy based on the options that are currently available for children, from infants to 18 years of age.”

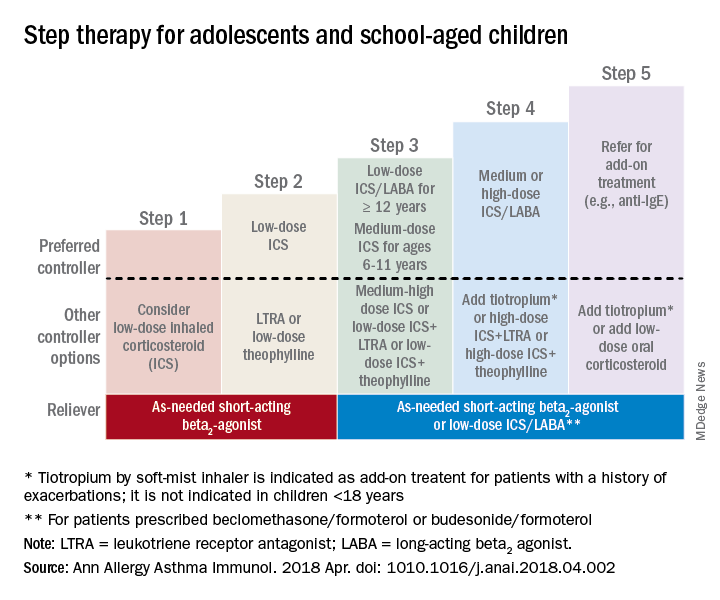

In their recommendations, the authors grouped patients into age ranges of adolescent (12-18 years), school aged (6-11 years), and young children (5 years and under) as well as severity classifications.

Adolescents and school-aged children

For adolescents and school-aged children, step 1 was classified as intermittent asthma that can be controlled with low-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) for as-needed relief. Children considered for stepping up to the next therapy should show symptoms of mild persistent asthma that the authors recommended controlling with low-dose ICS, leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), or low-dose theophylline with as-needed SABA.

In children 12-18 years with moderate persistent asthma (step 3), the authors recommended a combination of low-dose ICA and a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA), while children 6-11 years should receive a medium dose of ICS; other considerations for school-aged children include a medium-high dose of ICS, a low-dose combination of ICS and LTRA, or low-dose ICS together with theophylline.

Adolescent or school-aged children with severe persistent asthma (step 4) should take a medium or high dose of ICS together with LABA, with the authors recommending adding tiotropium to a soft mist inhaler, combination high-dose ICS and LTRA, or a combination high-dose ICS and theophylline.

Dr. Chipps and his coauthors recommended children stepping up therapy beyond severe persistent asthma (step 5) should add on treatment such as low-dose oral corticosteroids, anti-immunoglobulin E therapy, and adding tiotropium to a soft-mist inhaler.

For adolescent and school-aged children going to steps 3-5, Dr. Chipps and his coauthors recommended prescribing as needed a short-acting beta2 agonist or low-dose ICS/LABA.

Children 5 years and younger

In children 5 years and younger, intermittent asthma (step 1) should be considered if the child has infrequent or viral wheezing but few or no symptoms in the interim that can be controlled with as-needed SABA. These young children who show symptoms of mild persistent asthma (step 2) can be treated with daily low-dose ICS, with other controller options of LTRA or intermittent ICS.

Stepping up therapy from mild to moderate persistent asthma (step 3), young children should receive double the daily dose of low-dose ICS from the previous step or use the low-dose ICS together with LTRA; if children show symptoms of severe persistent asthma (step 4), they should continue their daily controller and be referred to a specialist; other considerations for controllers at this step included adding LTRA, adding intermittent ICS, or increasing ICS frequency.