If the name Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is unfamiliar, you haven’t been reading some of the best articles on this website . Dr. Pichichero, an infectious disease specialist at the Research Institute at the Rochester General Hospital in New York, reports in his most recent ID Consult column on new research presented at the June 2019 meeting of the International Society for Otitis Media, including topics such as transtympanic antibiotic delivery, biofilms, probiotics, and biomarkers.

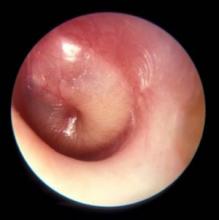

Dr. Pichichero described work he and his colleagues have been doing on the impact of overdiagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM). They found when “validated otoscopists” evaluated children, half as many reached the diagnostic threshold of being labeled “otitis prone” as when community-based pediatricians performed the exams.

Looking around at the colleagues with whom you share patients, do you find that some of them diagnose AOM much more frequently than does the coverage group average? How often do you see a child a day or two after he has been diagnosed with AOM by a colleague and find that the child’s tympanic membranes are transparent and mobile? Do you or your practice group keep track of each provider’s diagnostic tendencies? If these data exists, is there a mechanism for addressing apparent outliers? I suspect that the answer to those last two questions is a firm “No.”

I don’t have the stomach this morning to open those two cans of worms. But certainly Dr. Pichichero’s findings suggest that these are issues that need to be addressed. How the process should proceed in a nonthreatening way is a story for another day. But I’m not sure that involving your community ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist as a resource is the best answer. The scenarios in which pediatricians and ENTs perform otoscopies couldn’t be more different. In the pediatrician’s office, the child is generally sick, feverish, and possibly in pain. In the ENT’s office, the acute process has probably passed and the assessment may lean more heavily on history. The child is more likely to accept the exam without resistance, and the findings are not those of AOM but of a chronic process. The fact that Dr. Pichichero has been able to find and train “validated otoscopists” suggests that improving the quality of otoscopy among the physicians in communities like yours and mine is achievable.

How are your otoscopy skills? Do feel comfortable that you can do a good exam and accurately diagnose AOM? When did you acquire that comfort level? Probably not in medical school. More likely as a house officer when you were guided by a more senior house officer who may nor not been a master otoscopist. How would you rate your training? Or were you self-taught? Do you insufflate? Are you a skilled cerumen extractor? Or do you give up after one attempt? Be honest. How is your equipment? Are the bulbs and batteries fresh? Do you find yourself frustrated by an otoscope that is tethered to the wall charger by a cord that ensnarls you, the parent, and the patient? Have you complained to the practice administrators that your otoscopes are inadequate?

These are not minor issues. It is clear that overdiagnosis of AOM happens. It may occur even more often than Dr. Pichichero suggests, but I doubt it is less. Overdiagnosis can result in overtreatment with antibiotics, and the cascade of consequences both for the patient, the community, and the environment. Overdiagnosis can be the first step on the path to unnecessary surgery. It is incumbent on all of us to make sure that our otoscopy skills and those of our colleagues are sharp, that our equipment is well maintained and that we remain abreast of the latest developments in the diagnosis and treatment of AOM.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.