Not infrequently, less than 90 day old infants have fever and irritability and are more sleepy than usual, but have no apparent focus of infection. The sepsis evaluation is usually negative. It is frustrating for parents and providers when we report that we don’t really know what caused the febrile illness.

In summer/autumn season, some infants have enterovirus, with the predominate serotypes varying year to year. The enterovirus genus has several species, i.e., polio, enterovirus, echovirus, and Coxsackie A and Coxsackie B viruses. Echovirus is an acronym for enteric, cytopathic, human, orphan virus. Coxsackie is named from the city where it was first reported. Recently discovered enteroviruses have numbers starting at 68, and include a strain causing severe disease in Asia, enterovirus 71.

Sometimes clinicians can tell that enterovirus is in the community without laboratory tests because children present with hand, foot, and mouth (and sometimes buttock) disease. or herpangina. Enteroviruses also cause pericarditis, myocarditis, or pleurodynia (a.k.a. the "devil’s grippe").

But enteroviruses also cause aseptic meningitis. A modest pleocytosis with a mononuclear predominance and near-normal CSF glucose/protein values, plus negative bacterial cultures, is commonly called "aseptic meningitis."

Enteroviruses cause modest CSF pleocytosis (50-400 WBC), usually with mononuclear predominance and relatively normal CSF chemistries. While there can initially be a CSF neutrophil predominance, the differential usually shifts to mostly mononuclear cells less than 24 hours later. In the 1970s and 1980s (before polymerase chain reaction [PCR]), we used a "double tap" strategy to allow early discontinuation of antibiotics and hospital discharge. If the second CSF obtained within 24 hours of the first CSF had reasonably normal chemistries plus fewer WBCs or shifted to almost all mononuclear cells, children were discharged before final culture results. While hypoglycorrhachia is seen rarely with enterovirus (as low as 10 mg/dL), low CSF glucose values are usually due to bacterial or tuberculous meningitis. CSF protein concentrations with enteroviral meningitis are rarely greater than 80 mg/dL, the usual values for bacterial meningitis.

But consider this caveat: When "aseptic meningitis" seems present but CSF chemistries are abnormal (elevated protein or low glucose), check for tuberculosis risk factors and/or indolent neurological findings that could indicate tuberculous meningitis. In infants less than 2 months of age, consider neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) disease, particularly if the CSF protein is elevated.

These days "double taps" are not routine. Instead, CSF PCR is used. HSV and enterovirus PCR on CSF is available at most institutions with results available before bacteria cultures are final. A positive CSF enterovirus PCR (J. Pediatr. 1997;131:393-7) allows discontinuing antibacterials and acyclovir, if it was started empirically, plus early discharge. A positive HSV PCR also clarifies management: Continue acyclovir but discontinue antibacterial drugs. Keep in mind that enteroviral meningitis outbreaks are quite seasonal, with the majority of disease noted in the summer and early fall.

So we know the answer if the enterovirus or HSV PCR is positive. But what if these PCRs and bacterial cultures are negative in a child not pretreated with antibiotics? Well, the new kid on the block for aseptic meningitis is human parechovirus (HPeV). The first viruses classified as HPeV (HPeV1 and HPeV2) were previously called echovirus 22 and echovirus 23. But clinical and genome differences from enteroviruses led to reclassification as HPeVs. Now there are 16 HPeV serotypes. So why do we care?

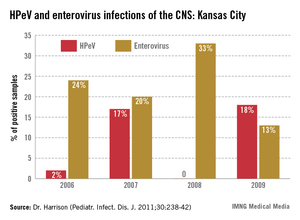

In the past 6 years, HPeV3 emerged as the most common definable cause of sepsis-like syndrome in young infants with negative bacterial cultures (J. Clin. Virol. 2011;52:187-91; Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2013;32:213-6). Interestingly, HPeV3-infected infants have more frequent peripheral leukopenia and lymphopenia plus more febrile days and higher fevers than those with enteroviruses. HPeV3 has a nearly every-other-year cycle (May-November). HPeV was as frequent or more frequent than all enteroviruses combined.

HPEV is not detected by enterovirus PCR, but is confirmed by HPeV-specific PCR. Like enteroviruses, PCR of blood is usually positive in HPeV-infected infants.

An important difference from HSV or enteroviruses is that almost no HPeV3 CNS-infected infants have CSF pleocytosis. That’s right. CSF in HPeV CNS infection is like HHV-6 (minimal CSF WBCs despite CNS infection). At our institution, HPeV3 PCR is performed routinely on CSF from all infants less than 90 days of age undergoing sepsis evaluations in summer/autumn.

If cultures and PCRs are negative in young infants with sepsis-like syndrome, your laboratory can likely perform or send out HPeV3 PCR. When HPeV3 CSF PCRs are positive, antibacterials can be stopped and patients discharged. Clinicians may be reluctant to discharge before final negative bacterial cultures because these infants can still "look ill," and providers are just learning about HPeV3. But based on our multiyear experience, it appears safe. We saw only three concurrent bacterial infections when HPeV3 was detected in CSF – all urinary tract infections that were easily detected during the sepsis evaluation and treated as such.