Posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is a relatively common procedure. However, intestinal obstruction is a possible complication in the case of an asthenic adolescent with weight loss after surgery. We present the case of a 12-year-old girl who underwent an uncomplicated posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation for scoliosis and who developed nausea, emesis, and abdominal pain. We also discuss the origins, epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), a rare condition. The patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

The patient was a 12-year-old girl with juvenile idiopathic scoliosis. She was seen by a pediatric orthopedist at age 8 after her primary care physician noticed a curve in her back during her physical examination. Given her age and primary curve of 25º, magnetic resonance imaging was ordered, which was negative for syrinx, tethered cord, or bony abnormalities. An underarm thoracolumbosacral orthosis (Boston Brace) was prescribed to be worn 23 hours/day. There was inconsistent follow-up over the next 4 years, and her curve progressed to 55º (right thoracic) and 47º in the lumbar spine (Figures 1, 2). Given the magnitude of the curves, surgical intervention was recommended, because bracing would no longer be beneficial.

The patient was healthy and appeared vibrant with no medical issues. She weighed 49 kg and her height was 162 cm (body mass index [BMI], 18.6; normal). She underwent segmental posterior spinal instrumentation, and a fusion was performed from T4 to L4 using a cobalt chrome rod. Postoperatively, there were no problems. Her diet was slowly advanced from clear liquids to regular food over 3 days. She was discharged on postoperative day 4. She had no abdominal distention, pain, or nausea. The family was instructed about pain medication (oxycodone liquid, 5 mg every 4 hours as needed) and how to prevent and treat constipation.

Three days after discharge, her mother called to inquire about positioning because the patient was uncomfortable owing to back pain. There were no abdominal complaints, and she was taking her pain medicine every 4 hours. She was instructed to lie in a comfortable position and to ambulate several times daily. The patient took little food or fluids because of a lack of appetite and back pain. On postoperative day 8, she presented to the emergency department with complaints of generalized abdominal pain and 1 day’s emesis. The patient had not had a bowel movement postoperatively. An acute abdominal series (AAS) was obtained (Figure 3), which noted a nonobstructive bowel gas pattern, with some increased colonic fecal retention. The patient was given intravenous (IV) fluids and an IV anti-emetic, and was admitted for observation. The pediatric surgical team evaluated her and concluded her symptoms resulted from constipation. Her symptoms improved over 2 to 3 days, and she had several bowel movements on day 2 after taking polyethylene glycol, sennosides, and bisacodyl suppositories. At discharge, she was noted to be passing gas, and her abdominal examination revealed no tenderness or guarding. She had mild distention, but it had improved from the previous day. She ate breakfast and ambulated several times. She had no complaints of abdominal pain and was released home with her parents. Staff reiterated instructions regarding constipation, diet, and follow-up. Her discharge weight was 48 kg (down 1 kg) and her BMI was 17.2 (down 1.4; underweight). Her height was now 165 cm (up 3 cm). Postoperative radiographs noted stable fixation with corrected curves (Figures 4, 5).

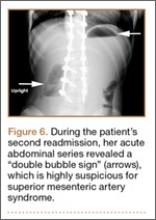

At home, the patient ate little but continued to drink fluids. On postdischarge day 3, she developed nausea, bilious emesis, and generalized abdominal pain. She returned to the emergency department. At this point, the patient weighed 44.5 kg (down 6.6 kg since the initial surgery) and her BMI was 16.1 (down 2.5; underweight). She was admitted, and IV fluids were initiated. She had more than 1300 mL of bilious emesis. A nasogastric (NG) tube was inserted. Initial laboratory findings were unremarkable other than an increase in serum lipase of 261 U/L. Her amylase level was within normal limits. An AAS was again completed and showed a distended stomach and loop of small bowel below the liver with an air fluid level. There were also distended loops of bowel in the pelvis (Figure 6).

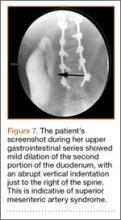

A pediatric surgical consultant examined her the next morning. An upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) was obtained and showed air fluid levels in the stomach with prompt gastric emptying into a normal caliber duodenal bulb. However, with supine positioning, there was significant dilatation of the second portion of the duodenum with abrupt vertical cutoff just to the right of the spine, compatible with SMAS (Figure 7). There was reflux of contrast material into the stomach from the duodenum, with no passage of barium into the distal duodenum. After the UGI, a nasojejunal (NJ) feeding tube was placed. The tip was left at the beginning of the fourth part of the duodenum. Repeated attempts to pass the NJ feeding tube beyond the fourth part of the duodenum were unsuccessful because of massive gastric distention. The patient was taken to the operating room for placement of a Stamm gastrostomy feeding tube with insertion of a transgastric jejunal (G-J) feeding tube under fluoroscopy (Figure 5). The patient had the G-J feeding tube in place for 6 weeks to augment her enteral nutrition. As she gained weight, her duodenal emptying improved. She gradually transitioned to normal oral intake. She has done well since the G-J feeding tube was removed.