In children, pelvic fractures are uncommon, with an incidence ranging from 1% to 4.6% of all pediatric fractures,1-4 and acetabular fractures make up only 0.8% to 15% of pelvic fractures.1,3,5,6 Acetabular fractures are so uncommon in children partly because of the cartilaginous nature of the immature acetabulum. The increased cartilage volume relative to adults provides greater capacity for energy absorption, resulting in greater elastic and plastic deformation before fracture occurrence. More force is therefore required to cause a fracture, and associated visceral injuries, head injuries, and long-bone fractures are common.3,7,8

The impact of acetabular fractures on adolescents warrants special attention because any resulting disability will affect them during their most productive years. Both avascular necrosis (AVN) and degenerative arthritis are particularly devastating complications in this age group. Complications such as premature physeal closure9-15 are unique to adolescents, and there is little information available on how injury in older children affects growth in this area.

There have been very few studies of the outcomes of these injuries in children. Mostly, there have been case reports and small series primarily dealing with nonoperative management of acetabular fractures in adolescents.3,10,11,16-20 By contrast, operative treatment of acetabular fractures in adults has been well described, and outcomes widely reported. As a result, much of our knowledge about managing these injuries is extrapolated from the adult literature. Although treatment of acetabular fractures in adults has evolved substantially, treatment of these injuries in adolescents remains primarily nonoperative. We conducted a study to evaluate outcomes of treatment of adolescent acetabular fractures.

Patients and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of all adolescent patients admitted with a diagnosis of acetabular fracture to 2 academic institutions between 1991 and 2003. Thirty-eight patients (28 males, 10 females) were identified. Mean age at time of injury was 15 years (range, 11-18 years). Mean follow-up was 3.2 years (range, 5-180 months).

Data on fracture types, treatment methods, associated injuries, complications, union rates, pain, and return to normal activities were collected. Acetabular fractures were classified according to the system of Letournel and Judet.21 There were 20 elementary and 18 associated fractures.

Of the 38 patients, 30 sustained high-energy trauma in motor vehicle accidents (25) or in falls from significant heights (5). The other 8 patients injured themselves playing sports (4 had severe traumatic brain injury, 2 had labial wounds, and 2 had injuries involving the abdominal viscera). Twelve patients had associated pelvic ring injuries, 18 had femoral head dislocations, 2 had femoral head fractures, and 13 had evidence of impaction injury to the femoral head articular cartilage. Twelve patients had marginal impaction of the acetabular wall. Fifteen patients had open triradiate physes at time of injury (Table 1).

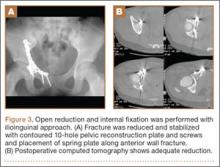

Thirty-seven of the 38 patients were treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) by an experienced orthopedic trauma surgeon; 1 patient with a stable posterior wall fracture was treated nonoperatively. Surgical indications were articular displacement of more than 1 mm, hip joint instability, irreducible hip dislocation, and intra-articular fracture fragments. In the 37 surgically treated cases, the approaches used were Kocher-Langenbeck (22), ilioinguinal (8), combined Kocher-Langenbeck/ilioinguinal (5), and triradiate (2).

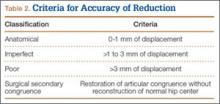

Immediate postoperative radiographs were evaluated by 3 orthopedic surgeons blinded to the patients’ clinical outcomes. Displacement was evaluated on anteroposterior (AP) and Judet views of the pelvis, as described by Matta,22 and reductions were classified as anatomical (0-1 mm of displacement), imperfect (>1 to 3 mm), poor (>3 mm), or surgical secondary congruence (Table 2).

Results

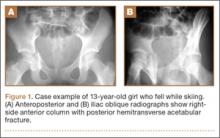

Thirty-seven patients underwent acetabular fracture ORIF. Immediate postoperative radiographs showed 30 anatomical reductions and 7 imperfect reductions. One patient had surgical secondary congruence and developed AVN of the hip. We could not identify an association between the quality of the reduction and the outcome with respect to pain or return to activity. However, no patient had a poor reduction. An illustrative case is presented in Figures 1 to 4.

All acetabular fractures united within 4.5 months (range, 3.0-8.0 months) after the index procedure. Early postoperative complications included 3 cases of meralgia paresthetica and 13 cases of abductor weakness. Meralgia paresthetica resolved spontaneously in all 3 patients. Of the 13 patients with abductor weakness, 11 improved with physical therapy, 1 was limited by the head injury, and 1 subsequently underwent hip fusion. One patient had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) that was identified before surgery and managed with warfarin.

Other complications included 1 case of deep infection of the surgical wound. This infection presented 4 months after surgery and was treated with débridement, hardware removal, and a 3-month course of antibiotics. Two patients who sustained hip dislocations at time of injury developed AVN of the femoral head. Both developed osteoarthritis, and 1 underwent hip fusion. Eight patients developed heterotopic ossification on the side of the acetabular fracture; 4 of them underwent surgical excision. Four patients required a separate operation for hardware removal. Four patients with triradiate cartilage involvement went on to premature closure. No patient had any leg-length discrepancy or dysplasia at time of follow-up.