Case 4

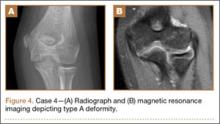

A 10-year-old girl sustained a Gartland type III supracondylar humerus fracture treated with closed reduction and pinning at an outside facility. She experienced full return to function postoperatively until developing stiffness and popping 1 year after surgery. She was evaluated at our institution 5 years postoperatively with elbow popping in full extension. Radiographs showed a type A deformity; MRI confirmed the diagnosis of AVN of the humerus (Figure 4). She underwent elbow arthroscopy with débridement of a posterior cartilage flap and synovial band. After elbow arthroscopy and débridement, she had resolution of symptoms with full elbow ROM.

Case 5

A 5-year-old boy sustained a Gartland III supracondylar humerus fracture that was treated with closed reduction and pinning at our institution. He had full return of painless motion postoperatively. Seven years after surgery, he presented with popping sensation in his elbow. Examination showed a 5º lack of full extension without effusion or crepitus. Radiographs showed a type A deformity with dissolution of the lateral ossification center (Figure 5).

Discussion

Avascular necrosis of the trochlea after supracondylar humerus fractures was first reported by McDonnell and Wilson in 1948.2 Four of 53 patients (7.5%) developed AVN of the trochlea. Clinical presentation happened at 2 to 7 years after injury. No causative effect was given; however, 2 cases of AVN were associated with narrowing of joint space and thinning of articular cartilage. One incident was associated with multiple reduction attempts.2 The etiology and exact incidence remain unclear, but both vascular insult and idiopathic growth disturbance have been proposed.4

Morrissy and Wilkins5 in 1984 reported 3 cases of dissolution of the trochlea after supracondylar humerus fractures: 1 fracture was casted, 1 was splinted, and 1 underwent closed reduction and pinning. Radiographic abnormality was noted at 5 years, 1 year, and 9 months, respectively. These authors explained the dissolution as a vascular phenomenon. Interruption of the medial or lateral vessels supplying the cartilage of the trochlea would lead to the central necrosis pattern seen in their 3 cases. In addition, the rapid onset in Morrissy and Wilkin’s second and third cases (both 7 years old) supports a vascular etiology.5

A more recent study of 6 cases found dissolution of the trochlea occurred as a result of severe displaced supracondylar fractures.6 Four of the 6 cases involved nerve injuries. Evidence of fishtail deformity was delayed from fracture time until 7 to 8 years of age, consistent with the ossification of the trochlea. Additionally, MRI findings, as well as loose body formation, added to the plausibility of AVN.6

Haraldsson7 demonstrated the 2 main sources of blood supply to the medial crista of the trochlea. The lateral vessels are intra-articular and supply the apex and lateral aspect of the trochlea. The medial vessels supply the medial aspect of the medial crista of the trochlea and are extra-articular. The lateral and medial vessels do not have an anastomosis between them (Figure 6).7 Disruption of the lateral vessels results in a type A deformity; disruption of the lateral and medial vessels results in a type B deformity. Displaced supracondylar humerus fractures disrupt the periosteum and can result in disruption of the medial and/or lateral vessels, resulting in AVN and deformity.

Another case of AVN of the trochlea after a Gartland type I fracture was reported by Schulte and Ramseier.8 Similar to our case 3, the patient developed type A AVN of the distal humerus,9 illustrating an interruption of the lateral, intra-articular vessels. The etiology of vascular disruption in these nondisplaced supracondylar humerus fractures is less clear, but we propose that tamponade may play a role. Nondisplaced fractures result in a fracture hematoma contained in an intact capsule, having the potential to increase pressures and lead to occlusion of the lateral, intra-articular vessels. This would result in a type A deformity. Nondisplaced supracondylar humerus fractures are common, and this complication is very rare. Typically, they would be expected to generate modest fracture hematoma. However, patient factors, such as bleeding disorders or anatomic variants, including a constricted capsule, could predispose patients to development of increased intracapsular pressure. In contrast, Gartland type II and III fractures, although higher-energy, presumably tear the surrounding capsule leading to release of the fracture hematoma. We do not have direct evidence to support this theory, but measurement of intracapsular pressures could help support or refute the occurrence of tamponade. Similar studies have been reported in hip fracture and slipped capital femoral epiphysis, in which hematoma has been shown to increase intracapsular pressure.8,10 This pressure increase can theoretically cause a tamponade of the femoral head blood supply leading to AVN. Additional alternate explanations for AVN of the trochlea after type I fractures may include a rare occurrence of direct trauma to the vessels at the moment of fracture, increased intracapsular pressure from cast positioning, or that they are unrelated events that occurred in the same elbow (because atraumatic AVN has also been reported).