CHICAGO – Patients receiving the LINX magnetic sphincter device for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) at a community hospital have outcomes comparable with those achieved at the best academic centers, a study suggests.

“This is a safe and effective operation that, importantly, is very reproducible in the community setting,” Dr. F. Paul “Tripp” Buckley III said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. “Unlike a Nissen [fundoplication] where you have to have 50 [surgeries completed] to be considered an expert and then do over 35 a year to continue to have great outcomes, this is a highly teachable event and can be employed out in the community with little hesitation.”

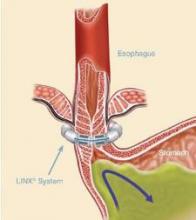

The magnetic sphincter augmentation device (LINX, Torax Medical) was approved in the United States in 2012 for the treatment of GERD and consists of a series of interlinked titanium-encased magnets implanted laparoscopically around the esophagus. The magnets augment a weak lower esophageal sphincter and avoid some of the complications of fundoplication, said Dr. Buckley, who disclosed serving as a proctor and speaker for Torax.

In the 5-year study leading to its approval, 64% of patients achieved the primary outcome of normalization of esophageal acid exposure or at least a 50% reduction in exposure at 1 year after sphincter augmentation and 93% of patients cut their use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) by at least 50%. Six serious adverse events occurred (N Engl J Med. 2013;368:719-27).

Dr. Buckley, of Scott & White Health in Round Rock, Tex., and his associates evaluated their first 102 patients undergoing magnetic sphincter augmentation under general anesthesia at two community hospitals. GERD health-related quality of life (GERD-HRQL) scores were compared before and after surgery and overall results were compared with the clinical trial data. The highest possible total GERD-HRQL score is 75 (worst symptoms) and lowest score 0 (no symptoms).

The community and clinical trial cohorts were similar in age (median, 54 vs. 53 years), sex (both 52% male), median body mass index (both 28 kg/m2), and PPI use (98% vs. 100%), which was a requirement for trial entry.

After patients in the community underwent magnetic sphincter augmentation, PPI use decreased from 98% to 8%, median GERD-HRQL scores declined from 27 to 5, and patient satisfaction with GERD rose from 8% to 84%, which fell short of the satisfaction rate in the clinical trial (84% vs. 94%; P = .05), Dr. Buckley said.

The reduction in PPI use, however, was similar with that reported in the clinical trial, as was the percentage achieving at least 50% improvement in GERD-HRQL scores (86% vs. 92%), and operative times (median 49 vs. 36 minutes), he noted.

Device removal was rare at 1% in the community vs. 6% in the trial (P = .06).

Lower rates of dilation were noted in the community (9% vs. 19%; P = .04), perhaps because of refinements in technique and postoperative management, Dr. Buckley said.

“We know with this device you have to eat normally after implantation so that it will open and close within the scar capsule that’s naturally going to form,” he noted. “You have some patients that scar very tightly and you’ve got other patients that have a little bit of pain with eating and then suddenly they’re back on a liquid diet, which is a death knell for the success of this operation. So you really have to talk with these patients. I tell folks, ‘This is not a fix-it-and-forget-it type of operation.’ You’re going to get to know these patients pretty well, particularly in the early postoperative period.”

Final results recently reported with 5 years of follow-up in the clinical trial showed that 85% of patients were free from daily dependence on PPIs, heartburn was reduced from 89% to 12%, and moderate or severe regurgitation declined from 57% to 1.2%. No migrations or malfunctions occurred (J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015 Oct;25[10]:787-92).

“One key aspect of this operation, and we think one of the reasons for its success and lack of migrations of the device, is that we keep the phrenoesophogeal ligament intact, so you are never in the mediastinum,” Dr. Buckley said. “For those of us who do a lot of Nissens, you end up blowing through it every time. But here when you keep it intact, you can roll it up on the distal esophagus and you can really reduce the hiatal hernia pretty significantly, even pretty large ones.”