A bone island is a focus of normal cortical bone located within the medullary cavity. The vast majority of bone islands are small, measuring from 1 mm to 2 cm in size. They are found more frequently in adults than in children. The lesion can be virtually diagnosed on the basis of its characteristic clinical and imaging features. Differential diagnosis may be difficult when the lesion manifests itself uncharacteristically by being symptomatic, very large, and hot on bone scan.1-4

The term giant bone island has been used to describe a large lesion1 that measures more than 2 cm in any dimension.5 Giant bone islands have been described only in adults,1,5-15 and the longest bone island length reported is 10.5 cm.10 They are usually symptomatic and associated with increased radionuclide uptake on bone scintigraphy.14

The history and the clinical and imaging presentation of an even longer, symptomatic, and scintigraphically hot lesion in the tibial diaphysis of a 10-year-old boy is reported. The lesion further exhibited several atypical imaging features necessitating an open biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of a giant bone island. The pertinent differential diagnosis and the clinical and radiographic findings after 15-year follow-up are also presented and discussed. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

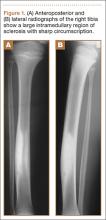

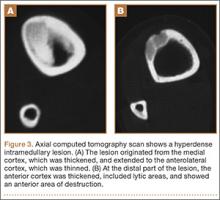

A 10-year-old boy was admitted for surgical repair of an inguinal hernia. Physical examination revealed a painless but tender anterior bowing of the right tibial diaphysis. The patient was a healthy-appearing white male with normal vital signs, gait, and posture. His parents noticed a slight protuberance of the tibia at age 2.5 years. No medical advice was asked for the bone swelling after that time. After recovery from the inguinal hernia repair 3 weeks later, the bone lesion was thoroughly examined. Radiographs showed an oblong, homogenous region of dense sclerosis in the diaphysis of the right tibia. The lesion had relatively well-defined margins and was located in the medullary cavity. Speculations were not obvious in the periphery of the lesion, which exhibited a sharp circumscription (Figures 1A, 1B). A well-defined lytic area was evident at the distal part of the lesion (Figure 1B). There was no periosteal reaction. Blood and serum chemistries were within normal limits, including serum calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase. A conventional 3-phase bone scintigraphy (300 MBq) with technetium-99m HDP (hydroxydiphosphonate) indicated increased uptake in the area of the lesion but no other skeletal abnormality (Figure 2). Computed tomography (CT) showed that the lesion was purely intramedullary and densely blastic. The lesion originated from the medial cortex, which was thickened (Figure 3A). The lesion extended to the anterolateral cortex, which was thinned and included a lytic area. In the distal part of the lesion, the anterolateral cortex was thickened, included lytic areas, and exhibited an anterior portion of cortical destruction (Figure 3B). The fatty marrow adjacent to the region of sclerosis appeared normal. There was no evidence of extraosseous soft-tissue changes. On both T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lesion exhibited low-signal intensity. The lesion measured 10.8×2.2×1 cm. It originated from the medial cortical bone of the tibia, blended into the medullary cavity, and extended anteriorly towards and through the anterior cortex. The area of cortical destruction was clearly evident on the axial MRI. The periosteum was displaced and eroded anteriorly by focal radiating bony streaks. No enhancement was seen after the intravenous administration of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) as a contrast medium. There were no extraosseous soft-tissue changes. In the distal part of the lesion, sagittal and axial MRI showed a 1.2×0.8×0.7-cm well-defined ovoid focus, with characteristics of cystic degeneration that exhibited intermediate-signal intensity on T1-weighted MRI (Figure 4) and high-signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI.

An open biopsy was performed. Macroscopically, a wedge of compact bone measuring 3×1.7×0.6 cm was taken. Microscopic examination showed a thinned periphery of lamellar (mature) bone with haversian canals and, beneath it, woven (immature) bone with long-surface processes projecting within adjacent cancellous bone (Figure 5A). The woven bone contained loose vascular fibrous tissue. No osteoclasts were noted, and the very few osteoblasts lining the bone trabeculae were small, single-layered, and flat (Figure 5B). There was no evidence of neoplastic cells. There was no abnormality of the periosteum and the surrounding soft tissues.

The histology was pathognomonic of a giant bone island. No additional surgical intervention was recommended.

The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged 2 weeks later. An above-the-knee plaster was recommended for 3 months and a below-the-knee splint for an additional 2-month period. Full weight-bearing was allowed only after the postsurgical sixth month to prevent an impending fracture. The tibial bowing was tender to pressure or palpation, and the patient reported mild spontaneous pain during follow-up. Radiographs 1 year after surgery indicated that the bone area removed for biopsy was replaced by compact bone. MRI performed 4 years after surgery showed that the volume of the lesion in relation to the host bone was not changed.