Musculoskeletal disorders, the leading cause of disability in the United States,1 account for more than half of all persons reporting missing a workday because of a medical condition.2 Shoulder disorders in particular play a significant role in the burden of musculoskeletal disorders and cost of care. In 2008, 18.9 million adults (8.2% of the US adult population) reported chronic shoulder pain.1 Among shoulder disorders, rotator cuff pathology is the most common cause of shoulder-related disability found by orthopedic surgeons.3 Rotator cuff surgery (RCS) is one of the most commonly performed orthopedic surgical procedures, and surgery volume is on the rise. One study found a 141% increase in rotator cuff repairs between the years 1996 (~41 per 100,000 population) and 2006 (~98 per 100,000 population).4

US health care costs are also increasing. In 2011, $2.7 trillion was spent on health care, representing 17.9% of the national gross domestic product (GDP). According to projections, costs will rise to $4.6 trillion by 2020.5 In particular, as patients continue to live longer and remain more active into their later years, the costs of treating and managing musculoskeletal disorders become more important from a public policy standpoint. In 2006, the cost of treating musculoskeletal disorders alone was $576 billion, representing 4.5% of that year’s GDP.2

Paramount in this era of rising costs is the idea of maximizing the value of health care dollars. Health care economists Porter and Teisberg6 defined value as patient health outcomes achieved per dollar of cost expended in a care cycle (diagnosis, treatment, ongoing management) for a particular disease or disorder. For proper management of value, outcomes and costs for an entire cycle of care must be determined. From a practical standpoint, this first requires determining the true cost of a care cycle—dollars spent on personnel, equipment, materials, and other resources required to deliver a particular service—rather than the amount charged or reimbursed for providing the service in question.7

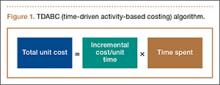

Kaplan and Anderson8,9 described the TDABC (time-driven activity-based costing) algorithm for calculating the cost of delivering a service based on 2 parameters: unit cost of a particular resource, and time required to supply it. These parameters apply to material costs and labor costs. In the medical setting, the TDABC algorithm can be applied by defining a care delivery value chain for each aspect of patient care and then multiplying incremental cost per unit time by time required to deliver that resource (Figure 1). Tabulating the overall unit cost for each resource then yields the overall cost of the care cycle. Clinical outcomes data can then be determined and used to calculate overall value for the patient care cycle.

In the study reported here, we used the TDABC algorithm to calculate the direct financial costs of surgical treatment of rotator cuff tears confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in an academic medical center.

Methods

Per our institution’s Office for the Protection of Research Subjects, institutional review board (IRB) approval is required only for projects using “human subjects” as defined by federal policy. In the present study, no private information could be identified, and all data were obtained from hospital billing records without intervention or interaction with individual patients. Accordingly, IRB approval was deemed unnecessary for our economic cost analysis.

Billing records of a single academic fellowship-trained sports surgeon were reviewed to identify patients who underwent primary repair of an MRI-confirmed rotator cuff tear between April 1, 2009, and July 31, 2012. Patients who had undergone prior shoulder surgery of any type were excluded from the study. Operative reports were reviewed, and exact surgical procedures performed were noted. The operating surgeon selected the specific repair techniques, including single- or double-row repair, with emphasis on restoring footprint coverage and avoiding overtensioning.

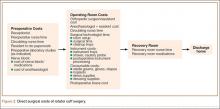

All surgeries were performed in an outpatient surgical center owned and operated by the surgeon’s home university. Surgeries were performed by the attending physician assisted by a senior orthopedic resident. The RCS care cycle was divided into 3 phases (Figure 2):

1. Preoperative. Patient’s interaction with receptionist in surgery center, time with preoperative nurse and circulating nurse in preoperative area, resident check-in time, and time placing preoperative nerve block and consumable materials used during block placement.

2. Operative. Time in operating room with surgical team for RCS, consumable materials used during surgery (eg, anchors, shavers, drapes), anesthetic medications, shoulder abduction pillow placed on completion of surgery, and cost of instrument processing.

3. Postoperative. Time in postoperative recovery area with recovery room nursing staff.

Time in each portion of the care cycle was directly observed and tabulated by hospital volunteers in the surgery center. Institutional billing data were used to identify material resources consumed, and the actual cost paid by the hospital for these resources was obtained from internal records. Mean hourly salary data and standard benefit rates were obtained for surgery center staff. Attending physician salary was extrapolated from published mean market salary data for academic physicians and mean hours worked,10,11 and resident physician costs were tabulated from publically available institutional payroll data and average resident work hours at our institution. These cost data and times were then used to tabulate total cost for the RCS care cycle using the TDABC algorithm.