Ulnar nerve injury leads to clawing of the ulnar digits and loss of digital abduction and adduction because of paralysis of the ulnar innervated extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. Isolated motor paralysis without sensory deficit can occur from compression within the Guyon canal.1 Cubital tunnel at the elbow is the most common site for ulnar nerve compression.2 Compression at both levels can be encountered in sports-related activities. Nerve compression in the Guyon canal can occur with bicycling and is known as cyclist’s palsy,3-6 but it can also develop from canoeing.7 Cubital tunnel syndrome is the most common neuropathy of the elbow among throwing athletes, especially in baseball pitchers and can result from nerve traction and compression within the fibro-osseous tunnel or subluxation out of the tunnel.2 Both compression syndromes can develop from repetitive stress and/or pressure to the nerve in the retrocondylar groove.

Ulnar nerve palsy may be associated with forearm fractures, which is usually caused by simultaneous ulna and radius fractures, especially in children.8-12 To our knowledge, there are no reports in the literature of an ulnar nerve palsy associated with an isolated ulnar shaft fracture in an adult. We report a case of delayed ulnar nerve palsy after an ulnar shaft fracture in a baseball player. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 19-year-old, right hand–dominant college baseball player was batting right-handed in an intrasquad scrimmage when a high and inside pitched ball from a right-handed pitcher struck the volar-ulnar aspect of his right forearm. Examination in the training room and emergency department revealed moderate swelling and ecchymosis over the distal third of the ulna. He had a normal neurovascular examination, including normal sensation to light touch and normal finger abduction/adduction and wrist flexion/extension. He was otherwise healthy. Radiographs of the right forearm showed a minimally displaced transverse fracture of the distal third of the ulna (Figures 1A, 1B).

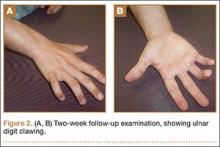

The patient was initially treated with a well-padded, removable, long-arm posterior splint for 2 weeks with serial examinations each day in the training room. At 2-week follow-up, he reported less pain and swelling but stated that his hand had “felt funny” the past several days. Examination revealed clawing of the ulnar digits with paresthesias in the ulnar nerve distribution (Figures 2A, 2B). His extrinsic muscle function was normal. Radiographs showed stable fracture alignment. Ulnar neuropathy was diagnosed, and treatment was observation with a plan for electromyography (EMG) at 6 weeks after injury if there were no signs of nerve recovery. Physical therapy was instituted and focused on improving intrinsic muscle and proprioceptive functions with the goal of an expeditious, but safe, return to playing baseball. Three weeks after his injury, the patient had decreased tenderness at his fracture site and was given a forearm pad and sleeve for light, noncontact baseball activity (Figure 3). A long velcro wrist splint was used during conditioning and when not playing baseball. Forearm supination and pronation were limited initially because of patient discomfort and to prevent torsional fracture displacement or delayed healing. Six weeks after his injury, the patient returned to hitting and was showing early signs of improved sensation and intrinsic hand strength. He had progressed to a light throwing program and reported difficult hand coordination, poor ball control, and overall difficulty in accurately throwing over the next 3 to 4 months. Because of his difficulty with ball control, the patient began a progressive return to full-game activity over 6 weeks, which initially included a return to batting only, then playing in the outfield, and, eventually, a return to his normal position in the infield. Serial radiographs continued to show good fracture alignment with appropriate new bone formation (Figures 4A, 4B). Normal motor strength was noted at 3 months after injury and normal sensation at 4 months after injury.

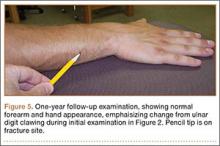

By the end of his summer league, 6 months after his injury, the patient was named Most Valuable Player and had a batting average over .400. He reported near-normal hand function. One year after injury, his examination revealed normal hand function (Figure 5), including normal sensation to light touch, 5/5 intrinsic hand function, and symmetric grip strength. Radiographs showed a healed fracture (Figures 6A, 6B). The patient has gone on to play more than 9 years of professional baseball.

Discussion

The ulnar nerve has a course that runs down the volar compartment of the distal forearm. The flexor carpi ulnaris provides coverage to the nerve in this area. Proximal to the wrist, the nerve emerges from under the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and passes deep to the flexor retinaculum, which is the distal extension of the antebrachial fascia and blends distally into the palmar carpal ligament.13 In our patient, the most likely cause of this presentation of ulnar neuropathy was the direct blow to the nerve from the high-intensity impact of a thrown baseball to this superficial and exposed area of the forearm. Since the patient presented with delayed paresthesias and ulnar clawing 2 weeks after injury, possible contributing causes could be evolving pressure or nerve damage from a perineural hematoma and/or intraneural hematoma or increased local pressure from intramuscular hemorrhage.14 There are both acute and chronic cases of ulnar nerve entrapment by bone or scar tissue that resolved by surgical decompression.8-12 Surgical exploration was not deemed necessary in our case because the fracture was minimally displaced, and the patient regained sensation and motor function over the course of 3 to 4 months.