Statistical Methods

The data compiled was then analyzed with SAS/STAT Software (SAS Institute Inc.) and a LR Type III analysis using the GENMOD procedure. The method of analysis and presentation of data focuses on the relationship between respondents perceptions between the surgeon-peer and naïve subject groups. The P values presented are the significance of the testing of interactions comparing the difference between surgeon-peers and naïve subjects, and the differences in their responses to each question for self-promoters and non-self-promoters. Surgeon-peers answer questions differently based on their assessment of a self-promoter or non-self-promoter website. It is this difference that is compared to the analogous difference for naïve subjects and statistically evaluated. The LR statistic for type III analysis tests if the differences are significantly different, ie, if the difference between the 2 subject groups is statistically significant. All statistical methods were performed by a qualified statistician who helped guide the design of this study.

Results

Each respondent was asked if they were aware that misinformation about doctors exists on the Internet. Half of the naïve subjects affirmed awareness of this whereas the other half were unaware. All surgeon-peers were aware of the presence of misinformation regarding physicians on the Internet.

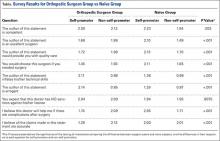

The results of the comparisons are shown in the Table. The columns show the average response to each question for self-promoters and non-self-promoters grouped by either surgeon-peer or naïve subject. In judging the overall accuracy of statements made on the Internet, naïve subjects found no difference between self-promoters and non-self-promoters, whereas surgeon-peers judged the difference to be large and significant in favor of non-self-promoting surgeons. Surgeon-peers generally rated non-self-promoters with significantly more positive Likert scores, indicating improved “competence”, “excellence”, and “better quality of care” when compared to naïve respondents (Table). The direction and magnitude of the difference was also striking, with the naïve respondents favoring self-promoters on all of these questions. This held true for the choice of orthopedic surgeon, where naïve responders favored self-promoters and surgeon-peers favored non-self-promoters. Moreover, naïve subjects believed that self-promoters would be significantly more likely to help them in the event of a complication, whereas surgeon-peers believed the opposite. Even when the direction of difference was the same in both groups, statistically significant differences in the responses were evident, as was the case when respondents were asked “Did the surgeon inflate his/her technical skills?” or “Did the author of this statement seem arrogant?” Both groups favored self-promoters for these questions, but the differences were larger among surgeon-peers, indicating that naïve subjects were somewhat less sensitive to the differences between promoters and non-self-promoters. There was no difference between surgeon-peers and naïve subjects in their expectations of sanctions against self-promoters’ licenses when compared to non-self-promoters, which was the only question to fail to garner a significant difference between respondents.

Discussion

This study explores the differences in the perceptions of physician websites between board-certified orthopedic surgeons and naïve individuals. These websites contain varying amounts of information presented in numerous ways. While we did not poll the website authors regarding their intent, the purpose of a website seems naturally to communicate believable information to the public. The information provided ranges widely from basic facts regarding education and contact information to statements regarding technical skills, reputation, television appearances, and the friendly nature of the office staff.

Our results suggest that board-certified orthopedic surgeons, peers of the writers of these websites, tend to view self-promoting surgeons more negatively than do their nonphysician counterparts. These findings support our hypothesis that self-promoting surgeons are perceived more favorably by the naïve, nonphysician population.

At first glance, our results suggest that the mere absence of a surgeon from the medium may affect the patient’s choice, because 50% of our naïve respondents indicated that they would use the Internet to choose a doctor. Interestingly, both the surgeon-peer group and naïve subjects were equally aware that misinformation exists on the Internet. However, when reviewing the websites, naïve subjects were significantly more likely to view self-promoters as more competent, more excellent, and more likely to provide quality care, and were more likely to choose the self-promoter if they needed surgery compared to the surgeon-peer group. The naïve group viewed self-promoters as less likely to inflate their technical skills but more likely to be arrogant. They viewed self-promoters as more likely to help if things went wrong and more likely to make accurate statements compared to the surgeon-peer group. This suggests that patients with little experience are more likely to choose a self-promoting physician than one who does not self-promote for reasons that cannot be proven true or false in the confines of a website. Further study is needed to see if perceptions based on web content translate into actual changes in healthcare choices.