Case 3

A 78-year-old woman, nonsmoker, presented with a 1-year history of left buttock and thigh pain exacerbated by ambulation. Ambulation was limited to 2 blocks. The patient was being worked up for spinal and hip etiologies of pain at an outside hospital. MRI revealed a mild posterior disc herniation at L3/4 and L4/5 and moderate narrowing of the spinal canal. She underwent 2 epidural steroid injections with no improvement. The patient’s relative, a physician, suggested that the patient receive a vascular surgery consultation, and the patient ultimately presented to our institution for evaluation by vascular surgery.

The physical examination was significant for a 1+ dorsal pedis pulse on the left compared to 2+ on the right. Moreover, the patient only demonstrated trace L femoral pulse compared to the right. Strength was 5/5 bilaterally.

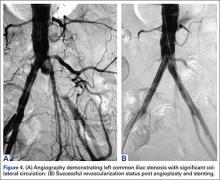

The patient was taken to the operating room for angioplasty and stenting of the left common iliac artery (Figures 4A, 4B). This provided immediate symptom relief, and she has remained asymptomatic.

Discussion

Lumbar radiculopathy is a common diagnosis encountered by orthopedic surgeons. Although the diagnosis can appear to be straightforward in a patient presenting with lower back and leg pain, the etiology of lower back and leg pain can be extremely varied, and can be musculoskeletal, neurologic, vascular, rheumatologic, or oncologic in origin.1 In particular, differentiating between radiculopathy and vascular claudication can sometimes be challenging.

The 2 most common causes of lumbar radiculopathy are lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis.1 Lumbar disc herniation results from tear in the annulus of the intervertebral disc, resulting in herniation of disc material into the spinal canal causing compression and irritation of spinal nerve roots.1 Spinal stenosis is narrowing of the spinal canal that produces compression of neural elements before they exit the neural foramen.3 Adult degenerative spinal stenosis is most often caused by osteophytes from the facet joints or hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum, and can be broadly categorized into central spinal stenosis or lateral spinal stenosis.

PAD is defined as progressive stenosis or occlusion, or aneurysmal dilation of noncoronary arteries.2 When PAD affects the vessels of the lower extremities, the symptoms typically manifest as intermittent claudication, which is exercise-induced ischemic pain in the lower extremity that is relieved by rest.2 As the disease progresses, symptoms can progress to rest pain, ulceration, and, eventually, gangrene. The most common cause of PAD is atherosclerosis, and the risk factors include smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The prevalence of PAD rises sharply with age, starting from <3% in ages less than 60 years to >20% in ages 75 years and older.4

A detailed and pertinent history from the patient provides important information for differentiating radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication from vascular claudication. Patients with lumbar radiculopathy typically report pain in the lower back radiating down the leg past the knee in a dermatomal distribution. The pain often begins soon if not immediately after activity, but often takes time for relief onset after rest. Positional changes in the back such as flexion can provide relief.2 Patients with neurogenic claudication from central spinal stenosis can present with bilateral thigh pain from prolonged standing and activity that is alleviated with flexion or stooping.3 Patients may admit to a positive “shopping cart sign,” with increased walking comfort stooped forward with hands on a shopping cart.

In contrast, patients with vascular claudication often report pain in the calf, thigh, or hip, but rarely in the foot. The location of pain varies with area of stenosis; generally, patients with superficial femoral artery occlusion present with calf claudication, while patients with aortoiliac disease present with buttock and thigh pain. The pain typically occurs after a very reproducible length of walking, and is relieved by cessation of walking, often even if the patient remains standing. Back positioning should have no effect on the pain.2-5

Physical examination should begin with observation of the patient’s gait and posture, which may be hunched over in the setting of spinal stenosis. Examination of the patient’s skin may show loss of hair, shiny skin, or atrophic changes suggestive of vascular disease (Figure 5).1 Prior to proceeding to a spine examination, palpating the trochanteric bursa and testing for hip range of motion is important to rule out intra-articular hip pathology and trochanteric bursitis as common causes of pain in the area. Patients with radiculopathy may show sensory disturbances in a dermatomal distribution, muscular weakness at the corresponding spinal level, and decreased deep tendon reflexes. The straight leg raise test can elicit signs of nerve root tension. A careful examination of bilateral lower extremity pulses at the dorsal pedis, popliteal, and femoral levels can help identify any asymmetric or decreased pulses that would indicate peripheral vascular disease. With chronic aortoiliac disease, it is important to check for femoral pulses, given the dorsal pedis pulse can be present due to collateral circulation. And finally, the ankle brachial index (ABI), measured as the ratio of the systolic pressure at the ankle divided by the systolic pressure at the arm, is a good screening test for PAD.6 A normal ABI is >1.

A thorough history and physical examination can elicit important information that is helpful in evaluating orthopedic patients, especially to differentiate between spinal and vascular causes of leg pain. This can help avoid misdiagnoses, which result in unnecessary tests, procedures, and wasted time. Don’t forget the pulses!