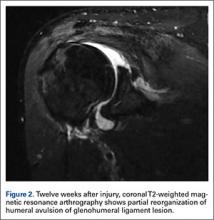

Ten weeks after injury, clinical inspection revealed deltoid wasting. Active shoulder ROM was limited, and deltoid strength was 3/5, though the patient was able to perform a standard push-up without difficulty and showed no sign of laxity or apprehension on shoulder examination. Repeat EMG testing revealed axillary nerve denervation with no sign of regeneration. Twelve weeks after injury, MRA showed reorganization and partial healing of the HAGL lesion relative to the prior study (Figure 2).

On the patient’s return from training, 15 weeks after injury, he had improved active ROM and 4+/5 deltoid strength. Axillary nerve sensation was still decreased but markedly improved. Physical examination revealed no significant shoulder laxity or apprehension, and the patient denied feelings of instability. Activities were advanced to include an organized strengthening program.

Six months after injury, the patient was cleared to return to his unit with only mild physical restriction. Function continued to steadily improve. After 9 months, he was cleared for full, unrestricted duty. Although he still demonstrated slight asymmetric weakness in the right deltoid with continued muscular atrophy, examination findings were otherwise normal, and he was back to full activities without significant symptoms.

Eleven months after injury, MRI showed healing of the HAGL lesion (Figure 3). At 17 months, EMG testing revealed significant interval improvement in axillary motor unit potentials but still about a 50% decrement compared with the noninjured side. The patient denied any motor or sensory deficits and any instability events since his injury. He continued with full function as an active-duty Navy SEAL.

Discussion

Nonoperative management has been used for injuries to the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex when there is no humeral detachment but generally has been reserved for low-demand patients and patients who cannot tolerate surgical intervention.4 Detached lesions may initially be managed nonoperatively with physical therapy and rehabilitation, but the rate of recurrent instability after nonoperative management of a known HAGL lesion remains unknown.4 Most active young people are expected to have persistent pain and/or instability and require surgical intervention. Both arthroscopic and open methods have been used successfully.3,8-15 Persistent instability is often the primary complaint leading to a diagnosis of a HAGL lesion.4 The patient in this case report neither demonstrated nor reported any instability event after his 6-month period of nonoperative management, despite his young age and elite physical requirements.

To our knowledge, there are no reports of successful nonoperative management of a known symptomatic HAGL lesion in a high-demand athlete. Although we do not routinely recommend nonoperative treatment for cases such as the one reported here, the decision to delay this Navy SEAL’s surgical management was made out of concern about potential complications of postoperative rehabilitation given the concurrent axillary nerve injury.

With anterior shoulder dislocations, multiple concomitant shoulder injuries, including a HAGL lesion, are not uncommon.6,16 With HAGL lesions, associated rotator cuff injuries occur at a rate as high as 23%.6 Our patient had a concurrent partial rotator cuff tear but also an axillary nerve traction injury. To our knowledge, the literature has not described axillary nerve injury specifically in association with a HAGL lesion, though it is well documented and maintained as a possible concurrent injury with anterior shoulder instability events.17 Robinson and colleagues16 found a 5.8% incidence of a clinically apparent neurologic deficit after traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation in 3633 dislocations, about 75% of which were isolated axillary nerve injuries. They also reported a 25.7% rate of rotator cuff tear or greater tuberosity fracture, either of which significantly increased the likelihood of a neurologic deficit in their study.