There is a paucity of literature on how mechanism of injury may be associated with patient retention. Failure to attend outpatient clinics is a form of noncompliance and a major obstacle to safe, effective, and efficient healthcare delivery. Noncompliance may lead to increased patient morbidity and carries substantial financial implications for the healthcare system.1,2 In addition to these direct patient and healthcare issues, loss of patient follow-up or the belief of potential loss of follow-up of penetrating trauma patients may also significantly affect research studies. These patients often may be excluded from studies, even if they might otherwise meet inclusion criteria, because of concerns that they are unlikely to follow-up after leaving hospital. Is this myth or fact? To validate or to disprove this selection bias, we conducted a study in which we retrospectively evaluated long bone fractures caused by either penetrating or blunt trauma.

Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we used the trauma database of an American College of Surgeons–verified level I trauma center in a major Midwest metropolitan area to compile a list of all cases of long bone fractures caused by penetrating trauma between 2006 and 2009 (N = 132). Gunshot wounds were the mechanism of injury for the penetrating trauma. We also compiled a list of control cases—long bone fractures caused by blunt trauma in patients demographically matched to the penetrating group patients on sex, race, and age (N = 104) (Table).

The mechanisms of blunt trauma included motor vehicle collisions, pedestrians struck by vehicles, falls, altercations, and crush injuries.We retrospectively performed chart reviews to obtain patient follow-up data 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after injury from penetrating or blunt trauma. Patients scheduled to return on an as-needed basis were considered to have completed follow-up. The 2 groups were also statistically compared with respect to sex, race, age, surgical fixation, and history of tobacco, alcohol, or drug use.

SAS/STAT Version 8 (SAS Institute) was used to test the equality of survival functions (patient retention) for the penetrating and blunt trauma patient groups. A similar comparison was made for the categories of sex, race, and age. Pearson χ2 test was used to compare the 12-month survival rates of the 2 treatment groups across sex and race. Binary logistic regression was used to compare the 12-month survival rates of the 2 treatment groups removing the effect of age. A comparison of the frequency distributions of the 2 treatment groups with respect to alcohol use, tobacco use, drug use, and surgical intervention was also performed. Power analysis showed power of more than 90% in detecting at least a 20% difference in the follow-up rates between the penetrating and blunt trauma groups based on our sample size.

Results

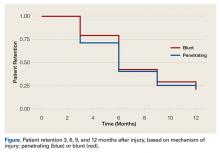

There was no statistically significant difference (P = .736) between the penetrating and blunt trauma patients in terms of follow-up within 1 year after injury. At 1 year, 103 (78%) of the 132 penetrating trauma patients and 83 (80%) of the 104 blunt trauma patients were lost to follow-up (Figure).

There was no statistically significant difference in the follow-up rates for sex (P = .12), race (P = .96), or age (P = .37). There was no statistically significant difference between the penetrating and blunt trauma groups with respect to sex (P = .54), race (P = .28), age (P = .18), tobacco use (P = .13), or alcohol use (P = .06). Of the 132 patients in the penetrating trauma group, 50 were African American men in their 20s. This demographic makes up 38% of all patients in the penetrating trauma group. The database of blunt trauma long bone fractures was used to demographically match the penetrating trauma group. The blunt trauma database had 1003 patients, from which 104 were matched to the penetrating trauma group. When matches were sought for the African American men in their 20s, only 21 were found in the blunt trauma database, and they were used (Table). There was a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups with respect to drug use (P = .02), with a higher prevalence in the penetrating trauma group (30.3% vs 17.31%). There was also a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups with respect to surgical fixation (P = .003), with a higher rate of surgery in the blunt trauma group (89% vs 75%). The blunt trauma group was demographically matched to the penetrating trauma group with the underlying criterion being long bone fracture. The specific long bone injury was not matched between the 2 groups. Evaluation of the data showed a higher percentage of upper extremity fractures in the penetrating trauma group (38%) than in the blunt trauma group (29%). On further inspection, we found that 21% of the penetrating trauma group had humerus fractures, for which only 48% underwent surgery. In comparison, only 5.8% of the blunt trauma group had humerus fractures, for which 83% underwent surgery. This variation in long bone distribution between the 2 groups explains our finding a higher propensity for surgical fixation in the blunt trauma group (89%) compared with the penetrating trauma group (75%).