Total hip arthroplasty (THA) has revolutionized the practice of orthopedic surgery. The number of primary THAs performed in the United States alone is predicted to rise to 572,000 per year by 2030.1 Increasing demand requires a tighter focus on cost-effectiveness, particularly with regard to expensive postoperative complications. Trunnionosis and taper corrosion have recently emerged as problems in THA.2-7 No longer restricted to metal-on-metal bearings, these phenomena now affect an increasing number of metal-on-polyethylene THAs and are exacerbated by modularity.8 The emergence of these complications adds complexity to the diagnostic algorithm in patients who present with painful THAs. Furthermore, the diagnosis of either trunnionosis or taper corrosion calls for revision surgery. In response to the increase in these complications, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm for managing suspected metal toxicity issues.9 However, increases in toxicity and patient morbidity, and the added costs of toxicity surveillance and revision surgery, will place a substantial economic burden on many health systems at a time when policy makers are implementing substantial changes to health delivery in an effort to contain costs while improving patient outcomes.

Although they are more expensive than cobalt-chrome heads, ceramic femoral heads make metal toxicity a nonissue and eliminate the need for toxicity surveillance protocols. Furthermore, ceramic femoral heads are thought to have longevity advantages (this relationship needs to be confirmed in long-term studies).

In this article, we provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic femoral heads in all THA patients could represent a more cost-effective option over the long term.

Materials and Methods

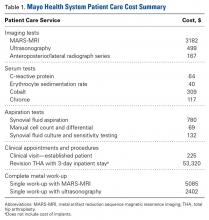

Guidelines for the diagnostic algorithm for painful THA with suspected metal toxicity were obtained from a recent orthopedic professional society consensus statement.9 The cost of this work-up was obtained from the finance department at our institution (Table 1).

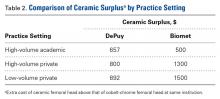

All costs are uniform across our health system, from rural primary care clinics to tertiary referral centers. The aspects of clinical care analyzed in this study included imaging tests (metal artifact reduction sequence magnetic resonance imaging [MARS-MRI], ultrasonography [US], radiography); serum tests (C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, cobalt, chrome); aspiration tests (synovial fluid aspiration, manual cell count and differential, synovial fluid culture and sensitivity testing); clinical appointments and procedures (established patient visit, revision THA with 3-day inpatient stay) (Table 1).We created 2 metrics to analyze the cost difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads. The first metric was “ceramic surplus,” the extra cost of a ceramic femoral head above that of a cobalt-chrome femoral head, and the second was “maximum ceramic surplus,” the ceramic surplus cutoff value for which using ceramic femoral heads in all patients becomes more cost-effective than using cobalt-chrome heads.

Ceramic surplus was determined for 3 different practice settings (high-volume academic, high-volume private, low-volume private) using data from 2 implant companies (DePuy, Biomet) (Table 2).The cost of a metal work-up was determined for a single round of imaging tests (stratified by MRI and US), serum tests, aspiration tests, and clinic visit. These data were then combined with the cost of revision THA (Table 1) to create a series of maximum ceramic surplus models. In all these simulations, we assumed that about 7% of patients with metal-on-polyethylene THA would present with groin pain 1 to 2 years after surgery,10 and, working on this assumption, we applied a series of theoretical incidence ratios (12.5%, 25%, 50%) to both the percentage of patients who presented with a painful THA and received a metal toxicity work-up and the percentage of those who received the toxicity work-up and eventually needed revision surgery. For example, in the best-case scenario, the model assumes that 7% of THA patients present with pain and that 12.5% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (0.875% of all THAs). The best-case scenario then assumes that 12.5% of patients who receive a work-up for metal toxicity are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). By contrast, in the worst-case scenario, the model continues to assume that 7% of THA patients present with pain, but it also assumes that 50% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (3.5% of all THAs).

The worst-case scenario then assumes that 50% of patients who receive a work-up for metal toxicity are eventually revised (1.75% of all THAs). As preferences and availability for 3-dimensional imaging differ between centers, the models were stratified by use of MARS-MRI or US. The resulting number in all the simulations was the maximum ceramic surplus (Table 3).The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values were calculated from the best-case scenario, and the highest from the worst-case scenario. These steps were taken in keeping with the fact that a lower incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions would require the price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome heads (ceramic surplus) to be small in order for ceramic heads in all patients to be cost-effective. The inverse is true for a high incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions: A larger price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads would be tolerable to still be cost-effective.