Case Report

In January 2013, a 17-year-old male soccer player suffered an ACL rupture of his right knee. Later that spring, he had an ACL reconstruction with an allograft. Twelve months postoperatively, the patient returned, saying that he felt much better; however, anytime he tried to plant his foot and rotate over that fixed foot, his knee felt unstable. The physical examination revealed both negative Lachman and anterior drawer tests but a I+ pivot shift test. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination revealed an intact ACL graft. A diagnostic ultrasound evaluation revealed a distal ALL injury. After discussing the risks, benefits, and goals with the patient, we opted for a diagnostic arthroscopy and a percutaneous, ultrasound-guided reconstruction of the ALL.

Postoperatively, the patient did very well. One week after surgery, he returned, saying he felt completely stable and demonstrated by repeating the rotation of his knee. The patient continued to have no issues until he returned 13 months post-ALL surgery, complaining of a recent injury that had caused the return of his feelings of instability. An MRI evaluation showed an intact ACL graft and the possibility of a ruptured ALL. Fifteen months after the initial ALL reconstruction, we proceeded with surgery. At arthroscopy, the patient was found to have a pivot shift of I+ and an intact ACL graft. The ALL was reconstructed again using an allograft, internal brace, and bone marrow concentrate. At 13 months post-ALL reconstruction revision, the patient had no complaints.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the ALL is aimed to restore anatomic rotational kinematics. Sonnery-Cottet and colleagues14 have reported promising initial results in their 2-year follow-up study of combined ACL and ALL reconstruction outcomes. This surgical technique includes use of an internal brace, which negates the necessity for external support devices and allows for earlier mobilization of the joint. A reconstruction of the ALL, performed concurrently with the ACL, does not add recovery time, but could prevent postsurgical complications and improve rehabilitation by eliminating rotational instability that presents in some ACL-reconstructed patients.

Sonnery-Cottet and colleagues15 state that their arthroscopic identification of the ALL can help to cultivate a “less invasive and more anatomic” reconstruction. The use of musculoskeletal ultrasound allows our technique to utilize a completely noninvasive imaging tool that allows proper establishment of ALL anatomy prior to the procedure. The entirety of the ALL is easily identifiable,4,12 which has proven to be shortcoming of MRI evaluation.15-17 Accurate preoperative assessment of the lateral structures is necessary in ACL-deficient individuals.11,15 Sonography also provides a means of accurate guidance and socket creation, without generating large incisions.

If the ALL is responsible for internal rotatory stability as asserted, the structure should exhibit biomechanical properties during movement. In their study on the function of the ligament, Parsons and colleagues9 established the inverse relationship between the ALL and ACL during internal rotation. As their cadaveric knees were subjected to an internal rotatory force through increasing angles of flexion, the contribution of the ALL towards stability significantly increased while the ACL declined. Helito and colleagues8 and Zens and colleagues10 have demonstrated length changes of the ligament through varying degrees of flexion and internal rotation. Their reports indicate greater tension during knee movements, coinciding with the description of increasing ALL stability contribution by Parsons and colleagues.9 Kennedy and colleagues7 conducted a pull-to-failure test on the ALL. The average failure load was 175 N with a stiffness of 20 N/mm, illustrating the structure is a candidate for most traditional soft tissue grafts. The biomechanical evidence of the structural properties of the ALL confirms its importance in knee function and the necessity for its reconstruction.

With the understanding that ACL contributes to rotatory stability to some extent, the notion begs the question of how a centrally located ligament is able to prevent excessive rotation in a structure with a large relative radius. Biomechanically, with such a small moment arm, the ACL would experience tremendous stress when a rotatory force is applied. The same torque applied to a more superficial structure, with a greater moment, would sustain a large reduction in the applied force. The concept of a wheel and an axle should be considered. The equation is F1 × R1 = F2 × R2. We measured on a cadaveric knee the distance from the center of rotation to the ACL and the ALL, finding the radii were 5 mm and 30 mm, respectively. Taking these measurements, we would then expect the force experienced on the axle (ACL) to be 6 times greater than what would be experienced on the periphery of the wheel (ALL). The ALL (wheel) has a significant biomechanical advantage over the ACL (axle) in controlling and enduring internal rotatory forces of the knee. This would imply that if the ALL were damaged and not re-established, the ACL would experience a 6 times greater force trying to control internal rotation, which would result in a significantly increased chance of failure and rupture.

While there is a degree of dissent on the presence of the ALL, a number of studies have classified the tissue as an independent ligamentous structure.3-7 While there is disagreement on the precise location of the femoral attachment, there is a consensus on the location of the tibial and meniscal attachments. Claes and colleagues4 originally outlined the femoral attachment as anterior and distal to the origin of the fibular collateral ligament (FCL), which is the description this technique follows. Since Claes and colleagues’4 report, many have investigated the ligament’s femoral origin with delineations ranging from posterior and proximal3,5,7 to anterior and distal.6,16-18

The accurate, noninvasive nature of the musculoskeletal ultrasound prior to any incisions being made makes this technique innovative and superior to other open surgical techniques or those that require fluoroscopy.

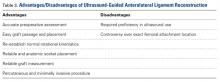

This is the greatest advantage of the procedure (Table 3). Not only does the use of ultrasound make this specific operation exceptional, but its practice is widely applicable. To date, this is the only ultrasound-guided reconstruction of any kind and can serve as a template for not only ALL procedures, but many other procedures as well.