Healing after rotator cuff repair (RCR) can be challenging, especially in cases of large and massive tears, revision repairs, and tendons with poor tissue quality.1-3 Poor tissue quality is associated with increased risk for recurrent tears, independent of age and tear size.3 Various techniques have been used to improve tendon fixation strength in these difficult situations, including augmented suture configurations (eg, massive cuff stitches, rip-stop stitches) and tissue grafts (eg, acellular dermal matrix).4-9 Clinical studies have found improved healing rates for larger tears and revision repairs using acellular dermal matrix grafts.6,10 Synthetic patches are another option for RCR augmentation, but limited clinical data and biomechanical evidence support use of synthetic grafts as an augment for RCRs.11-13

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are a class of biodegradable polymers that have been used as orthopedic devices, tissue scaffolds, patches, and other applications with increasing frequency over the past decade.14 In the laboratory, these implanted materials have been shown to support cell migration and growth.15 The PHA family of polymers typically degrades by hydrolytic and bacterial depolymerase mechanisms over 52-plus weeks in vivo.14PHA grafts have been studied in the setting of RCR. An expanded polytetrafluoroethylene scaffold was shown to improve repair mechanics when used as a bursal side graft in an in vitro ovine model.11 The graft increased tendon footprint contact pressure and failure loads by almost 180 N. In clinical studies, poly-L-lactic acid augmentations have been used to reinforce massive RCRs. Lenart and colleagues16 found that 38% of 16 patients with such tears had an intact rotator cuff at 1.2-year follow-up, and improvement in clinical scores. Proctor13 reported on use of a poly-L-lactic acid retrograde patch for reinforcement of massive tears with both single- and double-row repairs in 18 patients. The cohort had more favorable rates of intact cuffs at 12 months (83%) and 42 months (78%), and ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons) scores improved from 25 before surgery to 82 at latest follow-up after surgery.

RCR augmentation traditionally has been performed with an open or mini-open technique.6 Recently, several authors have reported on arthroscopic techniques for augmentation with either acellular dermal matrix or synthetic grafts.13,17,18 Most techniques have involved “bridging” with a graft or patch used to stress-shield a single-row repair.8,9,13 This bridging typically involves placing several sutures medial to where the anchor repair stitches pass through the tendon. An alternative is to pass the repair stitches through both the tendon and the graft.17-19 The overall volume of tissue incorporated into the repair stitches (rotator cuff plus graft) is increased with the augmented technique relative to the bridging technique. Both can be technically challenging, but the augmented technique may be easier to perform arthroscopically.9,19 Regardless, these techniques are complicated and require a higher level of arthroscopic skills compared with those required in arthroscopic RCR without a graft. Simplifying arthroscopic graft augmentation likely will increase its utility because, even for skilled surgeons, adding a graft can increase operative time by 20 to 30 minutes. Simplification will also extend use of the technique to surgeons with less experience and proficiency with arthroscopic repair.

We developed a simple method for augmenting single-row RCR with a strip of bioresorbable soft-tissue scaffold. We also conducted a study to evaluate the initial biomechanical properties of single-row RCR in cadaveric shoulder specimens augmented with PHA mesh (BioFiber; Tornier) graft as compared with single-row RCR without augmentation. Both cyclic gap formation and ultimate failure loads and displacement were quantified. We hypothesized that the augmented RCRs would have decreased gap formation and increased ultimate failure loads compared with nonaugmented RCRs. This study was exempt from having to obtain Institutional Review Board approval.

Methods

Eight pairs of fresh-frozen cadaver humeri (6 male, 2 female; mean [SD] age, 61 [9] years) were dissected of all soft tissue (except rotator cuff) by Dr. Tashjian, a board-certified, fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeon. There were no qualitative differences in tendon condition between tendons within a pair. The supraspinatus muscle and tendon were separated from the other rotator cuff muscles. The infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor were removed from the humerus. Last, the supraspinatus was resected at its insertion. Humeral pairs were then randomized into augmented and nonaugmented RCRs within each pair.

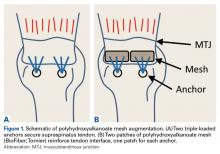

In the nonaugmented group, the supraspinatus was reattached to its insertion in a single-row RCR with 2 triple-loaded suture anchors (5.5-mm Insite FT Ti, No. 2 Force Fiber suture; Tornier) and 6 simple stitches (Figure 1A). Anchors were placed midway between the articular margin and the lateral edge of the greater tuberosity at about 45° to the bone surface.

Anchors were separated by 15 mm, with the anterior anchor 5 mm posterior to the biceps groove. Stitches were passed through the supraspinatus tendon, taking a 15-mm bite of tissue, with each stitch separated by 5 mm. Each suture was then tied with a Revo knot.In the contralateral shoulders, augmented RCRs were performed. Specimens were prepared exactly as they were for the nonaugmented RCRs, including anchor placement and suture passage. Before knot tying, RCRs were augmented with 2 strips of 13-mm × 23-mm PHA mesh (BioFiber) (Figure 1B). One strip was used to augment the 3 sutures of each anchor, overlying the residual tendon, to reinforce the tendon–knot interface. After each suture was passed through the supraspinatus tendon from the intra-articular surface, the stitch was passed through the strip of PHA mesh. Stitches were separated by 5 mm in each mesh strip. All 6 sutures were then tied with a Revo knot between the free end of each suture leg and the leg that passed through the tendon and mesh.

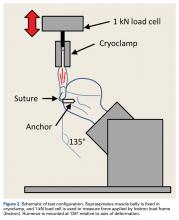

Each humerus was transected at the midshaft and potted and mounted in an Instron 1331 load frame with Model 8800 controller (Instron). A cryoclamp was used to grasp the supraspinatus muscle belly above the musculotendinous junction (Figure 2).

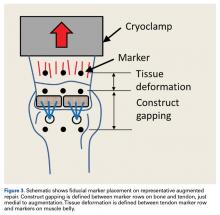

The humerus was aligned in the mounting fixture such that loading was performed at a 135° angle with the humeral shaft (Figure 2).20 The Instron, which was equipped with a 1-kN load cell (Dynacell Model 2527-130; Instron) to monitor applied force, measured applied displacement.Three rows of 2-mm fiducial markers were affixed to the bone, tendon, and muscle belly with cyanoacrylate for tracking with a digital video system (DMAS Version 6.5; Spicatek) (Figure 3).21 Camera resolution was 1360 pixels × 1024 pixels, and DMAS accuracy for marker centroid tracking was rated at ± 0.005 mm. Construct gapping was defined as the difference in displacement between the markers at the tissue–suture interface and the markers on the bone. Tissue deformation was then defined as the displacement between the markers at the tissue–suture interface and the markers on the muscle belly. Mean gapping was defined from anterior to posterior across the construct using 3 sets of fiducial markers.

A 0.1-MPa pre-stress (applied force/tendon cross-sectional area) was applied to each construct to determine the starting position for the deformation profile. Each repair underwent 1000 cycles of uniaxial load-controlled displacement between 0.1 and 1.0 MPa of effective stress at 1 Hz. Effective stress was determined as the ratio of applied force to cross-sectional area of the tendon at harvest to normalize the applied loads between tendons of varying size. During cyclic testing, gapping of more than 5 mm was defined as construct failure.22 After cyclic loading, each construct was loaded to failure at 1.0 mm/s. Ultimate failure load was defined as the highest load achieved at the maximum displacement before rapid decline in load supported by the construct.