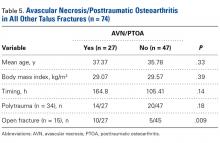

Analysis of AVN/PTOA in All Other Talus Fractures (Table 5)

Of the 74 patients with talus fractures without dislocations, 27 (36.5%) developed AVN/PTOA during the follow-up period, and 47 (63.5%) did not. There was no significant difference in mean age (37.37 years for AVN/PTOA, 35.78 years for no AVN/PTOA; P = .33), BMI (29.07 kg/m2 for AVN/PTOA, 29.57 kg/m2 for no AVN/PTOA; P = .39), or surgical timing (164.8 hours for AVN/PTOA, 105.41 for no AVN/PTOA; P = .14). Direct comparison of the proportions of polytrauma to development of AVN/PTOA in patients with talus fractures without dislocations revealed no significant difference. Fourteen of the 27 patients who developed AVN/PTOA had polytrauma, and 23 of the 47 who did not develop AVN/PTOA had polytrauma (P = .18). Direct comparison of the proportions of open injuries to development of AVN/PTOA in patients with talus fractures without dislocations revealed a significant difference (P = .009). There was a significant difference in follow-up time between these groups. Patients who had talus fractures without dislocations and developed AVN/PTOA were followed for a mean of 154.3 weeks, and those who did not develop AVN/PTOA were followed for a mean of 216 weeks (P = .02).Discussion

Our results showed that time from talus fracture-dislocation to surgical reduction had no effect on development of AVN/PTOA. The findings in this largest series to date agree with earlier findings1,8,15,16,24 and add to the volume of literature suggesting that time to surgical reduction of talus fractures and talus fracture-dislocations does not markedly affect outcome.

Talus fractures continue to present a significant treatment dilemma. Despite recent improvements in surgical techniques and overall management of these injuries, rates of AVN and PTOA have not significantly decreased.1,16,23 At most treating facilities, talus fracture-dislocations are considered surgical emergencies/urgencies, and every effort is made to reduce and surgically address these injuries as soon as possible.1,13

In this study, rates of AVN/PTOA were 41% (all talus fractures) and 50% (displaced talar neck fractures), and the difference was not significant (Table 3). These rates are higher but consistent with previously reported rates (range, 14%-49%).1,2,7-9,12,14,24 There was no difference in surgical timing for development of AVN/PTOA. We analyzed the cases of all patients who had talus fractures and developed AVN/PTOA (43/106). Within this group, there were no significant differences in surgical timing, age, sex, polytrauma, or BMI between patients who developed AVN/PTOA and those who did not. Compared with patients who did not develop AVN/PTOA, those who developed AVN/PTOA were significantly more likely to have open injuries. This finding, consistent with those in other reports9,12,13 (Table 3), indicates outcome is more likely related to injury severity and not necessarily injury class.

We retrospectively analyzed talus fractures and talus fracture-dislocations to determine if urgent surgical management affects outcomes. Current practice at our institution is to routinely reduce and surgically address these fractures urgently, often during the middle of the night, when orthopedic resources are reduced. Our study found a significant difference in surgical timing for patients with talus fracture-dislocations and patients with talus fractures without dislocations (Table 2). Given our findings, urgent surgical reduction and fixation are not indicated to preserve the talus blood supply and prevent AVN/PTOA, though we still recommend urgent surgical management in the setting of an open wound, skin necrosis, or soft-tissue/neurovascular compromise.

This study had several limitations, primarily related to its retrospective nature. Surgical timing was defined as time from injury, as noted in the medical record, to operating room start. In some instances, time of injury was not noted in the medical record, and time of presentation to emergency room was used instead. Thus, surgical timing for these patients may have been longer than identified. In addition, given the rare injury pattern and the retrospective design, this study was susceptible to type II error and may have been underpowered to detect whether time to surgical reduction predicted complications. Also, the study did not address functional outcome as measured by validated outcome scores. Outcome measures were obtained in many but not all cases, making functional outcome measurement difficult. Similarly, the quality of the anatomical reductions was not assessed, potentially affecting complication rates. Postoperative reduction assessment, possibly performed with computed tomography, is an avenue of further study.