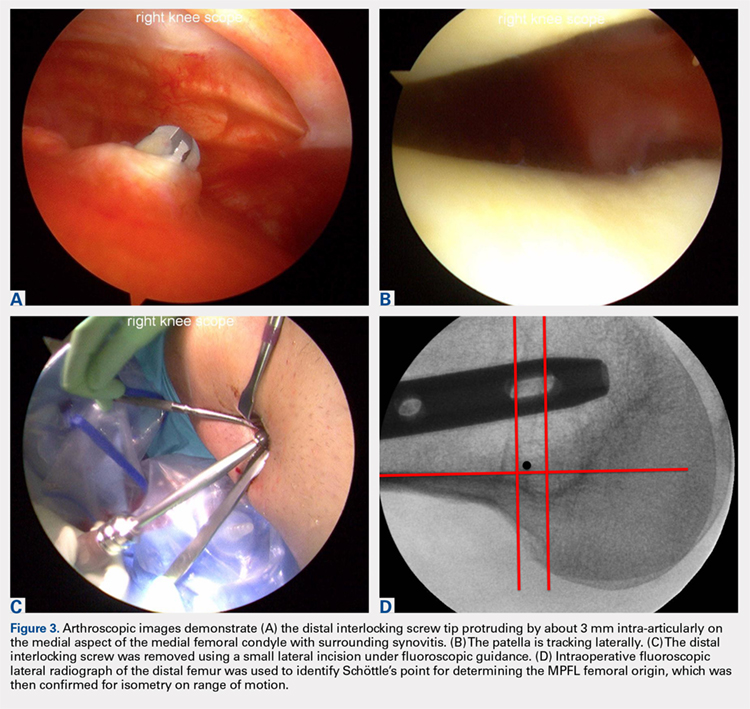

The patient elected to have a right knee arthroscopic-assisted MPFL reconstruction and removal of the distal interlocking screw. Diagnostic arthroscopy revealed the distal interlocking screw to be intra-articular medially, prominent by 3 mm causing attritional disruption of the mid-substance MPFL (Figure 3A). The patella was noted to be subluxated and tracking laterally (Figure 3B). Both the anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament were intact, and menisci and articular cartilage were normal. The distal interlocking screw was removed under fluoroscopic guidance through a small lateral incision (Figure 3C).

Due to the nature of the longstanding attritional disruption of the MPFL in this case with associated patellar instability over a 2-year period, the decision was made to proceed with formal MPFL reconstruction as opposed to repair. A 2-cm incision was made at the medial aspect of the patella. The proximal half of the patella was decorticated. Guide pins were placed within the proximal half of the patella, ensuring at least a 1-cm bone bridge between them, and two 4.75-mm SwiveLock suture anchors (Arthrex) were inserted. A semitendinosus graft was used for MPFL reconstruction with the 2 ends of the graft secured to 2 suture anchors with a whipstitch. Lateral fluoroscopy was used to identify Schöttle’s point, denoting the femoral origin of the MPFL9 (Figure 3D). A 2-cm incision was made at this location. A guide pin was then placed at Schöttle’s point under fluoroscopic guidance, aimed proximally, and the knee was brought through a range of motion (ROM), to verify graft isometry. Once verified, the guide pin was over-reamed to 8 mm. The layer between the retinaculum and the capsule was carefully dissected, and the graft was passed extra-articularly in the plane between the retinaculum and the capsule, out through the medial incision, and docked into the bone tunnel. An 8-mm BioComposite interference screw (Arthrex) was then placed with the knee flexed to 30°. The knee was then passed through a ROM and an arthroscopic evaluation confirmed that the patella was no longer subluxated laterally. There was normal tracking of the patellofemoral joint on arthroscopic evaluation.

Postoperatively, the patient was maintained in a hinged knee brace for 6 weeks. He was weight-bearing as tolerated when locked in full extension beginning immediately postoperatively, and allowed to unlock the brace to start non-weight-bearing active flexion and extension with therapy on postoperative day 1. Radiographs confirmed removal of the distal interlocking screw (Figures 4A, 4B). Following surgery, the patient experienced resolution of his effusions, no recurrent patellar instability at 1-year postoperative, and was able to return to his ADL and recreational sporting activities (Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS] ADL, 100; KOOS sporting and recreational activities, 95; quality of life, 100; Marx Activity Rating Scale, 12).

DISCUSSION

The MPFL connects the superomedial edge of the patella to the medial femur and is injured in nearly 100% of patellar dislocations.6 The femoral origin lies between the adductor tubercle and the medial epicondyle.7 The MPFL prevents lateral subluxation of the patella and acts as the major restraint during the first 20° of knee flexion. Although radiographic parameters for identifying the MPFL femoral origin have been defined by both Schöttle and colleagues9 and Stephen and colleagues10, it is important to check the isometry intraoperatively through a ROM when performing MPFL reconstruction. In this case, the patient’s history and physical examination showed patellar instability, which was determined to be iatrogenically related to the distal interlocking screw rupture of the MPFL. Following screw removal and MPFL reconstruction, the patient had no further symptoms of pain, effusion, or patellar instability and returned to his normal activities.

Femoral malrotation following intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures is a common complication,4 with a 22% incidence of malrotation of at least 15° in 1 series from an academic trauma center.11 There are mixed data as to whether malrotation is more common in complex fracture patterns, in cases performed during night hours, and in cases performed by non-trauma fellowship-trained surgeons.11-13 The natural history of malrotation is not well elucidated, but there is some suggestion that it alters load bearing in the distal joints of the involved leg including the patellofemoral joint. Patients also may not tolerate malrotation due to the abnormal foot progression angle, particularly with malrotation >15°.4 In this case, the patient’s initial femoral nail was placed in an externally rotated position, requiring revision. The result of this was an unusual trajectory of the distal interlocking screw from posterolateral to anteromedial. Combined with the prominent screw tip, the trajectory of this distal interlocking screw likely contributed to the injury to the MPFL observed in this case. This trajectory would also pose potential risk to the common peroneal nerve, which is usually situated posterior to the insertion point for distal femoral interlocking screws. The prominent distal interlock screw is a well-recognized problem with femoral intramedullary nails. This issue results from the tapering of the width of the distal femur from being larger posteriorly to being smaller anteriorly. To avoid placement of a prominent distal interlocking screw, surgeons often will obtain an intraoperative anterior-posterior radiograph with the lower extremity in 30° of internal rotation to account for the angle of the medial aspect of the distal femur.

This practice represents, to our knowledge, a previously unreported cause of patellar instability as well as an unreported complication of antegrade femoral intramedullary nailing. Surgeons treating these conditions should consider this potential complication and pursue advanced imaging if patients present with these complaints after femoral intramedullary nail placement. Knowledge of both MPFL origin and insertional anatomy and avoidance of prominent distal interlocking screws in the region of the MPFL, if possible, would likely prevent this complication.

Limitations of this study include the case report design, which makes it impossible to comment on the incidence of this complication or to make comparisons regarding treatment options. There is, of course, the possibility that the patient had a concurrent MPFL injury from the injury in which he sustained the femur fracture. Nevertheless, the clinical history, examination, imaging, and arthroscopic findings all strongly suggest that the prominent distal interlocking screw was the cause of his MPFL injury and patellar instability. Finally, the point widely defined by Schöttle and colleagues12 was used for MPFL reconstruction in this case based on an intraoperative true lateral radiograph of the distal femur. It should be noted that recent literature has debated the accuracy of this method for determining the femoral origin, the anatomy of the MPFL in relation to the quadriceps, and type of fixation for MPFL reconstruction with some advocating soft tissue only fixation.14-17 For purposes of this case report, we focused on a different cause of MPFL disruption in this patient and our technique for MPFL reconstruction.

CONCLUSION

This case demonstrates that iatrogenic MPFL injury is a potential complication of antegrade femoral nailing and a previously unrecognized cause of patellar instability. Surgeons should be aware of this potential complication and strive to avoid the MPFL origin when placing their distal interlocking screw.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.