RESULTS

A total of 29 patients (24 males, 5 females) with 32 ASR hip replacements were included in this study. Indications for surgery comprised osteoarthritis (28 hips, 87.5%) and avascular necrosis of the hip (4 hips, 12.5%). Mean age and BMI were 55.2 years and 28.9 kg/m2, respectively. A total of 2 patients (6.9%) died of an unrelated cause (1 myocardial infarct, 1 suicide), and 1 patient was lost to follow-up (3.4%), leaving 26 patients with 28 hip replacements, all of whom finished a 5-year minimum follow-up.

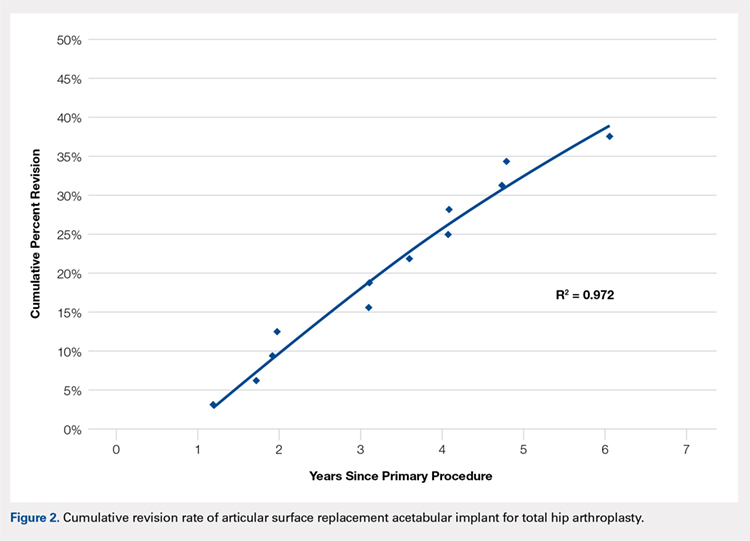

No implant failures were noted in the first year. The 5-year revision rate reached 34.4% (10 patients with 11 hip replacements). Mean time to revision for this subgroup was 3.1 years. Overall, an implant failure was observed in 37.5% of patients (11 patients with 12 hip replacements) at a mean postoperative follow-up of 6.2 years (Figure 2). Indications for implant revision were pain in 11 (92.7%) cases and infection in 1 (8.3%).

Of the 11 hips revised due to pain, 9 were performed by the original surgeon (8 were completed with primary acetabular components, 1 with a revision shell). Figure 3 shows a bilateral revision performed with primary acetabular components and retained DePuy Synthes Pinnacle femoral stems. In all these cases except 1, the ASR component was grossly loose. One case presented with pseudotumor and impingement between the femoral prosthetic neck and acetabular component after migration of a loose component. After revision, the patient returned with substantial anterior hip pain and heterotopic ossification, and failed conservative treatment, requiring another surgery with prosthesis retention, removal of heterotopic ossification, and iliopsoas lengthening. The surgery successfully relieved the symptoms. No other patients required additional surgery after their revision. In comparison to the original ASR component, the revision shell was 2 to 4 mm larger in diameter. No patient required component revision at a mean of 2.9 years after the revision surgery.

The patient with secondary revision developed a hematogenous streptococcal infection after a dental procedure performed without prophylactic antibiotics. The patient was initially lost to follow-up after the primary surgery and reported no antecedent pain prior to the revision. A substantial metal fluid collection was identified in the hip at the time of débridement and without component loosening. After débridement, the patient developed persistent metal stained wound drainage, necessitating ultimate successful treatment with a 2-stage exchange procedure.

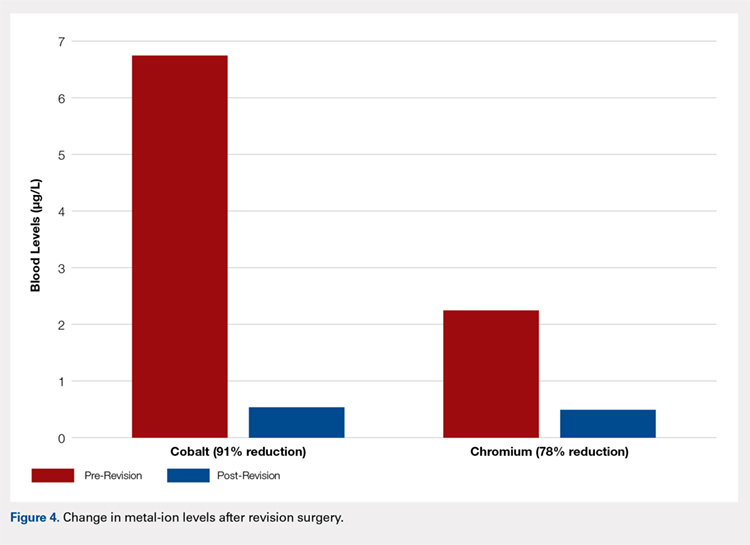

Age (P = .76), gender (P = .49), BMI (P = .29), acetabular component abduction angle (P = .12), and acetabulum size (P = .59) were not associated with an increased rate for hip failure (Table). Blood cobalt (7.6 vs 6.8 µg/L, P = .58) and chromium (5.0 vs 2.2 µg/L, P = .31) levels were not significantly higher in the revised group when compared with those of the unrevised group. The upper limits of blood cobalt and chromium levels reached 18.9 and 15.9 µg/L for the revised group and 16.8 and 5.4 µg/L for the non-revised group, respectively. In the revised group, a 91% decrease in cobalt and 78% decrease in chromium levels were observed at a mean of 6 months after the revision (Figure 4).

Table. Variables Not Associated with Early ASR Failure

No Failure (n = 20) | Failure (n = 12) | P value | ||

Age (years) | 55.4 ± 6.4 | 54.7 ± 6.3 | .76 | |

BMI (kg/m2) | 29.7 ± 6.7 | 27.4 ± 4.0 | .29 | |

Gender | .49 | |||

Female | 3 (15%) | 3 (25%) | ||

Male | 17 (85%) | 9 (75%) | ||

Acetabulum size (mm) | 59.1 ± 3.9 | 58.3 ± 3.8 | .59 | |

Abduction angle (degrees) | 44.9 ± 4.5 | 42.3 ± 3.8 | .12 | |

Serum levels (µg/L) | ||||

Cobalt | 6.8 ± 6.0 | 7.6 ± 4.7 | .58 | |

Chromium | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 5.0 ± 5.0 | .31 | |

Continue to: Discussion...