AMSTERDAM – Results of a new Danish national study suggest the effects of prophylactic beta-blocker therapy in patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery are considerably more heterogeneous than portrayed in current pro-prophylaxis practice guidelines or, at the opposite extreme, in a recent highly critical meta-analysis.

"This is an extraordinarily confusing area at the moment," Dr. Charlotte Andersson observed in presenting the Danish national registry findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

She reported on 28,263 adults with ischemic heart disease who underwent noncardiac surgery during 2004-2009. Hip or knee replacements were the most common operations, accounting for roughly one-third of the total. Patients were followed for 30 days postoperatively for the composite endpoint of acute myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or cardiovascular death, as well as for 30-day all-cause mortality.

In short, the effects of prophylactic beta-blocker therapy depended upon the type of background ischemic heart disease a surgical patient had.

"Our data suggest a beneficial effect of beta-blockers among patients with heart failure, perhaps a beneficial effect as well among patients with an MI within the previous 2 years, but no beneficial effect among patients with a more distant MI, and perhaps even harm associated with beta-blocker therapy among patients with neither heart failure nor a history of MI," according to Dr. Andersson of the University of Copenhagen.

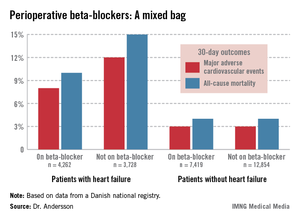

The study population included 7,990 patients with heart failure, 53% of whom were on beta-blockers when they underwent noncardiac surgery. Those on beta-blockers fared significantly better in terms of the study endpoints (see graphic).

In contrast, 30-day outcomes in the 37% of patients without heart failure were identical regardless of whether or not they were on beta-blockers at surgery.

In a multivariate analysis, the use of beta-blockers in noncardiac surgery patients with heart failure was associated with a 22% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and an 18% reduction in all-cause mortality compared with no use of beta-blockers, both of which were statistically significant advantages. The analysis was adjusted for patient demographics, acute versus elective surgery, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, cancer, anemia, smoking, alcohol consumption, cerebrovascular disease, and American Society of Anesthesiologists score.

Among the 1,664 patients with an MI within the past 2 years, being on a beta-blocker at the time of surgery was associated with an adjusted highly significant 46% reduction in MACE and a 20% decrease in all-cause mortality, compared with no use of beta-blockers.

For the 1,679 patients with an MI 2-5 years prior to surgery, being on a beta-blocker was associated with a 29% reduction in the risk of MACE and a 26% reduction in 30-day all-cause mortality.

Among the 5,018 patients with an MI more than 5 years earlier, the use of beta-blockers at surgery was associated with a 35% greater risk of MACE than in nonusers of beta-blockers as well as a 33% increase in all-cause mortality. These differences in adverse outcomes rates barely missed achieving statistical significance.

Perhaps the most striking study finding was that patients with no prior MI or heart failure who were on a beta-blocker at the time of noncardiac surgery had a 44% increased risk of 30-day MACE and a 30% higher all-cause mortality, compared with those not on a beta-blocker, with both differences being significant.

Session cochair Dr. Elmir Omerovic thanked Dr. Andersson for a presentation that "really adds important new information" and asked whether she had been surprised by the findings.

"Yes, I have to say I was surprised by the increased risk in patients without prior MI or heart failure, because the ESC [European Society of Cardiology] guidelines state as a class I recommendation that all patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery should be on a beta-blocker. Perhaps we should reevaluate beta-blockers in noncardiac surgery," Dr. Andersson replied.

Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines also endorse perioperative beta-blockade in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing vascular or intermediate-risk noncardiac surgery.

She noted that in drawing up the current guidelines, the ESC and ACC/AHA committees relied heavily on strongly positive randomized clinical trials whose validity has recently been called into question in a major research scandal. Indeed, the lead investigator in those studies, Dr. Don Poldermans – who also happened to be chairperson of the ESC guidelines-writing task force – has been dismissed from the faculty at Erasmus University in Rotterdam.

Dr. Omerovic, of Sahlgrenska University, Gothenburg, Sweden, asked for Dr. Andersson’s thoughts regarding a new meta-analysis by investigators at Imperial College London which excluded the suspect Dutch clinical trials. The investigators concluded that initiation of perioperative beta-blocker therapy was associated with a 27% increase in 30-day all-cause mortality, a 27% reduction in nonfatal MI, a 73% increase in stroke, and a 51% increase in hypotension.