CHICAGO – When Superstorm Sandy was done barreling across New York City and the surrounding coast 14 months ago, flooding streets and knocking out power to millions, Dr. Laura Evans, director of the medical intensive care unit at Bellevue Hospital along the East River in Manhattan, emerged weary and wiser.

At one point, the ICU faced the real possibility of having just a handful of working power outlets to serve dozens of patients, and the number of crucial decisions to be made rose along with the water level. "Prior to the storm, disaster preparedness was not a core interest of mine, and it’s something I hope never to repeat," Dr. Evans told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

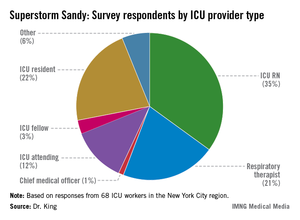

In a recent survey, ICU practitioners who endured havoc caused by Sandy in the New York City region reported having had little to no training in emergency evacuation care. "When I look at these data, I think there is a mismatch in terms of our self-perception of readiness compared to what patients actually require in an evacuation. It’s in stark contrast to the checklist we use every single day to put in a central venous catheter," said Dr. Mary Alice King, who presented her research as a copanelist with Dr. Evans. Dr. King is medical director of the pediatric trauma ICU at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Contingency for loss of power

The nation’s oldest public hospital, Bellevue is adjacent to New York’s tidal East River. The river’s high tide the evening of Oct. 29, 2012, coincided with the arrival of the storm’s surge, and within minutes the hospital’s basement was inundated with 10 million gallons of seawater. And then the main power went out, taking with it the use of 32 elevators, the entire voice-over-Internet-protocol phone system, and the electronic medical records system, Dr. Evans said. The flood also knocked out the hospital’s ability to connect to its Internet servers. "We had very impaired means of communication," Dr. Evans said.

Survey data presented by Dr. King underscored that loss of power affects ICU functions in virtually all ways. The number one tool Dr. King’s survey respondents said they’d depended on most during their disaster response was their flashlights (24%); meanwhile, the top two items the respondents said they wished they’d had on hand were reliable phones, since, as at Bellevue, many of their phones were powered by voice-over-Internet protocols which, for most, went down with power outages; and backup electricity sources such as generators.

Leadership plan

Of the 68 survey respondents, 34% of whom were in evacuation leadership roles, Dr. King said only 23% admitted to having felt ill prepared to manage the pressure and details necessary to safely evacuate their patients. "As nonemergency department hospital providers, we receive little to no training on how to evacuate patients," said Dr. King.

In Bellevue’s case, Dr. Evans said that there was a leadership contingency already in place because of the hospital’s having been prepared the year before, when Hurricane Irene muscled its way up the Northeast’s Atlantic coast, also causing flooding and wind damage, though on a far smaller scare. "We had an ad hoc committee," said Dr. Evans. "Although we didn’t know exactly who would be on it because we didn’t know who would be there during the storm, we knew we would have medical, nursing, and ethical leaders to make resource allocation decisions." Most important about the leadership committee’s makeup, she said, was that ultimately, "none of us were directly involved in patient care, so none of us had the responsibility for being advocates. We wanted the attending physicians to be able to advocate for their patients."

The committee discerned that if backup generators failed, the ICU would have only six power outlets to depend on for its almost 60 patients. "The question was, whom would they be allocated for out of the 56 patients?

"Our responsibility was to make the wisest decisions about allocating a scarce resource," Dr. Evans said.

Practice the plan

Dry runs matter. "Forty-seven percent of survey respondents said that patient triage criteria were determined at the time of [the storm]," and a third of those surveyed said they weren’t aware of any triage criteria, Dr. King said.

And once plans are made, "it’s important to drill them," emphasized Dr. King’s copresenter Dr. Colin Grissom, associate medical director of the shock trauma ICU at Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, Utah. Superstorm Sandy, for all its havoc, came with some notice – the weather forecast. However, he pointed out that typically disasters happen without warning: "More than half of all hospital evacuations occur as a result of an internal event such as a fire or an intruder."