Categorical variables were statistically analyzed with χ2 tests, and continuous variables were analyzed with Student t test, analysis of variance, and univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Intrarater reliability was measured with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). All statistical analysis was performed with Predictive Analytics SoftWare Statistics Version 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

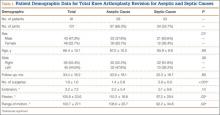

Ninety-one consecutive patients (43 men, 48 women) were included in this study. Mean (SD) age was 66.4 (10.1) years. Mean (SD) preoperative ISR in septic and aseptic cases was 0.94 (0.25) for men and 1.02 (0.23) for women (P = .10). Mean postoperative ISR in septic and aseptic cases was 0.84 (0.27) for men and 0.99 (0.23) for women (P = .004). There was a sex difference between septic and aseptic revisions. There were 22 men and 36 women in the aseptic group and 21 men and 12 women in the septic group (P = .01). Men were more likely than women to have septic revisions and patella baja. Table 1 compares the patient demographics of the 2 patient populations. Mean (SD) number of surgeries, including irrigation and débridement procedures before reimplantation, was larger for septic revisions, 2.9 (0.9), than for aseptic revisions, 1.4 (0.8) (P < .001).

Infection was the most common reason for revision and accounted for 33.7% (34/101) of all revisions. Noninfectious indications, in declining order of frequency, included loosening (23.8%, 24/101), instability (11.9%, 12/101), pain (11.9%, 12/101), osteolysis (5.0%, 5/101), polyethylene wear (5.0%, 5/101), failed unicompartmental knee (4.0%, 4/101), stiffness (3.0%, 3/101), and patellar problems (2.0%, 2/101) (Table 2). ISR decreased significantly only in infected revisions. It is important to note that there was not a high incidence of stiffness or patellofemoral failure in revision patients before surgery.

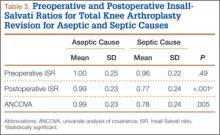

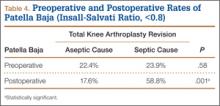

Mean (SD) ISR did not differ between groups before surgery, 1.00 (0.25) for aseptic and 0.96 (0.22) for septic (P = .49), but differed significantly after surgery, 0.99 (0.23) for aseptic and 0.77 (0.24) for septic (P < .001) (Figure 2). The univariate ANCOVA also demonstrated a postoperative difference between groups when taking the preoperative ratio into account: 0.99 (0.23) for aseptic and 0.78 (0.24) for septic (P = .005) (Table 3). Before surgery, 22.4% and 23.9% of the aseptic and septic groups, respectively, had patella baja (P = .58). After surgery, 17.6% and 58.8% of the aseptic and septic groups had patella baja (P = .001) (Table 4). The ICC for preoperative ISR was 0.94, and the ICC for postoperative ISR was 0.96, which indicates excellent agreement of measurements between the 2 blinded investigators.

ROM differed between septic and aseptic groups owing to the difference in postoperative flexion. Mean (SD) postoperative extension was 2.2° (5.4°) for the aseptic group and 5.1° (9.8°) for the septic group—not significantly different (P = .13). Mean (SD) postoperative flexion was 110.2° (18.8°) for the aseptic group and 97.2° (29.4°) for the septic group—significantly different (P = .02). The groups differed significantly (P = .02) in mean (SD) ROM: 108.0° (20.7°) for aseptic and 92.2° (34.6°) for septic (Table 1). ROM was also significantly associated with patella baja (P = .04), as patients with ISR of less than 0.8 had mean (SD) postoperative ROM of 95.1° (31.6°), and patients without patella baja had mean (SD) postoperative ROM of 106.8° (23.6°).

For the septic group, mean (SD) time between first and second stages was 13.0 (8.3) weeks (range, 1-44.3 weeks). Mean (SD) timing of spacer placement was not statistically significantly different (P = .90) between patients who had patella baja, 12.9 (8.8) weeks, and patients who did not have patella baja, 13.2 (7.8) weeks.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that TKAs done for septic reasons resulted in a higher incidence of patella baja and decreased ROM. Incidence of patella baja was higher both before and after revision in septic TKAs than in aseptic TKAs, proving the hypothesis under study. Prerevision incidence was not significantly different, but there was a trend that could not be ignored. This may suggest that there is already an ongoing process in the infected knee that contributes to patella baja; the precise etiology remains unclear and is likely multifactorial. For example, scar formation may be increased in patients with chronic infection, predisposing to patella baja. This assertion is indirectly supported by a recent study from our institution revealing longer average surgical time in septic versus aseptic knee revisions; the difference was thought to reflect increased scar-tissue formation.16 That study also found that patients who underwent septic revisions had significantly more surgical procedures than patients who underwent aseptic revisions. Repetitive surgeries—specifically, repetitive arthrotomies during irrigation and débridement before reimplantation—lead to increased scar formation, which may contribute to preoperative and postoperative patella baja. This may be reflected in the findings that ROM was decreased in patients in the septic group versus patients in the aseptic group and that ROM was decreased in patients with patella baja. In addition, our study found that male patients were more likely to undergo TKA revision for septic reasons and to develop postoperative patella baja. This finding contrasts with that of a study5 that compared preoperative and postoperative ISR in primary TKA and found that women were more likely than men to have patella baja. Although women are more likely to undergo TKA revision,17 men may be more susceptible to infection and subsequent patella baja.