Fat embolism syndrome (FES) was first described by Von Bergmann in 1873 in a patient with a fractured femur.1 While fat within the circulation (fat embolism) is relatively common following long-bone fracture, the clinical pattern of symptoms that make up FES is less so, occurring in 1% to 3% of isolated long-bone fractures and 5% to 10% of patients with multiple skeletal trauma.1 A variety of clinical, laboratory, and imaging criteria has been described, classically by Gurd in 1970 (Table).1-6 Most commonly, however, it is a diagnosis of exclusion when the classic triad of respiratory difficulty, neurologic abnormalities, and a characteristic petechial rash are present in the appropriate clinical setting.6

The neurologic sequelae of this syndrome can range from headache, confusion, and agitation to stupor, focal neurologic signs, and, less commonly, coma.7 Onset of these symptoms usually occurs between 24 hours and 48 hours (mean, 40 hours) after trauma.1 While these neurologic manifestations occur in up to 86% of patients with FES, it is rare for them to be present without the pulmonary symptoms of dyspnea, hypoxemia, and tachypnea, which are the most common presenting symptoms of the disease.1-6 In this case report, we describe severe, rapid-onset neurologic manifestations, without the typical pulmonary involvement, as the primary clinical presentation of FES in a polytrauma patient. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A previously healthy 50-year-old man presented to the emergency room in transfer from an outside hospital after a rollover motor vehicle collision in which he was ejected approximately 50 feet. Injuries included a right proximal humerus fracture/dislocation (Figure 1), right ulnar styloid fracture, L1 compression fracture, and multiple rib fractures. On admission, the patient had an ethanol level of 969 mg/L (.097%) and a urine drug screen positive only for opioids, presumably because of pain medication given that day. He denied a history of alcohol abuse and reported consuming 2 to 3 beers per week. The patient was awake, alert, and oriented with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 15. He was tachycardic (heart rate, 126), tachypneic (respiratory rate, 24), and febrile (temperature, 38.6°C [101.5°F]), and his white blood cell count was elevated at 29.5×109/L. On examination, his right arm was found to be neurovascularly intact; it was placed in a sling with a forearm splint, and the patient was admitted to the intermediate special care unit on spine precautions with a plan for right shoulder hemiarthroplasty the following day.

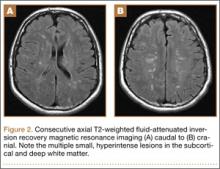

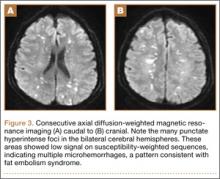

Overnight the patient’s mental status began to deteriorate, and approximately 10 hours after initial assessment, he was not answering questions but was able to respond to some commands. On hospital day 2, approximately 20 hours after initial assessment, the patient had a GCS of 8, was not responding to commands, and moved only in response to painful stimuli. The patient had been prescribed morphine by patient-controlled analgesia and had received intravenous hydromorphone on the day of admission, although the amount of medication delivered was not thought adequate to explain this deterioration. On the morning of hospital day 2, noncontrast brain computed tomography (CT) was normal with no evidence of intracranial hemorrhage or infarct. This was followed by brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with the T2-weighted images showing numerous, small hyperintense lesions in subcortical and periventricular white matter, corpus callosum, basal ganglia, brain stem, and cerebellar hemispheres (Figure 2). The lesions also showed hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted MRI and were interpreted to be consistent with multiple, tiny infarcts (Figure 3). In addition, susceptibility-weighted sequences showed low signal in the same areas, suggesting multiple microhemorrhages, a pattern consistent with FES. Oxygen saturations remained 95% to 99%, and chest radiograph revealed clear lung fields without infiltrate. On hospital day 2, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and intubated for airway protection owing to an inability to clear secretions, although arterial blood gas levels remained normal. An echocardiogram revealed no right-to-left shunt, such as a patent foramen ovale (PFO); an electroencephalogram showed no seizure-like activity. No petechial rash was noted on skin examination. The patient was treated with supportive care. Right shoulder hemiarthroplasty was performed on hospital day 7 without complications (Figure 1). On hospital day 13, the patient was following commands and on day 14 he was extubated. His mental status continued to improve, and he was discharged to a rehabilitation facility after 36 days. On last follow-up, 6 months after initial injury, the patient was recovering well with no residual neurologic deficits and only minor limitation in range of motion of the right shoulder.