Discussion

Successful ACL reconstruction depends heavily on anatomical tunnel positioning. Failure to place the femoral tunnel in the anatomical footprint of the native ACL results in incomplete restoration of knee kinematics, rotational instability, and graft failure.1-7 Two common techniques for creating this tunnel, transtibial and anteromedial drilling, can reliably place it in an anatomical position. Each technique, however, has limitations. Transtibial drilling can place the tunnel too vertical and high in the notch, or produce a short tibial tunnel close to the joint line.8-10 Anteromedial drilling requires knee hyperflexion, risks damaging the articular cartilage and nearby neurovascular structures, and makes visualization difficult.13-16

One option for addressing some of the difficulties and limitations with anteromedial drilling is to use flexible guide pins and reamers, as first introduced by Cain and Clancy.1 In a cadaveric study, Silver and colleagues17 demonstrated that interosseous tunnels drilled with flexible guide pins were on average more than 6 mm longer than those drilled with rigid pins and consistently were 40 mm or longer. In addition, all tunnels drilled with flexible guide pins were on average 42.3 mm away from the peroneal nerve and 26.1 mm away from the femoral origin of the lateral collateral ligament—safe distances.

Steiner and Smart18 compared flexible and rigid instruments used to drill transtibial and anteromedial (without hyperflexion) anatomical femoral tunnels in ACL reconstruction in cadaveric knees. Although transtibial drilling with flexible pins produced anatomical tunnels, the tunnels were shorter, and the pins exited more posterior in comparison with anteromedial drilling with flexible pins. Transtibial tunnels drilled with rigid pins were nonanatomical and exited more superior and anterior on the femur, resulting in longer tunnels. Anteromedial tunnels drilled with rigid and flexible pins were placed anatomically, but flexible pins produced longer tunnels, did not require hyperflexion (120°), could easily be placed with the knee in 90° of flexion, and did not violate the posterior femoral cortex.

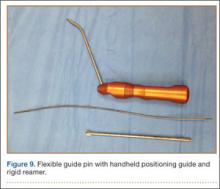

Five times in our early experience with flexible guide pins and reamers, the reamer broke when LFC reaming was initiated. In each case, the broken reamer was retrieved. However, these complications resulted in increased surgical time and cost. In addition, an unretrievable reamer could have caused further injury and suboptimal outcomes. We subsequently developed an anteromedial technique that uses a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer to place the femoral tunnel in an anatomical position (Figure 9). The flexible pin provides consistent placement of anatomical tunnels averaging 35 to 40 mm in length. Use of the flexible pin does not require constant hyperflexion of the knee, and it allows for better visualization of the posterior wall of the LFC, ensures anatomical graft placement, and decreases the risk of damaging articular cartilage and causing neurovascular injury. Use of the rigid reamer negates the risks and additional costs associated with reamer breakage. It is unclear why 5 flexible reamers broke during our early use of flexible guide pins and reamers, but it is possible that, because of the patients’ anatomy, placement of the pin in the correct anatomical position in the ACL footprint put a significant amount of abnormal stress on the reamer during tunnel reaming, leading to breakage and failure.

A short femoral tunnel is a common complication of using an anteromedial portal for tunnel drilling.13-16 With the technique we have been using, tunnel lengths average 35 to 40 mm. To address the occasional shorter tunnel, we use Endobutton Direct (Smith & Nephew), which allows for direct fixation of the graft on the button, maximizing the amount of graft in the femoral tunnel and minimizing graft–tunnel length mismatch. In the event there is a lateral wall breach during overdrilling with the reamer, the femoral graft may be secured with screw and post, with interference screw, or with the larger Xtendobuton (Smith & Nephew).

We have successfully used this technique with bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) and hamstring autografts, as well as allografts. Complications, such as graft–tunnel length mismatch, have been uncommon, but, when using BPTB grafts, passing the bone block into the femoral tunnel can be difficult because of the sharp turn required.

Conclusion

Successful ACL reconstruction depends heavily on placement of the graft within the anatomical insertion of the native ACL. With the development of techniques that use flexible guide pins and reamers, it has become possible to place longer anatomical femoral tunnels without the need for hyperflexion. Use of a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer allows placement of longer anatomical tunnels through an anteromedial portal, reduces time spent with the knee in hyperflexion, provides better viewing, poses less risk of damage to the articular cartilage and neurovascular structures, and at a lower cost with less risk of reamer breakage. In addition, this technique can be used with a variety of graft options, including BPTB grafts, hamstring autografts, and allografts.