Statistical Analysis

We used Minitab 14 (Minitab, State College, Pennsylvania) to perform all statistical analyses, unpaired Student t tests to compare IKDC and Tegner-Lysholm results between allograft and autograft groups, and χ2 tests to compare revision and reoperation rates between groups. Significance was set at P = .05.

Results

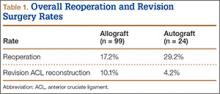

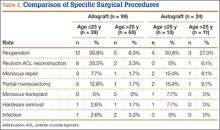

We identified 362 patients who underwent ACL reconstructions at our institution between 2000 and 2008. Of these patients, 302 met the study inclusion criteria. One-hundred twenty-three (40.7%) of the 302 were available for follow-up by telephone interview and/or mailed questionnaire. This follow-up group consisted of 67 males and 56 females. Mean age at surgery was 29 years (range, 17-53 years). Mean follow-up was 50.3 months (range, 11-111 months). Of the 123 patients, 99 underwent allograft ACL reconstruction, and 24 underwent autograft ACL reconstruction. Seventeen (17%) of the 99 allograft cases required additional surgery (Table 1). The reoperation rate for patients under age 25 years (30.8%) was higher than the rate for patients older than 25 years (Table 2). Regarding patients who underwent additional surgeries, mean scores were lower with allograft (Tegner-Lysholm, 59; IKDC, 54) than with autograft (Tegner-Lysholm, 83; IKDC, 79) (Ps = .0025 and .006, respectively).

Revision rates were 10.1% (allograft group) and 4.2% (autograft group) (Table 1). This difference was not statistically significant (P = .18). In the allograft group, the revision rate was higher for patients younger than 25 years (20.5%) than for patients older than 25 years (3.3%) (Table 2). In comparison, in the autograft group, the revision rate was only 4% for patients younger than 25 years. For younger patients, the higher rate of revision with allograft (vs autograft) was statistically significant (P = .038). For older patients, allograft and autograft revision rates did not differ significantly (P = .19). No patient younger than 25 years required revision reconstruction after autograft ACL reconstruction.

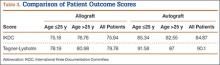

IKDC and Tegner-Lysholm outcome scores for allograft and autograft groups are shown in Table 3. In patients 25 years or younger, IKDC scores were 75.18 after allograft reconstruction and 85.34 after autograft reconstruction—a significant difference (P = .045). In addition, Tegner-Lysholm scores were significantly higher after autograft reconstruction (91.58) than allograft reconstruction (78.19) in these younger patients (P = .003) (Table 3). IKDC and Tegner-Lysholm scores were not significantly different for older patients (Ps = .241 and .211, respectively).

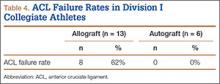

The study also included a subset of 19 primary ACL reconstructions (13 allograft, 6 autograft) performed on Division I athletes from the University of Arizona. (Nineteen [91%] of the 21 athletes in our Division I cohort were available for follow-up.) All these patients were younger than 25 years. All autograft reconstructions were performed with quadruple-stranded gracilis and semitendinosus tendons. ACL graft failure occurred in 8 (62%) of the 13 allograft cases; there were no failures in the autograft group (Table 4). One of the 5 allograft cases that did not fail required multiple surgical débridement procedures for infection, but the graft was ultimately retained. There were no infections among the 6 autograft cases.

Discussion

The ideal graft for ACL reconstruction is still a matter of intense debate. There are many graft options for ACL reconstruction. Both BPTB and hamstring autografts are associated with various graft-specific comorbidities. Anterior knee pain, knee extensor weakness, extension loss, patella fracture, patellofemoral crepitance, and infrapatellar nerve injury have been described with BPTB autografts.13-17 In a meta-analysis of 11 studies comparing BPTB autografts with hamstring autograft, Goldblatt and colleagues17 found more extension loss, kneeling pain, and patellofemoral crepitance in the BPTP group.

Knee flexion weakness, knee flexion loss, increased knee laxity, and saphenous nerve injury have all been described with use of hamstring autografts.16-19 Goldblatt and colleagues17 demonstrated a significant flexion loss in the hamstring group in their meta-analysis as well as increased laxity with both the Lachman test and the pivot shift test. They also found that the hamstring autograft group exhibited side-to-side differences of more than 3 mm on KT-1000 testing when compared with the BPTB autograft group.

Proposed advantages of allograft reconstruction include elimination of donor-site morbidity and/or pain from a less invasive procedure, faster initial recovery, more sizing options, and shorter operative times.4-7 In a 5-year follow-up of patients who had ACL reconstruction with either Achilles allograft or BPTB autograft, Poehling and colleagues7 demonstrated overall similar long-term outcomes between the groups. However, the allograft patients reported less pain 1 and 6 weeks after surgery; better function 1 week, 3 months, and 1 year after surgery; and fewer activity limitations throughout the follow-up period. Lamblin and colleagues20 also found no difference between nonirradiated allograft and autograft tissue in ACL reconstruction in a 2013 meta-analysis of ACL studies published over a 32-year period.