ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

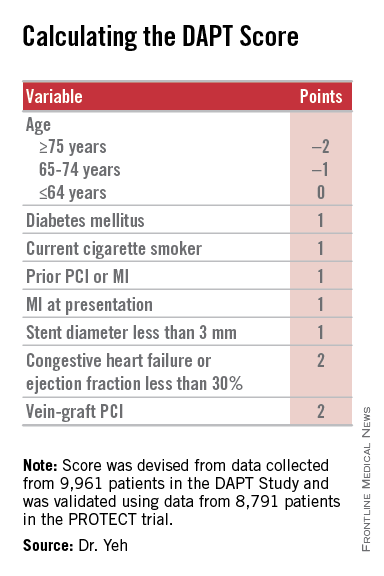

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.