NEW YORK – Mastery is the product of repetition, and it has long been taken for granted that surgeons and centers that perform a high volume of an operation will have better results than those who don’t do the operation as often, but a study out of the United Kingdom has determined just how much better high-volume centers are when it comes to repair of acute type A aortic dissection (ATAD) – and what the in-hospital mortality odds ratio is for lower-volume surgeons.

Specifically, that odds ratio is 1.64 (P = .030), Mohamad Bashir, MD, PhD, MRCS, a research fellow at Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital, said in reporting early results of the study here. Lower-volume surgeons had worse outcomes in 12 of 14 different operative metrics the study evaluated, most notably in-hospital mortality: 20.2% for lower-volume surgeons vs. 15.2% for higher-volume surgeons. “There is an initiative in the U.K. to change the trend,” Dr. Bashir said. Full study results will be published in an upcoming issue of BMJ, he said.

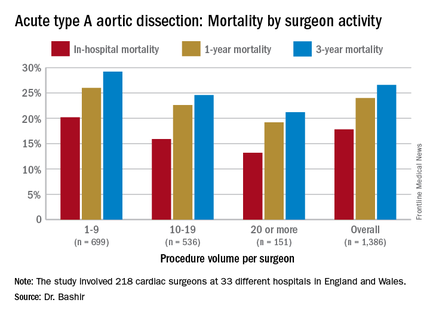

“In-hospital mortality for surgeons who operate on 20 or more procedures is very good at 13.2%, and the same follows for 90-day mortality, one-year mortality and three-year mortality,” Dr. Bashir said.

The study evaluated 1,386 ATAD procedures in the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research database by 218 different cardiac surgeons at 33 different hospitals in England and Wales from April 2007 to March 2013. That would make the average number of procedures per surgeon 6.4, Dr. Bashir said, but a closer look at each surgeon’s case load reveals some disconcerting trends: almost 80% of the surgeons performed fewer than 10 ATAD repairs in the 6-year span of the study, and 34 surgeons, or about 15%, just did a single procedure in that time. The highest-volume surgeon did 32 procedures. The minimum hospital volume was 8 ATAD operations and the maximum was 103.

The study stratified lower- and higher-volume surgeon groups by characteristics of the patients they operated on. “The differences between these two groups are pretty interesting because we noticed that the lower-volume surgeons are actually operating on patients who are diabetic, who are smokers, who use inotropic support prior to anesthesia and who also have an injection fraction that is significant,” Dr. Bashir said.

In drilling down into those characteristics, people with diabetes made up 6% of the lower-volume surgeons’ cases vs. 3.1% of the higher-volume surgeons’ cases, despite an almost 50-50 split in share of procedures between the two surgeon groups. Current smokers comprised 20.5% of the lower-volume surgeons’ patients vs. 15.5% of their high-volume counterparts’ patients. Operative characteristics in terms of urgency of surgery were similar between the two groups. However Dr. Bashir noted, lower-volume surgeons had longer times for cardiopulmonary bypass, aortic cross-clamping, and circulatory arrest.

The study investigators applied a multivariable logistic regression model to determine predictors of in-hospital mortality for ATAD. “The odds ratio (OR) of mortality for lower-volume surgeons is 1.64, which is statistically significant,” Dr. Bashir said. Odds ratios for other predictors are: previous cardiac surgery, 2.51; peripheral vascular disease, 2.15; preoperative cardiogenic shock, 2.05; salvage operation, 5.57; and concomitant coronary artery bypass procedure, 2.98. For 5-year mortality, the odds ratio was 1.37 for the lower-volume surgeons.

Dr. Bashir laid out how the National Health Service can use the study results. “Concentration of expertise and volume to the appropriate surgeons and centers who perform increasingly more work and more complex aortic cases would be required to change the paradigm of acute type A aortic dissection outcomes in the U.K.,” he said. “It is reasonable to suggest that there should be a national standardization mandate and a quality-improvement framework of acute aortic dissection treatment.”

Dr. Bashir had no financial relationships to disclose.