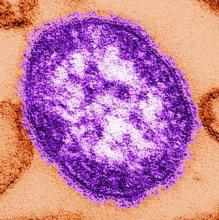

In approximately 42% of recent cases of measles in the United States, the patients were intentionally unvaccinated for nonmedical reasons such as religious or philosophical objections to vaccines, according to a report published online March 15 in JAMA.

Vaccine refusal raised the risk of acquiring measles not only among unvaccinated individuals but also among fully vaccinated people living where the outbreaks occurred, said Dr. Varun K. Phadke of the division of infectious diseases, Emory University, Atlanta, and his associates.

To characterize the contribution of vaccine refusal to recent outbreaks of two vaccine-preventable diseases, the investigators reviewed 18 published studies involving 1,416 measles cases and 32 involving 10,609 pertussis cases. They found that 56.8% of the patients who acquired measles and 24%-45% of those who acquired pertussis were unvaccinated or undervaccinated (hadn’t received all the recommended doses of the vaccines).

In 970 measles cases for which there were detailed data, 405 patients (42%) were intentionally unvaccinated without any medical indications for avoiding the vaccine; these patients avoided immunization against measles because of personal, philosophical, or religious beliefs or cultural norms. Unvaccinated people were up to 35 times more likely than were vaccinated people to acquire the infection. Nonetheless, a higher frequency of vaccine refusal in the geographic area of an outbreak also correlated with a higher measles incidence among the vaccinated people living there.

In eight of the largest pertussis outbreaks for which there were detailed data, 59%-93% of patients were intentionally unvaccinated for nonmedical reasons. Unvaccinated people were up to 20 times more likely than were vaccinated people to acquire the infection. And among people who hadn’t received all recommended the doses of pertussis vaccine, the risk of the infection was proportional to the number of doses they missed. As with measles, a higher frequency of refusal of the pertussis vaccine in the vicinity of a pertussis outbreak correlated with a higher incidence even among the vaccinated people living there. Waning immunity explained only some, not all, of the increased risk among vaccinated individuals, Dr. Phadke and his associates noted (JAMA 2016 March 15;315[11]:1149-58). These findings “have broad implications” for vaccine practice and policy. For example, to restrict peoples’ individual freedom by mandating vaccination, it must first be demonstrated that exemptions harm others living in the community.

To improve vaccine coverage, communities should strengthen state- or school-level enforcement of existing vaccine mandates, as well as increase the difficulty of obtaining a vaccine exemption. They also should “address the reasons for vaccine hesitancy, which may include parental perceptions regarding the risk and severity of vaccine-preventable diseases, the safety and effectiveness of routine immunizations, and confidence in medical professionals, corporations, and the health care system,” the investigators said.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases’ Emory Vaccinology Training Program. Dr. Phadke reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of his associates reported ties to Crucell, Pfizer, Merck, and Parents of Kids with Infectious Diseases.