A 29-year-old woman with a history of frequent migraines presented to her primary care provider for a refill of medication. For the past two years she had been taking rizatriptan 10 mg, but with little relief. She stated that she had continued to experience discrete migraines several days per month, often clustered around menses. The severity of the headaches had negatively affected her work attendance, productivity, and social interactions. She wondered if she should be taking a different kind of medication.

The patient had been diagnosed with migraines at age 12, just prior to menarche. She described her headache as a unilateral, sharp throbbing pain associated with increased sensitivity to light and sound as well as nausea. She denied any history of head trauma. She had no allergies, and the only other medications she was taking at the time were an oral contraceptive (ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate 0.035 mg/0.18 mg with an oral triphasic 21/7 treatment cycle) and fluoxetine 20 mg for depression.

The patient worked daytime hours as a sales representative. She considered herself active, exercised regularly, ate a balanced diet, and slept well. She consumed no more than two to four alcoholic drinks per month and denied the use of herbals, dietary supplements, tobacco, or illegal drugs.

The patient stated that her mother had frequent headaches but had never sought a medical explanation or treatment. She was unaware of any other family history of headaches, and there was no family history of cardiovascular disease. Her sister had been diagnosed with a prolactinoma at age 25. At age 26, the patient had undergone a pituitary protocol MRI of the head with and without contrast, with negative results.

On examination, the patient was alert and oriented with normal vital signs. Her pupils were equal and reactive to light, and no papilledema was evident on fundoscopic examination. The cranial nerves were grossly intact and no other neurologic deficits were appreciated. No carotid bruits were present on cardiovascular exam.

Based on the patient’s history and physical exam, she met the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II)1 diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura (1.1). When asked to recall the onset and frequency of attacks she had had in the previous four weeks, she noted that they regularly occurred during her menstrual cycle.

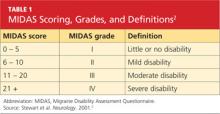

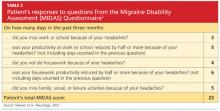

She was subsequently asked to begin a diary to record her headache characteristics, severity, and duration, with days of menstruation noted. The Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire2 (see Tables 1 and 22) was performed to measure the migraine attacks’ impact on the patient’s life; her score indicated that the headaches were causing her severe disability.

The patient’s abortive migraine medication was changed from rizatriptan 10 mg to the combination sumatriptan/naproxen sodium 85 mg/500 mg. She was instructed to take the initial dose as soon as she noticed signs of an impending migraine and to repeat the dose in two hours if symptoms persisted. The possibility of starting a preventive medication was discussed, but the patient wanted to evaluate her response to the combination triptan/NSAID before considering migraine prophylaxis.

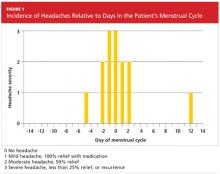

Three months later, the patient returned for follow-up, including a review of her headache diary. She stated that the frequency and intensity of attacks had not decreased; acute treatment with sumatriptan/naproxen sodium made her headaches more bearable but did not ameliorate symptoms. The patient had recorded a detailed account of each migraine which, based on the ICHD-II criteria,1 demonstrated a pattern of headache occurrences consistent with menstrually related migraine. She reported a total of 18 headaches in the previous three months, 12 of which had occurred within the five-day perimenstrual period (see Figure 1).

Based on this information and the fact that the patient’s headaches were resistant to previous treatments, it was decided to alter the approach to her migraine management once more. In an effort to limit estrogen fluctuations during her menstrual cycle, her oral contraceptive was changed from ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate to a 12-week placebo-free monophasic regimen of ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel 20 mg/90 mcg. For intermittent prophylaxis, she was instructed to take frovatriptan 2.5 mg twice daily, beginning two days prior to the start of menses and continuing through the last day of her cycle. For acute treatment of breakthrough migraines, she was prescribed sumatriptan 20-mg nasal spray to take at the first sign of migraine symptoms and instructed to repeat the dose if the pain persisted or returned.

The patient continued to track her headaches in the diary and was seen in the office after three months of following the revised menstrual migraine management plan. She reported fewer migraines associated with her menstrual cycle and noted that they were less severe and shorter in duration. When she repeated the MIDAS test, her score was reduced from 23 to 10. In the subsequent nine months she has reported a consistent decrease in migraine prevalence and now rarely needs the abortive therapy.