Although smoking prevalence among US adults declined by about 42% between 1965 and 2011, this reduction has slowed in recent years. According to 2010 figures from the CDC, 19.3% of US adults (nearly one in five) remain current smokers,1 despite all the evidence of negative effects that tobacco use and smoke exposure exert on good health.2 Each year, 443,000 premature deaths in the US are attributed to cigarette smoking.3

In the face of these discouraging data, and in ongoing efforts to minimize the deadly effects of cigarette smoking, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ program, Healthy People 2020,4 restated its 10-year goals pertaining to tobacco use as put forth in Healthy People 2010.5 These are to reduce the proportion of Americans who currently smoke to 12%, and to increase the proportion of current smokers who have attempted cessation to 80%.4

Though trained to encourage smoking cessation in their patients, health care providers often lack the knowledge, skills, or resources to support patients through the difficulties of discontinuing tobacco use. Whatever barriers clinicians may face in accessing smoking cessation services, the barriers faced by underserved patients are often greater.6 A heightened awareness of these barriers and improved understanding of common smoking cessation methods will help providers better support their patients who are trying to quit.

ASSESSING READINESS AND MOTIVATING PATIENTS

In 2008, the Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, updated its clinical practice guidelines for clinicians who manage tobacco-dependent patients.7 According to evidence from randomized controlled trials, even brief interventions on the health care provider’s part (such as raising the issue of smoking cessation at each patient visit to determine whether the patient is ready to quit) can prompt the patient to seriously consider smoking abstinence.3,8 Being asked repeatedly can advance a patient’s readiness, and any attempts patients make to quit must be robustly supported.9

The Public Health Service’s five A’s3,7 outline the recommended conversation with patients:

Ask about tobacco use;

Advise tobacco users to quit in strong, clear terms;

Assess readiness for tobacco cessation;

Assist in developing a plan to stop tobacco use; and

Arrange a follow-up consultation to review the patient’s success or to reassess cessation readiness.

Whenever a patient expresses any interest in smoking cessation, it is essential for the clinician to respond with motivation. To help the patient prepare to stop, the clinician must address the five R’s7:

Relevance—the importance of smoking cessation to the patient;

Risks of continuing to smoke, particularly health concerns;

Rewards of smoking cessation, especially alleviation of health complaints;

Roadblocks that contribute to the threat of relapse—but which can be overcome with sufficient motivation; and

Repetition of support and reinforcement for this healthy lifestyle choice, be it from family, friends, coworkers, or the clinician. To prepare for times when support seems to wane, patients should be encouraged to phone 1-800-QUITNOW, a number that will connect the caller to his or her state’s quit line.

Repetition may also imply repeated cessation attempts if the first (or most recent) was unsuccessful. According to findings from a literature review, the reasons smokers relapse are numerous, including cravings (the most common) and withdrawal symptoms, weight gain, stress, and exposure to other smokers.10,11 Interventions based on patients’ given reasons for relapse have no apparent impact on the rate of return to smoking.12 Nevertheless, clinicians must take responsibility to motivate patients and reinforce their successes at every encounter.

UNAIDED CESSATION

In a culture demanding quick results and in the context of ongoing pharmaceutical advertisements and aisles lined with quit-smoking products, it may be easy to dismiss unaided cessation. Options range from gradual cutting down to the abrupt discontinuation of tobacco—going cold turkey. Although little research has been devoted to these strategies,13 unaided cessation is the method patients most often cite in their attempts to quit—and the method successful quitters report as most effective.14,15 The patients most likely to succeed at quitting are those who do not ask for help.

ASSISTED CESSATION

Patients with a significant dependence on nicotine are likely to request assistance with cessation.15 Identifying those who struggle to quit smoking and offering appropriate support may represent the difference between their success and failure.9

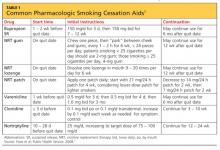

Several available tools to support patients’ “quit smoking” efforts, including pharmacologic options (see table7), are described here.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is used to reduce nicotine withdrawal symptoms by replacing smoking-produced nicotine with an alternate source of delivery. NRT is currently available in several forms: a transdermal patch, gum, lozenge, or the electronic cigarette. The chance of successful quitting is increased 50% to 70% when NRT is used, compared with patients using placebo.16 While the various forms of NRT share the same goal, they are not equally effective.17